|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

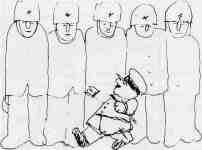

VOLUNTEERS Pushing the Right Buttons by Dianne M. Haycock Ms. Dianne M. Haycock is the Coordinator for the Volunteer Bureau in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada. She is also a member of the Board of Directors, Ontario Association of Volunteer Centers. This article is reprinted from the December 1979 issue of Recreation Canada with permission of Canadian Parks / Recreation Association. "Where do we find volunteers?" How do we motivate them?" Two frequently asked questions prompted by an apparent shortage of volunteers at a time when economic restraint has increased the demand for their services. Recruiting and retaining volunteers has become a major problem for many organizations. Large amounts of time and money are spent by the voluntary sector in attempts to attract local citizens. Despite that, few respond and even fewer stay. It is my belief that today's volunteer market is better than it has ever been. Volunteerism, however, must not compete with a plethora of leisure time activities and societal attitudes which equate value with dollars. To do this (compete), we must abandon traditional recruitment methods which stress organizational needs, and focus instead on the needs of the volunteer. In popular phraseology, we must learn to "push the buttons which turn him on." Although it is generally acknowledged that volunteers require "pay-offs," few of us have analyzed this concept thoroughly or realize its value as a recruitment tool. We still tend to rely on standard appeals to the public and expect annual recognition events to supply the necessary strokes. "Pushing the right buttons" to attract and satisfy volunteers requires an understanding of the basic needs which motivate all human beings: survival, stimulation, security, acceptance, recognition and personal growth. These can be ranked as progressive motivational levels. Each prospective volunteer comes to an organization at a different level and may verbalize his needs quite simply as job experience, use of spare time, etc. An exploratory interview, however, will soon indicate the underlying motivations which must be addressed. Satisfying the needs of each level and providing the stimulus for the next is the combination necessary to ensure a "turned-on" committed volunteer. Meeting organizational needs through this process necessitates examining each volunteer assignment to ascertain which needs it would fill, and designing a recruitment campaign to appeal to an individual at that level. A closer examination of these human needs will soon illustrate their relevance to volunteerism, and demonstrate the mutual advantages of using this system. To best accomplish this, let's follow John Doe through all six stages of his development. SURVIVAL—It is generally accepted that an individual functioning at this level does not volunteer. His time and energy are devoted to providing the necessities of life for himself and his family, thus his concerns are usually self-oriented. STIMULATION—Having reached an acceptable standard of living, John Doe will now consider external activities and may be inclined to approach an organization. (His choice is often prompted by personal circumstance or experience.) John will be hesitant to volunteer feeling 'unqualified' to contribute much. At this stage he needs encouragement and reassurance that even a 'little' means a lot to a voluntary organization. SECURITY—John Doe's need now is to feel secure. Volunteering should pose no threat to him personally or to his current life-style. The task should fall within his capabilities and a manageable time frame (e.g., 2 hours once a week). Staff should be accessible to answer his questions and offer assistance if required. John Doe will soon have second thoughts if the assignment is too difficult, incurs too much responsibility or more time than was initially indicated. (An upset spouse with a disrupted schedule soon puts an end to volunteer activity.) ACCEPTATANCE—When John is comfortable with his task, his interest in the organization will expand. It becomes important for him to know that both he and his work are accepted parts of the overall scheme. In order to push the right buttons at this motivational level, John should be given the opportunity to socialize with other volunteers and encouraged to contribute suggestions and comments about his assignment. Rejection by established cliques or a sense that his position is inferior will easily discourage him. See Buttons ... Page 11 Illinois Parks and Recreation 8 July/August, 1980 Buttons . . . From Page 8 RECOGNITION— Once accepted, Mr. Doe will expect a measure of respect and recognition of his abilities and efforts. This can be achieved not only at an annual recognition event but also through on-going praise, encouragement and constructive performance appraisal. Increasing his responsibilities is also an acknowledgment of abilities. Status, which is part of recognition, may be met by committee chairmanships, initiation to the Executive or a more public volunteer assignment. If John feels his work is not appreciated, or has outgrown his initial task, he will move on to greener pastures. Offering training courses is another indicator to John that he is valuable to the organization. PERSONAL GROWTH— John's leadership abilities are now becoming evident. He is eager to learn new skills, expand upon old ones and anxious to play a greater role in policy development. His time and energy commitment have greatly increased demonstrated by his willingness to accept more responsibility and challenging tasks. To sustain John at this level and ensure his commitment, he must be offered those challenges and responsibilities through upward mobility in the organizational heirarchy and tasks designed to utilize his leadership skills. (Past-Presidents often peter-out because these are not offered.) Recognizing these needs does not require a degree in psychology. Simple perception and an ability to communicate will enable any co-ordinator of volunteers to push the buttons which turn on volunteers and organization alike. RECRUITMENT Using this knowledge of motivational levels as a recruitment tool demands a close scrutiny of all volunteer tasks within the organization (current and proposed). An explicit, honest job description outlining all aspects of the task should be developed. It is essential to include time requirements, who and what the volunteer is responsible for, and whom he is accountable to. Necessary qualifications should be spelled out to avoid disillusionment and resentment on either side later. Using this document, the recruiter can develop a profile of the volunteer needed to fill the assignment. Necessary mechanical skills and time required will be evident and listing the benefits to be gained by the volunteer will indicate both the level the task will appeal to, and the motivational level the volunteer must have already reached to be capable of handling it. With a definitive statement of the task and a clear picture of the individual needs, recruitment strategies can now be designed. A committee is worth its weight in gold at this stage. Brainstorming will soon produce many possible sources and perhaps even personal contacts. A Volunteer Bureau is also a valuable resource. If resorting to media advertising, design the material as though for the Help Wanted column. Specific appeals are more fruitful than general requests especially when the benefits to the volunteers are clearly stated. Recruitment pamphlets should be treated in a similar manner listing tasks, requirements, benefits. In short, appeals to the public should be directed to a specific target group who can easily identify with the request and relate to the benefits. Personal contacts are the best proven method of recruitment, and are much easier to make when job description and volunteer profile have been developed. Defining both expectations and requirements permits the prospective volunteer to formulate a sounder decision than one produced by emotional appeal or induced guilt. Those who do turn down the task won't feel forced to fake excuses, will offer valid reasons for doing so and will be more receptive to future approaches. Training has been mentioned earlier in this article and I feel it is important to stress that no matter what motivational level a volunteer has reached, training will address many of his needs. Initially it will stimulate his interests and make him comfortable in his task. It makes the volunteer feel accepted, recognizes his worth to the organization and develops his leadership skills. Training volunteers is an investment in the future of your organization. Obviously the six basic needs of humans manifest themselves in many forms both verbal and physical. However, with a knowledge of these, and practice in applying motivational techniques based on those described above, the co-ordinator of volunteers will soon become adept at recognizing which buttons need to be pushed. The benefits of this system are many-fold. Satisfied volunteers will themselves recruit others and be the most effective Public Relations device possible. Their commitment will build more effective voluntary programs and strengthen organizational structure through creative contributions at all levels. Recruitment strategies are easily formulated to appeal to homemakers, students, seniors or other target groups and will greatly facilitate the interviewing and screening process. Pushing the right buttons through matching volunteers and organizational needs will ensure the organization operates at maximum potential with a full volunteer complement. The question of "Where do we find volunteers" will never arise. Illinois Parks and Recreation 11 July/August, 1980 |

|

|