|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JAMES KROHE JR.

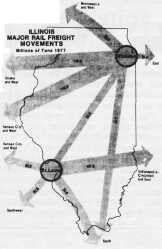

Transportation and the new economics of oil On the highways and on the farms, gasoline consumption is down in Illinois. Like the rest of the nation, the state is weaning itself of dependence on foreign oil. But the decrease has affected state tax increases and forced the shutdown of refineries and car assembly plants. These and other effects of the new economics of oil are explored in part one of Jim Krohe's two-part article. Next month he will analyze state intervention in the transportation marketplace MOVING things is one of the jobs Illinois does best. The state is the site of O'Hare International, the world's busiest airport. It boasts a river system in the Illinois whose annual cargoes of 100 million tons are second only to the Mississippi's. It is served by the nation's two largest rail gateways in Chicago and St. Louis. And the Dan Ryan Expressway in Chicago has been called the world's busiest highway — an

All that movement takes a great deal of energy. According to the Illinois Institute of Natural Resources (IINR), 23 percent of all the energy consumed in Illinois in 1978 was used for transportation. Of the residential, commercial, agricultural and industrial sectors of the state economy, only industry used more energy than transportation. Measured in Btus, consumption for transportation in 1978 was 961.2 trillion, nearly twice that consumed in 1960. Virtually all this energy is in liquid form. Motor and aviation gasoline, jet fuel (kerosene and naptha), diesel fuel and distillate fuel oil added up to 175.7 million barrels of petroleum in 1978, which was 98.5 percent of all the energy used for transportation that year. Illinois sails on a sea of oil, or more specifically, gasoline. In 1979, Illinois' 7.5 million automobiles drove more than 90 percent of the passenger-miles traveled in the state; of the transportation energy used in Illinois, motor gasoline alone accounts for roughly 80 percent. Consumption down Illinois in the late 1970s was producing about 26 million barrels of oil per year. This amounts to less than 10 percent of the state's annual consumption. Illinois thus stands in the same relation to the rest of the U.S. as the U.S. does to the world: Both are net importers of petroleum and net exporters of dollars. The difference is that while the U.S. currently imports only about 42 percent of its oil, Illinois imports 90 percent. (Most of the crude oil delivered to Illinois refineries comes via pipeline from Texas and off-shore Louisiana fields. Illinois also is connected via product pipelines to Gulf Coast refineries which furnish the state with finished fuels.) And since not only the state's transportation but also its agriculture runs almost entirely on oil, as well as 40 percent of its commerce, vital segments of the state economy are vulnerable to price increases and supply interruptions from beyond its borders. It thus must be considered encouraging news that Illinoisans appear to be weaning themselves of "foreign" oil. Figures compiled by the IINR reveal that total gasoline consumption in Illinois in 1980 was 4.8 billion gallons. That was 13 percent fewer gallons than were consumed in 1978, even though the number of miles traveled remained virtually unchanged at approximately 65 billion. (These savings roughly parallel national figures, which show a decline in gasoline consumption of 16.5 percent in the two years beginning in March 1979.) IINR officials credit the reduction to increases in gasoline prices, which averaged 34 percent

24 | September 1981 | Illinois Issues

higher in Illinois in 1980 than in 1978. Similar economies have been achieved in agriculture, where consumption dropped by 24 percent between 1975 and 1978 even though the number of acres farmed remained stable. Small car sales up Simple efficiencies such as tune-ups, car-pooling and improved driving habits played a part in achieving these savings. But the biggest cause of this happy effect is a switch to smaller, more gas-efficient cars. Sales figures compiled by the Illinois New Car and Trucker Dealers Association show that, compared to 1979, 1980 sales of small foreign cars in the state increased by roughly 6 percent while sales of larger American cars dropped by about 30 percent. (Sales figures were by make, not model type; if sales of American-made small cars such as the Chevrolet Chevette were included, the disparity between small and large cars would be even greater.) And further economies are possible; although the Illinois secretary of state reports that the share of smaller cars (35 horsepower or less — a VW Rabbit has 20 horsepower) among registered cars in Illinois has grown

Transportation affects all industry in Illinois, and energy affects transportation. What can't be moved can't be sold, and what can't be moved cheaply can't be sold at a profit. But, as noted, transportation in Illinois is also an industry in itself, one which employs an estimated 250,000 people. That industry is being transformed by the new economics of oil. According to the U.S. Census, for example, costs of petroleum wholesalers have generally risen faster than prices, with the result that the number of bulk oil distributors in the Chicago area alone has dropped by more than 42 percent between 1972 and 1977. Thinner profit margins, plus pressure by big oil companies to funnel their products through company-owned outlets, has led to similar reductions in the number of gas stations in the state. In 1979 there were 14 oil refineries operating in Illinois; largely because of declining demand for gasoline, both the Amoco and Texaco oil companies announced this spring that they would close refineries operating in Illinois since 1903 and 1911 respectively. Finally, the consumer shift to smaller cars left a major Illinois industry ailing; poor sales threatened to force a shutdown of Chrysler's Belvi-dere assembly plant, which would have put an estimated 34,000 Illinoisans out of work. Tax receipts affected Any enterprise so basic also affects government. For example, the state and local governments are themselves sizable consumers of energy for transportation, the rising costs of which have unbalanced budgets across the, state. Municipalities have switched to smaller fleet cars, reduced police patrols and converted gasoline fire trucks to diesel. According to the Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs, which held a series of nine workshops for local governments on such once-arcane topics as fuel management, such steps have reduced some cities' fuel consumption by as much as 100,000 gallons a year. The State of Illinois used roughly 8 million gallons of motor fuel in an average year in the late 1970s, and consequently has been driven to similar economies. In 1979, Gov. James R. Thompson ordered that the state's vehicle fleet switch to gasohol, the 90 percent gasoline-10 percent ethanol blend. Although the conversion was intended in part as a promotion for the

