By GARY DELSOHN

A graduate student in the Public Affairs

Reporting Program at Sangamon State

University, Delsohn edited a weekly

newspaper in Colorado, the Del None

Prospector, after graduating from Southern

Illinois University with a bachelor's degree

in journalism.

Hammering out a new Illinois law

Capital punishment

'Few issues stir public

passions and individual

soul-searching as much

as capital punishment."

In their rush to revive

the death penalty, Illinois

lawmakers are reacting to

public opinion and facing

limitations from the courts

and a vocal opposition

'Few issues stir public

passions and individual

soul-searching as much

as capital punishment."

In their rush to revive

the death penalty, Illinois

lawmakers are reacting to

public opinion and facing

limitations from the courts

and a vocal opposition

|

THE LAST state execution in Illinois

took place August 24, 1962 when cop

killer James Duke was electrocuted in

the basement of the Cook County Jail.

The deep and abiding doubts about the

morality of capital punishment can be

seen in the recent statement of Warden

Jack Johnson, the man who pulled the

switch in Duke's electrocution. Johnson

said, "I had a definite feeling it was

wrong. There was a feeling of guilt. But I

rationalized it. I said, 'Okay, society,

this is what you wanted and I gave it to

you. It must be right."'

|

Illinois Administrative Director of

Courts Roy O. Gulley, a man who says

he has "no real strong feelings about

capital punishment either way," witnessed an execution when, as a young

man fresh out of law school in 1951 he

was chosen by the late Gov. Adlai E.

Stevenson to be one of the six state

witnesses required by law. "I stood there

in complete terror, with my eyes closed,"

Gulley said. "I went away thinking it

was unbelievably cruel." Opponents of

capital punishment claim those in favor

of it would feel differently if forced to

witness the grisly spectacle of a human

being convulsing in an electric chair as

waves of electricity pulsed through the

body, burning the life away. Rep. Anne

Wilier (D., LaGrange), realizing this

reluctance to witness execution, offered

an amendment to a proposed death

penalty bill (House Bill 3204) which

nearly passed during the closing moments of the veto session of the 79th

General Assembly. Willer's amendment

would have required state witnesses to

executions to be drawn by lottery from

the legislature. The amendment failed

miserably.

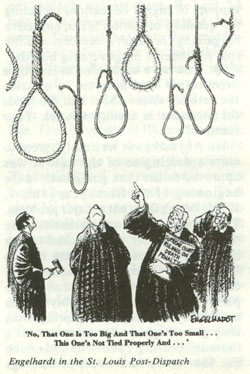

Few issues stir public passions and

individual soul-searching as much as

capital punishment. Legislative debate

and public hearings sometimes become

forums for scriptural exhortations, libertarian denunciations, legal analyses

and a variety of emotional outbursts.

There is no doubt, however, that the

public, like its lawmakers, is firmly in

favor of the death penalty as the best

way to deal with murderers. Yet, vocal

opponents claim murder by the state is

no less perverse or senseless than

murder by individuals. With last summer's U.S. Supreme Court ruling

(Gregg v. Georgia) upholding capital

punishment within certain strict

guidelines, Illinois, like the rest of the

states, is rushing to revive the death

penalty. The sensationally publicized

case of Utah killer Gary Gilmore,

illustrating that state's reluctance to

carry out the ruling it imposed, brought

the issue to the forefront of public

attention. Yet, there are profound and

persistent questions in the capital punishment debate that have gone unanswered for centuries as civilized societies

have sought ways to protect themselves

and punish criminals. Against this

backdrop, it is only a matter of time

before an Illinois governor signs the

death penalty into law.

"The clamor is there," cried Rep.

Roscoe Cunningham, (R., Lawrenceville), "for us to pass capital punishment. Public opinion is behind us on

this. We are in a strong box." Cunningham's remarks, made during a hearing

of the House Judiciary II Committee

last session, underscore lawmakers'

intentions to bring the death penalty

back to Illinois. Our state's last capital

punishment law was ruled unconstitutional by the Illinois Supreme Court in

November 1975 in People v. Cunningham on the grounds that creation of a

three-judge review panel called for in the

law was an improper usurpation of the

powers of the judicial branch of state

government. By creating the "court,"

the legislature overstepped its authority,

the Supreme Court ruled.

March 1977 / Illinois Issue / 3

'There will be few executions; we all know that. But somebody's going to have to pay for murder with his life to set an example'

Although even the staunchest proponents admit they cannot empirically

prove that capital punishment is a

deterrent to murder, or that it accomplishes anything more than quenching

society's thirst for revenge, Illinois

lawmakers, with the support of their

constituencies, are determined to pass a

capital punishment measure. House

Judiciary Chairman Harold Katz, (D.,

Glencoe), is fighting a losing battle when

he says, "The clamor is not enough. If

we react to clamor so will the judges."

