The School Board's fight to keep federal funds

|

The School Board's fight to keep federal funds Chicago's 4-ring circus |

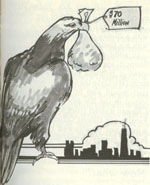

UNTIL it surprised everyone by coming up with a plan to end teacher segregation, the Chicago School Board was on the verge of losing more than $70 million in federal funds by September. The potential loss was due to major violations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as well as violations of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

On May 25 the Chicago Board of Education announced a plan for staff desegregation that will, if accepted and implemented, prevent the cutoff of the crucial federal money. By a 10-1 vote the Board agreed to transfer 2,212 teachers and 80 principals in a new staff integration plan. The plan specifies 1,686 regularly assigned teachers and 526 full-time substitutes will be moved by September 1977. Each school will achieve a racial balance from 35 to 60 per cent minority teachers. Transfers will be made on the basis of seniority, using a computer to match white and minority teachers in each grade and subject. A spokesman for the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) said he will recommend that the plan be accepted. Robert Healey, President of the Chicago Teachers Union commented, "It's acceptable because you have no choice."

The proposed plan is the result of a series of battles dating back to 1965 between OCR, the Chicago Board of Education, the Illinois Office of Education and the Chicago Teachers Union. The issue has been desegregation, and the controversies have resulted in threatened and sometimes actual withdrawal of federal funds from Chicago schools. Involved are the 25,868 teachers employed by the school district and some 524,221 students, whose education has not been enhanced by the dispute and who will certainly be affected by future skirmishes.

What is the background on the long struggle over teacher desegregation? What role did the various parties play? These are important questions, not only in understanding how the proposed plan for teachers finally came about but in looking to the future. The root of the problem is segregated schools. Only a small fraction of Chicago's public schools are racially balanced, and, as of this date, the School Board has announced no plans for further desegregation. More controversy and more bitterness can be expected unless the parties involved have learned from the struggles they have already been through. The causes of the dispute reach back to the early sixties and, ultimately, to the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 desegregation ruling (Brown v. Topeka Board of Education).

Illinois, like other states, provides programs and services which are parlor in whole under contracts administered by the Division of Equal Educational Opportunities of the U.S. Office of Education. This division derives its authority from the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It is the state, however, which must take on the task of desegregating the schools. The Chicago School Board must meet state as well as federal standards,

Chronology of controversy

September 1961: Alleged violations

of the Fourteenth Amendment were

brought by a group of parents (Webb v.

Board of Education of the City of

Chicago) who believed that Chicago schools were segregated. There was an

out-of-court settlement after the Chicago School Board agreed that a panel

of five experts, chaired by Philip Hauser

would conduct a study of the Chicago

schools to decide if they were segregated.

November 1961: Because there were so many grievances concerning the Chicago School Board, the Board authorized another survey, this time to examine the quality of public education in the city of Chicago. The Havighurst Survey (named after its chairman, Robert Havighurst) did not specifically explore the segregation question of the Chicago schools. The panel was concerned with the question of whether there was quality education in the Chicago schools, while the earlier Hauser Study concentrated on the question of segregation.

March 1964: The Hauser Study found the schools to be segregated. The quality of education in black schools was inferior to that in white segregated schools. Between April and November 1964, the Board adopted the Hauser Study "in principle." It also opened enrollment for all its trade and vocational schools on a citywide basis. It issued statements such as "we will continue to be guided by, and comply with, state and federal laws in the spirit of the 1954 Supreme Court decision on desegregation."

November 1964: The Havighurst Survey was submitted to the Board. It contained 22 major recommendations; several of them dealt with the problem of desegregation.

May 1965: In a public statement, Chairman Havighurst stated that no major commitments had been made on the major recommendations of his report.

July 1965: The Coordinating Council of Community Organizations of Chicago

July 1977 / Illinois Issues / 13

(CCCO) filed a complaint with the U.S. Office of Education which ultimately led to an investigation of Chicago schools by the U.S. Department of Justice. This complaint marked the beginning of the Chicago School Board's problems with the federal government over alleged segregation in the schools.

August 1965: HEW appointed a team to study the question of segregation of the Chicago schools to see if they were in violation of Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act.

October 1965: The Chicago School Board and HEW reached an agreement which reinstated federal funds which had been suspended in September 1965. The Chicago School Board promised there would be no discriminatory practices in apprenticeship programs at either the city's trade or vocational schools.

January 1967: A report from the U.S. Office of Education, entitled "Report on Office of Public Education Analysis of Certain Aspects of Chicago Public Schools under Title VI of Civil Rights Act of 1964" was issued. This report identified serious violations of the law in the following areas:

August 1967: A report issued by Dr. James Redmond, Chicago school superintendent, was adopted by the School Board. This report, known as the Redmond Plan, recognized that there were schools which teachers tend to leave. The plan mandated the same percentage of certified teachers for each school. Teachers would be allowed to request a transfer for integration purposes.

