|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By CHERYL FRANK Transportation: Move ahead with what? IN THIS DAY of cutbacks, decrementalism, policy blackouts and federal faltering, state transportation officials have the shivers. They think they have good reason. For his part, Gov. James R. Thompson could apparently think of nothing to say about transportation in his budget address that wasn't politically problematic or fiscally ominous. For example, Illinois' federal mass transit aid could reach a "critical mass" point, beginning as early as January, if federal fiscal 1983 cuts come in at the lower range of current projections — an increasingly likely probability, according to Illinois Department of Transportation (DOT) spokesmen. (The upcoming federal fiscal year begins October 1 and ends September 30, 1983, so that federal fiscal '83 money losses would be felt in January.)

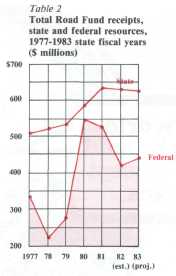

The "variable" federal money for mass transit is not currently in capital expenditure projections, but rather in the ongoing operating expenses for salaries, fuel, repairs, etc. (see table 1). Amazing as it may seem, federal mass transit operating funds generated by the Urban Mass Transit Act are not allocated in any "rational" way to the state transit systems: There is no formula, no apportionment, no set methodology. From state officials' perspective, it is a purely political outcome that leaves them waiting out in the cold. This lack of long-term federal policy and stable funding could well play proverbial havoc, according to mass transit administrators at DOT. The expected capital allocations are on schedule, but the operating expenses could jump the rail. Federal operating funds for the Regional Transit Authority (RTA) may go from $79.9 million (for both fiscal 1981 and 1982) to as low as $49.7 million for state fiscal 1983, a staggering 37.9 percent decrease. Since about 75 percent of RTA funds are allocated to the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA), according to the auditor general's office in Chicago, this could mean a loss of as much as $23 million in federal CTA operating funds. Only 10 percent of federal mass transit assistance is filtered through the state, but the state does have approval power over all dollars, appropriated and non-appropriated, that municipalities and communities receive. On the state politics side, such a reduction, combined with other chronic RTA/CTA problems that may still be around early next year, could set off an RTA "crisis" that would make the one last year look like a picnic. Downstate federal mass transit funds could be cut as much as 50 percent in the upcoming year, from a state fiscal 1982 level of $11.1 million to $5.2 million in fiscal 1983. Rural transit federal funding, now at a state fiscal level of $800,000, could be entirely eliminated if the Reagan administration gets its way. These funding outcomes could, indeed, precipitate statewide "critical mass" for mass transit — for Illinois' governor next year — whether Thompson or his Democratic opponent, Adlai E. Stevenson III. High-powered Gov. Thompson (or his successor) and super-charged Chicago Mayor Jane Byrne — facing the mayoral primary in February 1983 - may once again cross political wires on the transportation platform. The mayor and other RTA political engineers, and there's an ever-growing number of them, will undoubtedly make a run on the state's precarious general funds or some other institutionalized form of state aid. But state sources of transporttation revenue are down or failing to keep pace with inflation. Turning aside from the mass transit picture, Illinois highways may be in for rough going as well. The federal/State "intersection" for highway funding is not yet clearly marked. Last March the Transportation Study Commission criticized DOT for its "ad hoc" method of accounting and complained of the virtual impossibility of tracing federal highway aid and state resources against particular DOT programs or time periods. To be fair, there seem to be good reasons for DOT's patched-over accounting problems: the multiyear nature of capital expenditures; differing federal/state budget cycles; the number of projects involving federal aid; the almost impossible job of accounting for how federal reappropriations «obligated; delays in final federal biding decisions; and the size and complexity of DOT's budget. "Analysis the overall DOT budget is equally challenging as an overall analysis of fcentire state general funds, including It common school fund," according to Barry Wright, former budget bureau malyst for state general funds and currently DOT budget analyst. He thinks It's still learning. 34/May 1982/Illinois Issues By the end of the federal fiscal 1982 jar, federal highway aid is projected lobe down, overall (see tables 2, 3 and I). Federal highway aid is trickling down to Illinois in amounts far below that Thompson had negotiated and planned for, following the 1977 Cross-lown Expressway "demapping" deal in which the feds (with state guidance), issured Chicago and collar counties of H.7453 billion federal dollars, mainly far roads but some for transit improvements. With inflation adjustments, the total owed that area is approaching $2 billion. So far that fat vat of federal funds las been funneled to Illinois at the rate tf only about $100 million a year. As of December 31, the state had spent 180 million for transit and $364.9 million for highways. That leaves at least $1.5 billion unspent out of the inflation-adjusted $2 billion. No one knows for sure if the state will get it all, or when. As the late Illinois Sen. Everett McKinley Dirksen used to say in those famous gravelly tones, "a billion here, a billion there, pretty soon you're talking real money." But that was from his Washington perspective and it was in a more prosperous time. Today's governors, Republican and Democrat, are facing smaller margins for error; they must syphon off every potential saving — a million here, a thousand there. Consider that in state fiscal 1981 alone, Thompson originally proposed a $1,033 billion program — the amount he wanted to put into new road construction to be initiated that year. Compare that figure to his fiscal 1983 $1,102 billion total request for all new DOT appropriations. Then remember that just a couple of years ago he had planned to ask for $800 million for the fiscal 1983 road program. That program has now dwindled to almost 50 percent of DOT's assessed need — down to $440 million. The $440 million still assumes $290 million in federal highway aid, or 66 percent of the total. Several years back, the state had expected the federal share to be at the $600 million level for the upcoming year. Even more sobering to realize is that a large portion of federal aid for the road program is discretionary money, driven by the decisions of the U.S. transportation secretary who is the chauffeur on the Reagan roadmap. There's little room for political error. Undoubtedly, state highway administrators also have reason to fear drastic federal downshifts. Federal Highway Administrator Ray A. Barnhart provided testimony on March 17 before the U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee. He asked for a $7.7 billion obligation level for the entire federal highway program in the upcoming federal fiscal 1983 year (down from the $8 billion in fiscal 1982 and from $8.7 billion in fiscal 1981). He did agree that a minimum of $5 billion more a year (for a total of $12.7 billion) is needed if states are to make any headway in clearing up the backlog of priority projects and in repairing crumbling roads.

