|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

TAKE TIME ... For Electrical Safety!

————————— By John M. Vann —————————

Most Park Superintendents and staff appreciate the importance of regular maintenance and inspection, and the safety benefits that result. Playgrounds, athletic fields, vehicles and pavement are the usual, most recognized maintenance programs. But what about the infrastructure of our parks? Many park personnel fail to conduct maintenance of utilities, such as sewers, HVAC, or electrical systems. Quite often these systems are neglected. The advantages of playground maintenance are well known. Frequent inspections help prevent injury and dangerous conditions from developing. Similarly, what about our electrical systems, particularly high voltage athletic fields? Problems here are rarely obvious to the naked eye, but can severely injure, or even kill a member of staff, the public, or the maintenance man servicing the system. Considering the number of electrical systems in the field, there is tremendous exposure on a daily basis. Regrettably, problems DO occur and, during the past several years, many accidents and tragedies in both Illinois and across the country have prompted us to wonder, "How can we begin to prevent these instances from happening?"

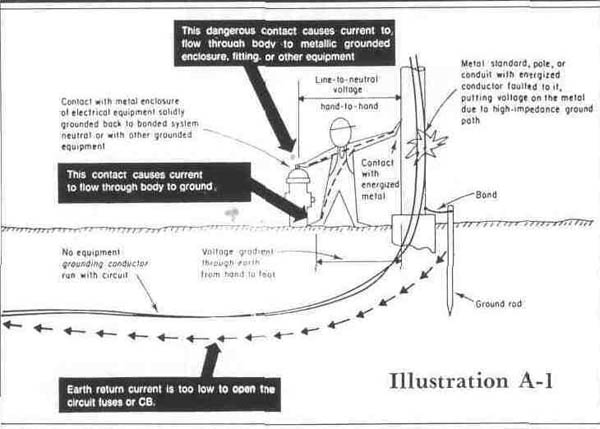

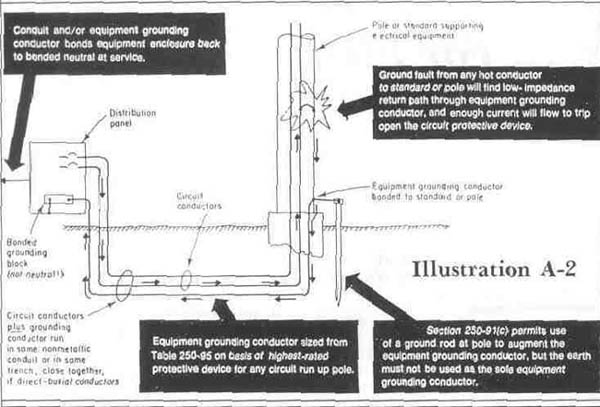

The PNRM Section's An electrical problem comes up. How can we, as responsible managers, take the steps to insure ourselves that our electrical systems are well maintained and up to date? Look no further, because here comes help — the IPRA Park and Natural Resource Management Section's Electrical Safety Manual. The Section has been working for over a year, compiling information and reference material in anticipation of a rough draft release at this year's IPR State Conference. Although frequently delayed due to changes in focus and personnel, the manual has endured. Upon completion, it will no doubt be a valuable tool for the practitioner. "So, what's in it?" you ask. The following, only a sampling of the manual's topics and important points, may be of interest to you or another member of your staff. System Design A major problem in many older, lighted sports facilities is that the installation may not meet present NEC (National Electrical Code) requirements. Quite often fields have been installed as a two wire system, with a single ground rod at each pole providing the sole means for grounding. However, a high voltage electrical system should have at least a three wire system, as required by NEC Section 250-51. The third wire, a low impedance (easy path) conductor returns all the way back to the circuit panel from the pole and connecting fixtures. This wire is either alone, or wired in conjunction with ground wires from all other poles — a method commonly referred to as a counterpoise ground. This third wire allows the circuit breaker to better "see" a problem, thereby shutting it down and preventing damage to the system. It is important to realize that a circuit breaker is not primarily designed to protect human safety, but only the electrical equipment itself. Improper Grounding — A Potential Problem Improper grounding is a common shortcoming that we have found exists in our parks, and, in combination with other factors, is a potentially serious one. This particular problem was a contributing factor in the electrocution of a young boy at the Westmont Park District in 1985. This deficiency has also shown up in reports from other park districts and electrical contractors. The

Electrical Safety (Continued) ——————————————

above grounding rule (see illustrations A-l and A-2) does not apply to just sports lighting. ANY metal pole or conduit that can possibly become "hot", such as pathway lights, parking lots and security lights may need to be grounded in a similar fashion, according to NEC guidelines.

Electrical System Testing Time was that the only way anyone maintained a ballfield light was to wait until it went out, then replace it. This "if it ain't broke, why fix it?" attitude may work for some, but it has no place in today's maintenance mainstream. As systems get older, or become more complex in design, the need for a definitive maintenance program becomes even greater. The resulting benefits are numerous:

Developing a Maintenance Program A maintenance program for electrical systems requires careful planning to determine what needs to be performed, how often and by whom. Much of the work on high voltage systems requires special knowledge or equipment that only an electrical contractor has (or can afford); 480 volt light poles are not the place for force-account, residentially-approved electricians. It is recommended that a certified testing and maintenance contractor be used in most cases. Following are some examples of procedures and tests that may be included in a maintenance program:

Ground-Fault Interrupters A safety device frequently overlooked is the ground-fault interrupter, or GFI. Unlike a circuit breaker, which is designed to protect electrical equipment, the GFI has as its primary function the protection of humans. These GFI's internally self-monitor for amperage loss to outside sources, such as short circuits, bad motors, or frayed cables. GFI's even have built-in test buttons that allow you to check them for proper operation. A GFI safety device may be located at the receptacle controlling only what is plugged into it, or the GFI can be part of the circuit breaker itself. This second method protects any number of services or outlets that are put on that circuit. GFI's have been required by NEC Section 210-8 in potentially hazardous locations for years. GFI's are found near:

A GFI protection device, whether it be at the receptable or the breaker, can have the occasion to "nuisance trip" — turn

off due to a nonhazardous situation such as high humidity — but their value far exceeds some inconvenience. With a little effort, a GFI can be installed that will not create recurring problems. The possible applications are many:

The concerned Superintendent should always explore the use of a GFI system wherever exposure and use of electricity by the public and/or staff may be a possibility. We hope that the information provided in this brief text may be of some assistance to our fellow colleagues in the field and whetted your appetites to check out the Electrical Safety Manual upon its completion. The manual discusses these topics in greater depth, as well as basic electrical terminology (for those of us who don't know the difference between a volt and a bolt), important considerations on new system construction, existing system modifications and updating and maintenance procedures and techniques that may be adapted to your individual needs. In the meantime, think about the systems you now have — are you truly satisfied with what you know about them? Call your electrical contractor. He should be able to help answer any questions you might have.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

|

|

|