October 1967: The U.S. Commissioner of Education requested time lines for implementation of the Redmond Plan. He further demanded the right to review the development of the plan to make sure it was in compliance with Title VI.

July 1969: The Department of Justice sent a letter to the Board regarding their faculty assignment and transfer policies. The Redmond Plan was criticized for being more of a prospective plan than one which addressed the present problems. The Board responded by outlining a new plan changing the pattern of faculty assignment and transfer policies. It issued a three-phase equalization plan stressing faculty desegregation, equalization of faculties and the assignment of substitute teachers.

October 20, 1969: The Department of Justice rejected the School Board's plans and suggested the Board cooperate with HEW.

November 25, 1969: The School Board requested assistance. The Office of Education appointed an outside panel of consultants to establish a feasible faculty desegregation plan.

June 30, 1970: The Office of Education sent a report to the School Board with the following recommendations: "assign, reassign and exchange the teachers of one race with the teachers of another race in all schools and the instructional units of the Chicago Public Schools where the percentage of white and black teachers differs from the present system-wide percentages by more than ten percent." The report also noted that 93 per cent of all school principals were white. The Chicago Board of Education did not accept all of these recommendations and, consequently, did not meet the requirements of the Justice Department.

March 1972: The Justice Department

rejected yet another School Board plan

entitled "Chicago Board of Education

Plan to Integrate School Faculties and

Equalize Per Pupil Costs." This plan,

adopted by the Board in 1971, was

ratified by the Chicago Teachers Union.

However, the Department of Justice

stated in its rejection letter that "it is our

view that the plan adopted by the Board

is not in conformity with the requirements of federal law regarding school

desegregation. Nor does it appear the

plan promises to achieve compliance

with the law in the future."

The Chicago Board did not agree that

its plan was not in compliance with the

requirements of federal laws and sent

questions to the Justice Department

rebutting the plan's rejection. The

Justice Department answered each

question and requested a final plan. The

Board decided to resubmit the same

plan to the Justice Department saying it

"is the best thinking of this Board. This

is our plan."

June 1973: This action almost cost the Chicago schools $2.3 million. The federal government, however, reconsidered its decision and gave the Chicago Board a second chance. HEW informed Supt. Redmond that the regulations for faculty integration were being rewritten. Redmond believed the school system would qualify for funds under the new relaxed guidelines. The key revision in the guidelines was to make school districts eligible if they had a "promising plan" to end faculty segregation. Because of the new guidelines, funds which had been cut off June 12 were reinstated and were received by mid-August.

October 1975: HEW's OCR formally

charged the Chicago School Board with

practicing racial discrimination in the

assignment of teachers and the Board

had 60 days to submit an acceptable

plan for faculty integration (to be

implemented in September 1976). The

Board asked for and received a 60-day

extension to determine what it would do.

OCR's action of October 1975 resulted from its final rejection of the 1971

Faculty Integration Plan, which the

Board and Union had been working on

for years. OCR held that the Board of

Education consciously discriminated in

the assignment of faculty in both

secondary and elementary schools.

Faculty members were assigned to

schools, OCR said, on a racial basis,

blacks to black schools and whites to

white schools. OCR also charged that

minority group students had a higher

percentage of teachers with less than one

year experience than white students,

and that white schools had a higher

percentage of teachers with 13 or more

years experience. Furthermore, black

schools had fewer teachers with advanced degrees and regular certificates.

Finally, OCR said that the Board had

failed to provide students who spoke a

language other than English with

educational services which allowed

them to equally participate in the

schools' instructional program.

February 1976: By referendum, Chicago teachers approved a plan to increase faculty integration. Written with the cooperation of the Board, it included provisions to:

• establish a 70 to 30 per cent reversible ratio of minority to non-minority teachers instead of the 75 to 25

14 / July 1977 / Illinois Issues

• assign new teachers so as to enhance integration, reassign some experienced teachers for the same reason. Both the Board and Union believed that the 70 to 30 per cent goal would not make a school identifiable as a white or black school.

In 1971, the Chicago Teachers Union gave up the right of teachers to transfer to another school in order to improve faculty integration in Chicago schools to avoid having buildings that were labeled either all white or all black.