September 1981 | Illinois Issues | 25

to the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT). The structure of the state's road financing system has thus placed the state in a philosophical as well as a financial quandary. As long as road revenues remain a function of consumption, the state has a vested interest in energy waste. "Fifty is Thrifty" only for the motorist. For IDOT it is a disaster. Increased production sought Just as Illinois resembles the U.S. as a whole in its use of energy for transportation, so is it alike in its official thinking on the subject. The policies of Washington and Springfield are virtually identical in their broader aspects. Leaders in both capitals officially hold conservation to be good, but prefer to trust to market mechanisms as the agent of conservation. Both stress energy independence, and seek to achieve it by increased domestic production of energy, especially liquid fuels — efforts, however, which are based on technical and economic assumptions which have yet to be proven trustworthy. For example, in late 1980 IDOT published its "Illinois Transportation Plan: Principles and Investment Strategies." It is not really a plan, in spite of its title. But the document does present "fundamental principles that will guide the investment of State funds in transportation projects." As reflected in the IDOT summary, transportation strategy is more a matter of means than ends. Naturally, the top priority is to operate and maintain the present auto-dominated system which, along with oil imports and traffic jams, is the legacy of the cheap energy era. Expansion of that system is suggested as a possibility if funds are available; rather than try to turn a sow's ear into a silk purse, in other words, IDOT aims merely to make a bigger and better sow's ear. The report does acknowledge that it is the "joint responsibility of the government and the private transportation sector to consider the energy implications of investments." But IDOT makes clear that it is "the responsibility of the general public . . . to voluntarily conserve energy through the wise use of available transportation facilities." Energy conservation in Illinois, then, is a private, not a public concern. Consequently the state's own efforts to encourage conservation in the private sector (nearly all of which, reveal-ingly, have been funded by Washington) have been feeble. The IINR, as the state's energy agency, manages a program to recover and recycle used motor oil, offers demonstation projects to encourage reduced tillage by farmers and briefly sponsored a bicycle commuter program. Its most significant success is a ride-sharing /van-pooling program in which riders are matched using computers. To date the program has put perhaps 150 van pools on the road which carry an estimated 1,500 commuters every day. IINR officials estimate the resulting energy savings to be 1.86 trillion Btus — less than 0.002 percent of the state's annual transportation energy expenditure. Illinois wells depleted The most effective conservation incentive yet discovered is price. Yet the State of Illinois, like the federal government, has so far refused to enact a conservation tax on motor fuels. Even deregulated gasoline in the U.S. remains as much as $2.00 per gallon cheaper than gasoline in such European nations as Italy, Great Britain, France and West Germany where (not coincidentally) per capita consumption is much less. A large part of the differ ence (in Italy's case $1.83 more per gal' Ion) is the punitive taxes levied on gasoline by European governments to stem demand to minimize devastating oil import bills. A tax of similar magnitude levied in Illinois in 1980 would have earned the state roughly $8.75 billion; even allowing for reductions in demand occasioned by such a drastic price jump at the pump, revenue would still exceed $6.5 billion. As Robert Whitford of Purdue University told the eighth annual Illinois Energy Conference of the University of Illinois' Energy Research Center in Chicago

26 | September 1981 | Illinois Issues

last year, "Europeans, by keeping the price of gasoline at an artificially high level, have not only created tax revenues but ... forced the design of waller, more fuel efficient automobiles, developed good mass transit systems, built highly integrated urban areas, and encouraged relatively less automobile driving." In the U.S. by contrast — including that part of it known as Illinois — transit systems starved for funds, urban areas sprawl, mass transit decays and the auto industry loses markets to technologies perfected abroad. Instead, the General Assembly, like the Congress, is committed to keeping the price of gasoline as low as possible. Suggestions by Gov. Thompson that the motor fuel tax be levied as a percentage of the purchase price — a change which would index motor fuel tax revenues to prices rather than consumption — were dismissed as politically unpalatable. Rather than dampen demand, Illinois (again like Washington) has opted to boost production. Illinois is not likely to ever produce more than a tiny fraction of the oil it needs. Its wells are old, and produce only one-seventh of the oil they produced 40 years ago. But although Illinois may be running out of oil, it is not running out of either coal or corn. There have been predictions that substitutes for liquid petroleum fuels synthesized from coal and/or fuel ethanol distilled from corn and other grains will enable Illinois to become the Saudi Arabia of the next century. James Krohe Jr. is associate editor of the Illinois Times in Springfield; he specializes in planning, land use and energy issues. He is also the author of three other articles in this energy series: "Energy for Illinois: past imperfect, present imperative and future conditional," "Illinois: the Land of Ethanol" and "Energy-efficient buildings: optional or mandatory?" September 1981 | Illinois Issues | 27 |

|

|