May 1982/Illinois Issues/35

On the other hand, the U.S. House has marked its highway budget at the $12.5 billion level. So Barnhart and congressmen agree on the states' estimates, even as Barnhart voices the Reagan administration's official position: The feds can't afford the states' bids. Barnhart also asked for a federal fiscal 1983 total request for all states of only $150 million for Interstate Transfer (IX) funds, which are part of the discretionary money controlled by the U.S. transportation secretary. This year alone, Illinois' IX share was $125 million; should Barnhart's recommendation become reality, this state, and in particular Chicago and northeastern Illinois, would be hit very hard, some might say below the beltline. But it's clear there's a lot of speculation and second-guessing. The question is: Are we experiencing healthy reductions from more lavish times or are we entering a period of real transportation decline? Federal transportation aid is the major variable in the Illinois highway program (see table 2); the state resources appear steady, but not growing. Of course, the feds have their own perspective: They also see alarming evidence of highway deterioration, but not just in Illinois. It is a national phenomenon. Same with bridges. As with the states, there are decreasing federal revenues, with resources shifting to other priorities within the federal budget. They see that Illinois' interstate system is almost complete, and acknowledge that federal resources for major new systems will not be forthcoming. No real surprise there. Jay Miller, Illinois division administrator of the Federal Highway Administration, said, however, "I think we will see a net increase in federal aid over the next few years. For the next decade we will be doing things to hold the system together. We've probably seen the last of any major systems like interstate." Evidently, he sees the declining rate of real growth as at least partially necessary in trimming the fat from federal highway aid to Illinois: "We used to complain about the lack of competition. Now the [highway] industry is hurting. Now instead of an average of 1.2 bids per project, we now have five to eight bids. The shoe is on the other foot."  Stiffer competition for highway construction projects may indeed be forcing greater productivity. One widely accepted measure of productivity is the federal Highway Construction Cost In dex; when the index goes down, productivity is assumed to have gone up. (The index reflects average prices on federal aid contracts greater than $500,000, excluding secondary system contracts, with average 1977 prices 100.) According to the Federal Highway Administration's analysis, the index declined 0.3 percent in the fourti quarter of 1981 from the previous quarter, and this was consistent withal two-year trend of declining bids. though the decline was not steady, the first quarter of 1980 shows an index of 157.9 while the last quarter of 1981 was down to 156.8, reflecting an overall percentage change of -0.7 for that period. The Illinois Construction Price Index, based on state cost measurements, supports the claim that this state's tax-1 payers are, indeed, getting more transportation value for their road budget, even as that budget decreases overall. The state index declined from 151.2 in 1979, to 149.4 in 1980, to 135.5 in 1981, an overall downward change of -10.4 percent. 36/May 1982/Illinois Issues