Twelve years after the Hauser Report and four years after the rejection of the 1971 Plan for Integration, the Chicago Board of Education was informed by OCR that this plan "does not provide adequate, timely solutions for the violations which this Office has found to exist in the Chicago School System." OCR would now begin formal hearings on his case.

|

The state's position

|

When Michael J. Bakalis became state superintendent of public education in 1970, the state's first formal desegregation enforcement program was established. School districts were required to report enrollment data and state what steps had been taken in previous years to either eliminate or prevent racial isolation. By 1972-1973, Chicago District 299 was among the districts being cited for non-compliance with state rules. When Joseph M. Cronin became state superintendent in 1975, he continued the desegregation enforcement program.

HEW's position

Since OCR believes that the Chicago

School Board has not complied with the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, it has sought to

cut off all federal funds to the Chicago

schools. This loss of federal funds would

cost the Board somewhere between $70

to $150 million dollars a year, and all

federally funded programs in the Chicago schools would be eliminated. Since

the Chicago School Board's "promising

plan" never materialized, HEW decided

a court hearing was necessary to determine what charges would be brought

against the Board. OCR concluded that

this alternative approach would motivate the Board to submit a plan which

was consistent with the requirements of

Title VI. This case (#S-120) was brought

before Administrative Law Judge Everett Hammarstrom in Minneapolis,

Minn., under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

The Union's position

The Union was not involved in formulating any new plans. However, it

wanted to be kept informed of interaction between the Board and the OCR,

and did not want the board to modify

the plan that the Union approved in

February 1976 "unless a court order

mandates this." The Union has gone to Court to

attempt to protect its members' seniority and civil rights and has filed five different briefs as amicus curiae (friend of the court) to determine if the plan complies with the law. It contends that determining whether a school is black or white by the faculty racial composition

is only one factor in determining whether de jure (by design) segregation has occured. The Union claims that the present racial imbalance is only due to

de facto segregation, that is, it is not a

designated School Board plan. This

type of segregation, it argues, bars

government intervention. "The Union is

committed to the idea that faculty

integration is an idea whose time has

come," says Lester Davis, editor of the

Union newspaper. "We'll have to live

with it; we'll have to achieve it; we'll

have to do it. The question is when, how

long, and by what means." In presenting their legal case. Union

leaders have cited the U.S. Supreme

Court's June 1976 decision of Washington v. Davis which defined de jure and

de facto segregation. Relying on this

decision, the Supreme Court vacated a

decision by the Chicago Court of

Appeals regarding the Indianapolis

schools, U.S. v. Board of School

Commissioners Indianapolis, Indiana; a

decision which involved busing students

across district lines and changing school

districts. The Union has tried to prove

that not one court decision since 1964

has demanded a movement or distribution of experienced teachers. "What the

Union is opposed to," said Davis, "is the

immediate disruption of the schools. If

we get past September 1977, tremendous strides will be made toward

integration." The Union hoped that if

the administrative law judge ruled a

large movement of teachers would be

necessary, it would not take place until

school had begun. No changes in

teacher assignments, therefore, would

Because of the devastating effect the

loss of federal funds could have upon

the Chicago schools, the Union and

Board have worked together to come to

terms with OCR. The Chicago School

Board, of course, is legally responsible

for the education of the children of

Chicago. Yet as a recipient of federal

funds, the Board has a statutory and

contractual agreement with the federal

government. The position of the Teachers Union is much different since it has

not entered into an agreement with the

federal government. It still retains the

legal right to intervene to protect the

civil rights of its teachers.

July 1977 / Illinois Issues / 15

occur before September 1978.

The Board's position

So the Board walked softly, hoping it

could wait just a little longer before it

was forced to make any changes. But

time ran out. The Board had to come up

with a plan, and it did.

The Board does have many factors to

contend with. First, the policy of

neighborhood schools has always been a

Board policy, as Chicago has always

had strong ethnic neighborhoods.

Parents have never wanted their children to go to school outside of their

neighborhood. During the Redmond

years, even many blacks in Chicago

favored keeping their own children in

their own schools with black teachers to

teach them. Secondly, the Board has

had to contend with a strong Teachers

Union. Chicago's teachers do not want

to give up their present positions for new

locations. Furthermore, the Board does

have a contract with the teachers, that if

broken, could result in a strike.

The decision

All evidence on Case S-120 had to be

submitted by January 31, 1977. On that

date, the Administrative Law Judge

Everett Hammarstrom closed the case.

The questions the judge felt he had to

decide were:

• "Is the School District in violation

of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

with regard to practices and policies of

faculty and professional staff assignment?

• "Has the Department [HEW] made

valid efforts or attempts to secure

voluntary compliance? • "If the School District is not

fulfilling its Title VI obligations, and

valid efforts or attempts to secure

voluntary compliance have been made

by the Department, what, if any forms

of federal financial assistance should be terminated?"