Although one might imagine the death

penalty to be one issue where politics

would defer to considerations of justice,

deterrence, and morality, the fact that

"the people of Illinois have spoken" is

paramount, claims death bill sponsor

Roman J. Kosinski (D., Chicago). In

fact, Kosinski and others realize there is

quite a bit of political stock to be gained

in sponsoring and supporting death

penalty legislation. "We got 67 co-sponsors on this thing without even

trying," he said.

Kosinski was the primary sponsor

and force behind a measure calling for

restoration of capital punishment that

passed the House during the veto

session last fall. The bill passed by an

overwhelming 122-45 vote in the House

but stalled in the Senate when its Rules

Committee refused to consider the bill

on an emergency basis. For the 80th

General Assembly, Kosinski has filed

House Bill 10,* almost identical to his

last effort. His primary co-sponsor on

the failed bill was George E. Sangmeister (D., Mokena), now senator,

who said he will introduce a companion

bill in the Senate. Kosinski said, "We

will be going at this thing from both

sides next time. It will be my number

one priority." Hardly anyone thinks

such a measure will fail to be passed and

signed by Gov. James Thompson this

session.

Illinois' 'defendant oriented bill'

Kosinski's bills were modeled after

the statute upheld July 2, 1976, in the

U.S. Supreme Court's Gregg v. Georgia

ruling. The statute calls for a mandatory

death sentence for certain categories of

murder, provided none of a list of

mitigating circumstances are determined to have been present at the time

of the offense. Because, as Kosinski has

said, "Ours is a defendant-oriented bill," defendants can bypass traditional rules

of evidence and introduce any information pertinent to consideration of the

death sentence. H.B. 10 calls for death

for murdering a policeman, fireman,

judge or state's attorney who was on

duty, personnel of the Department of

Corrections, or persons inside correctional facilities with the knowledge of

officials — this presumably would

include visitors and hostages in prisoner

uprisings. Also included are murders

committed in the act of arson, rape,

burglary, indecent liberties with a child

and hijackings. Persons convicted of

multiple murders would also be subject

to execution, as would persons who

murdered on "contract" and persons

convicted of murder taking place in

public places and endangering the lives

of others.

To satisfy the U.S. Supreme Court's

ruling in Gregg v. Georgia, the presence

of one or more mitigating factors would

preclude the death penalty. In its

famous Furman v. Georgia decision of

1972, the Supreme Court invalidated all

existing capital punishment statutes on

grounds they were indiscriminate and

failed to consider mitigating circumstances. Under Kosinski's bill it would

be the defendant's responsibility to

claim such circumstances and the

burden of proof would be on the state to

show, "beyond a reasonable doubt,"

that no such factors existed. The same

standard of proof would apply to the

state's responsibility to show the presence of one or more of the aggravating

circumstances, that is, one or more of

the types of murders listed above.

A defendant convicted of murder but

spared, due to mitigating circumstances,

would be sentenced to an indeterminate

term of not less than 14 years in a state

prison. The mitigating factors in Kosinski's bill that would void the death

penalty are: (1) a defendant found to have no prior criminal background or

record; (2) a defendant under age 18

at the time of the offense; (3) a defendant

"under extreme mental or emotional

disturbance," although not such as to

constitute a defense to prosecution; (4) a

defendant whose victim was a participant in the criminal act; (5) a defendant

acting under threat of death or great

bodily harm; and (6) a defendant not

present at the commission of the murder, except in contract murders. Discussing the third situation of emotional disturbance, Sangmeister admitted in committee that "I don't like

this, it will lead to all kinds of horrendous trials with psychiatrists, but we

kept it in as a result of testimony we

received in our subcommittee hearings."

A six-year moratorium on executions?

Any death penalty bill, in addition to

the expected questions involving purpose and morality, falls prey to criticism

for the seemingly arbitrary selection of

aggravating and mitigating circumstances it includes, and opponents

usually hammer away at these decisions

in public hearings. Opponents of capital

punishment say: "What makes the life of

a policeman or fireman worth any more

than the life of another individual? If we

are asking for execution for murdering

state's attorneys and judges, then what

about the witnesses? They need protection at least as much." Rep. Robert E,

Mann (D., Chicago) alluding to these

questions, asked, "What is the rush to

put the state back in the business of

killing?" He suggested a six-year moratorium on executions until such time

that these problems can be worked out,

Proponents answer by pointing to the 15

years since the last Illinois execution

and cite the tremendous amount of

work and time that went into Kosinski's

bill. Three public and well publicized

subcommittee hearings last summer in

4 / March 1977 / Illinois Issues

Wheaton, Joliet and Chicago produced

reams of testimony, and supporters

questioned the need to procrastinate

any longer. A few days after the veto

session ended, Mann said he would

introduce a resolution this session

calling for a joint committee "to produce a nonpolitical examination, which

could hear persons from both sides of

the issue, in a non-emotional, deliberative fashion." Regardless of the fate of

Mann's proposal or eventual findings or

recommendations of such a committee,

he said, "The chances are very good that

we are going to get a death' penalty law

very soon."