But these figures alone could be misleading. Administrators could be getting more work out of fewer contractors bidding on more projects, while other contractors have been driven out of the marketplace. Or contractors may be in jeopardy because of long periods of absorbing losses in order to hang onto their businesses. The state could be letting higher productivity out of fewer workers, as some may be laid off, and, a larger perspective, this also hurts the Illinois economy. Some say the state's construction industry hasn't "bottomed out" and if there isn't more work, mainly through the state highway program at more affordable levels of contracting, the state will see inns folding, increased unemployment, and intolerable deterioration of the highway system. Others, less alarmed at these pros-pots, believe that the construction industry will be able to successfully adapt 10 new modes of production. For instance, Miller says: "I don't think it's a risis situation. We have been used to a my fat program here in Illinois. The big shake-up will come in equipment suppliers. The demand for heavy earth-noving equipment is dropping off drastically. A new kind of equipment till be needed — to recycle highway materials on the road right there in place. These machines are called profilers or recyclers." He amplifies: "Heavy grading mar-kets will be less. Now maybe they will diversify, move out of the 'big iron' and get into other areas such as recycling." His big picture does not include supplemental freeways, unless they are "demanded" by the public. Miller thinks the state's completed interstate system, the last leg of which is the East St. Louis bypass (Interstate 255), will be completed by about fiscal 1984, which likely will mean little or no new interstate money after that year.

However, state officials think that if federal interstate aid remains the same in the next few fiscal years, coupled with inflation and anticipated rising bids, the 1-255 project could take much longer. Again, this scaling down of the interstate program represents the changing "demand": from new construction to maintenance, rehabilitation and repair. This latter side of the federal equation, Miller said, will increase to balance off the declining construction dollars. The bulk of new money will come from the federal "4-R" program for reconstructing, rehabilitating, restoring and refurbishing highways. This may present problems to smaller businesses which will need new capital investment to buy the needed machinery for effective competition. The state may be looking at a major transition period in highway business, somewhat analogous to the desired change from heavy industry to high-tech growth, which the governor is now actively encouraging. Miller pointed out that last federal fiscal year, 1981, represented the second highest federal highway aid year for Illinois, but by the end of the current federal year, total highway aid, overall, is projected to be down. Obligation levels, not spending or appropriation levels, are the best indicators of transportation health, state officials say. Obligations indicate the true commitment of federal dollars to state highways, and they are beginning a downward trend (see tables 3 and 4). Annual obligation levels, showing the federal share for major state highway programs (wouldn't you know) do not appear in the governor's budget book. State transportation officials believe they are forward looking. They are ultimately concerned with saving the state highway and mass transit systems from irreversible deterioration. People can't do without transportation — safe roads, bridges and affordable mass transit — any more than they can do without electricity or telephones. □ May 1982/Illinois Issues/37 |