On February 15, 1977 Judge Hammarstrom reached his initial decision. He said that the Chicago School District had failed to provide proper instructional programs to its non English-speaking minority students. This was in violation of Lau v. Nicholas (students of Chinese ancestry who did not speak English and received no special lingual services: San Francisco, Calif., 414 U.S. 60 (1974)). The School District, therefore, was also in violation of Title VI and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The School District had failed to identify its national minority students. Non-English-speaking or limited English-speaking students are not able to benefit from the School District's educational programs. This noncompliance involved approximately 31,000 students.

|

Students cannot be separated by race, according to Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483 (1954). "The School District consciously consummated actions with regard to teacher assignment," stated Judge Hammarstrom. "This has resulted in racially identifiable faculties." Therefore, the School District purposely assigned teachers to certain schools on the basis of race. The effect of these policies has been to isolate black teachers and black administrators in some schools and white teachers and white administrators in others. The School District, Hammarstrom decided, is not sending its children to schools where the faculty is racially balanced. |

|

On the basis of the above violations, the Chicago School District was found guilty of violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and of violating the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. However, the School District was not found to be in violation of assigning teachers to different schools according to their teaching ability. There was no violation of the quality of educational services as determined by teaching experience. Therefore, on these two issues, the School District was not in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment or the Civil Rights Act. Judge Hammarstrom allowed either the School District or HEW to appeal his ruling with a 20-day period if either disagreed with his findings.

In addition to the HEW money, all financial assistance given by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to the Chicago School District would also be terminated. HUD joined in the lawsuit since it gives the Chicago district from $4 to $5 million, Finally, the Illinois Office of Education would not be allowed to grant any federal money to the School District until it complies with this order.

Now what?

Once the Reviewing Board reaches a

decision, it notifies all the parties

involved. Within 20 days after the

decision has been reached, either party

may request HEW Secretary Joseph H,

Califano to review the final decision,

The secretary for "special and important

reasons" may grant such a request in

part or in whole. For all practical

purposes, the general practice has been

that the decision of the Reviewing

Board is final. In that case, the secretary

of HEW sends a report to the committees of Congress. Congress has no role in

either reviewing or changing the decision but must be notified. After Congress is notified, federal funds will be terminated after 30 days. According to Al Sumner, project

director at OCR, in order for the

Chicago School Board not to lose any

money it would "have to have a plan

that is likely to work. The plan must

spell out what is right and how the

Board will achieve its goals. If not they

could lose approximately $70 million." According to OCR Attorney Goeser,

"Most important of all, the monies will

be terminated. The amount doesn't

Both the Chicago School Board and

HEW's OCR have appealed Judge

Hammarstrom's decision. Lawyers for

the Chicago School Board and OCR

Attorney James R. Goeser sent their

appeals on March 7 to the Civil Rights

Reviewing Authority, organized under

the Civil Service Commission and

independent of the Justice Department,

This Reviewing Board is composed of

three to five lawyers or law school

professors and is independent of HEW,

The Board usually takes three months to

reach a decision on appeal.

16 / July 1977 / Illinois Issues

matter. What matters is the programs 8 will end. If the Chicago School Board fails to accept an impartial ruling, the only sanction left is to cut off federal funds. It will hurt the school children, and that's not what the department wants." If the Board did not comply, OCR would start civil proceedings.

Davis of the Teachers Union said, "It is our hope that by the time the appeal process ends that we will have achieved a measure of integration that will negate the necessity of any large movement of teachers." If HEW wins its point on the experience factor before the Review Board, "that would merely require a greater number of teachers — you're talking almost double." If the Reviewing Board confirms the administrative law judge's decision, "further movement may be needed but nowhere on the massive scale envisioned in 1971." When asked if the Union would ever consider a strike over this issue, Davis added, "I couldn't categorically say. I think it is very unlikely in light of the statement and the policies that had been established that we were in favor of integration. We'd abide by the law at all times. We'll abide by the final decision of HEW."

Dr. Joseph P. Hannon, Chicago's general superintendent of schools, issued a statement on February 17,1977 which said, in part: "The Chicago Public Schools are not in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution or Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act in regard to the quality of educational services delivered to minority students. The Board is in compliance with regard to the experience factor of teachers. This substantiates the efforts which have been made to provide equal educational opportunity to all of our students in all of our schools. The Board of Education is in continuing negotiation with the U.S. OCR, and the most current negotiations were not a part of the initial decision rendered by the Law Judge."

Now the Board has a plan, but desegregation problems will continue. On Tuesday, April 5,1977, at a meeting of the Illinois Board of Education, Chicago Supt. Hannon made a report that admitted for the first time that only 83 Chicago schools with an enrollment of 66,362 students are racially balanced. This means that only 12.5 per cent of Chicago's public schools are racially balanced.

July 1977 / Illinois Issues / 17