There are some alternatives to imposing a death penalty. Some opponents point to a recently released report

by a Judiciary II Subcommittee on

Adult Corrections, chaired by Rep. L.

Michael Getty (D., Dolton). The subcommittee's recommendation for "flat-time," or determinate sentencing, would

shift the emphasis of incarceration from

the present idea of rehabilitation to

punishment. (See Illinois Issues series

on these proposals, Jan.-March, 1976).

Although it would still be a goal of the

corrections system to rehabilitate prisoners who wish to be, the subcommittee

called the present system of varied

sentences, "Capricious ... an obstacle

to rehabilitation . . . without significant

results." The idea of mandatory life

imprisonment for murder conviction is

also discussed, although capital punishment advocates ask what will then

prevent a prisoner "with nothing to

lose" from killing guards or other

inmates. Cedric Russell, a spokesman

for the Illinois Coalition against the

Death Penalty, said lawmakers want the

death penalty because they lack answers

or solutions to the complex problems of

crime in society. Russell told a Springfield press conference last November

that the death penalty is discriminatory

and implies not justice, but "just-us."

One lawmaker who said he favors the

death penalty voted against it and said,

"It might lull people into believing that

we're making things all right. It takes

attention from the social problems that

lead to murder."

Dual trial system for capital cases

The legislation that eventually becomes law will most likely employ a

"bifurcated" or dual trial system,

whereby one jury determines innocence

or guilt and another convenes to consider the applicability of the death

sentence. A unanimous recommendation of death would be necessary from

the jury for the judge to sentence the

defendant to death. The judge would

review the entire proceeding and decide

whether to honor the jury's recommendation. The House staff member who

drafted the bill said it has not yet been

determined whether the judge can

ignore the jury's recommendation of

mercy and sentence the defendant to

death. In a further effort to meet the

Supreme Court's standards as they

apply to reviewing procedures, all death

penalty convictions would automatically go to the Illinois Supreme Court for

review. Any death sentence found to be

improper would lead to an indeterminate sentence of not less than 14 years. Of

course, neither Kosinski's bill nor any

other introduced would be retroactive,

but would apply only to defendants

sentenced to death after the law took

effect.

|

Although the U.S. Supreme Court

has sanctioned capital punishment, the

picture is becoming increasingly muddled as events develop. The U.S. high

court recently overturned the capital

conviction of a Georgia man on the

grounds that a potential juror was

eliminated because he expressed reservations about capital punishment.

Because many persons share such

reservations, the court said, elimination

of a potential juror without sufficient

questioning to determine if those reservations would prejudice him or her in

the case would lead to overturned

convictions. An interesting sidelight to

that ruling is Cook County State's Atty.

Bernard Carey's opposition to capital

punishment. Carey, who is the number

one legal officer in a county that has as

much violent crime as any in the nation,

opposes capital punishment because

juries are so reluctant to recommend it

that the legal system is "corroded" by it,

according to Rep. Katz. Thus, capital

punishment is a legal quicksand for the

courts and lawmakers.

Statistics can be found to buttress

almost any argument for or against

capital punishment, and even the U.S.

Supreme Court has called the case for

and against deterrence "simply inconclusive." Despite this and the myriad

moral and religious considerations of

the issue, legislators are reacting to what

they perceive to be a "clamor for capital punishment."

Gov. Thompson has said he will sign

death penalty legislation meeting the

Supreme Court's standards. In his

position paper on criminal justice,

however, Thompson said, "If punishment does not swiftly follow an offense

its impact is diminished. The deterrent

value of a criminal penalty depends

upon swift and certain adjudication."

The absolute finality of capital punishment makes mistakes irreparable, and

the slowness of the legal system in such

cases detracts from the force of any

potential deterrent value. In fact,

because the Illinois Constitution mandates a Supreme Court review of all

death sentences (Article VI, section 4b),

speedy disposition of such cases is

impossible.

|

|

The larger questions of deterrence

and rehabilitation behind capital punishment will not be answered when a bill

is signed into law to revive executions of

the most vicious criminals. For the law

to have even the slightest trace of

deterrence, it must be enforced. The

Gilmore case in Utah has shown the

reluctance to carry out what capital

punishment laws mandate — state

executions. Perhaps underlining this

reluctance is Sangmeister's comment,

"I'm not eager to see anyone strapped

into a chair and have the life burned out

of him. I'm not a sadist. There will be

few executions; we all know that. But

somebody's going to have to pay for

murder with his life to set an example."

March 1977 / Illinois Issues / 5

'Few issues stir public

passions and individual

soul-searching as much

as capital punishment."

In their rush to revive

the death penalty, Illinois

lawmakers are reacting to

public opinion and facing

limitations from the courts

and a vocal opposition

'Few issues stir public

passions and individual

soul-searching as much

as capital punishment."

In their rush to revive

the death penalty, Illinois

lawmakers are reacting to

public opinion and facing

limitations from the courts

and a vocal opposition