|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By BILL KEMP Prison overcrowding: a crisis inviting disaster The Illinois prison system is holding approximately 8,000 inmates beyond its intended capacity of 18,910. There is almost universal agreement among state prison officials, lawmakers and prison experts that the overcrowding problem is reaching a crisis stage. Every month brings a new inmate population record. Today, the Illinois Department of Corrections estimates that it would take 10 900-bed prisons each costing $500 million to build and $100 million to operate just to eliminate the current overcrowding. Overcrowded prisons can lead to an increased number of assaults on staff and disturbances by inmates. They also increase the likelihood of riots. Crowded prisons have few or no services that lead to rehabilitation. The Illinois Department of Corrections, according to some prison reformers, has become the Illinois Department of Prisons. But there's hope. This past legislative session, the General Assembly demonstrated a willingness to address the problem with remedies other than new prison construction. The next several years will be crucial as lawmakers and the next governor tackle this growing problem. The problem, says Rep. Grace Mary Stern (D-58, Highland Park), is so severe that lawmakers are beginning to realize that they have no choice but to act. The reasons for the rapid growth in Illinois' inmate population are simple. First. Gov. James R. Thompson was elected in 1977 on a law-and-order mandate. In defending the current overcrowding crisis, Thompson said in his January State of the State message: '"Get tough on crime,' the people said, and we did. We created Class X sentences mandating prison terms for the most serious criminals. We revamped the criminal sexual assault laws .... We did what we were supposed to do. We listened to the people who entrusted us with public office and took decisive action." Second, the series of so-called "Drug Wars" during the last 10 years have filled state prisons across the nation with drug offenders. According to the Illinois Department of Corrections, in fiscal year 1984, only 7 percent of all inmates were admitted on a drug conviction. By fiscal year 1992, the department estimates that that number will be 33 percent. Not only are there more drug offenders in prison, but they are also staying longer. Between 1986 and 1990, the average time served by drug offenders increased 50 percent. Illinois is not alone. According to a report by the National Council on Crime and Deliquency, the nation's state prison population will increase by 68 percent between 1990 and 1994. The leading cause of the enormous growth can be found in the title of the council report: "Prison Population Forecast: The Impact of the War on Drugs." Dr. James Austin, the council's executive vice president, said earlier this year, "Our nation's prison population will escalate dramatically, and our prison systems will be overwhelmed due to the War on Drugs."

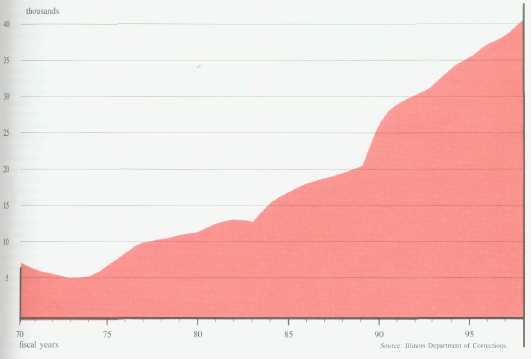

The employee-to-inmate ratio at Illinois prisons has declined since 1985 from 44 employees per 100 inmates to 32 employees per 100, according to Department of Corrections spokesperson Nick Howell. Between fiscal years 1986 and 1989, staff at medium-security prisons increased by 17.6 percent. During the same period, the inmate population in these prisons increased 36.9 percent. That translates into a 20 percent decrease in the staff-to-inmate ratio at these prisons. Calling attention to the severe understaffing problems, more 26/August & September 1990/Illinois Issues than 1,000 American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) walked picket lines at state facilities in April. In response to an alarming Department of Corrections report on prison overcrowding. Corrections Director Kenneth McGinnis said in April, "Something has got to change this scenario of disaster. The lives of Department of Corrections employees are pieces of this puzzle that simply cannot be ignored." Jim Atkins, president of AFSCME Local 1866 at Stateville, is less diplomatic about current conditions. In April Atkins said, "The reality of short-staffing and overcrowding is death. It's as simple as that." A sluggish state economy and stagnant tax revenues, coupled with a no-new-taxes mind-set in the General Assembly after the March primary, meant that the warnings of McGinnis and corrections employees fell on deaf ears in the legislature. Lawmakers slashed $8.5 million from Thompson's proposed $571 million budget for the Department of Corrections. The legislature's cut translated into a loss of 137 corrections employees. Says Howell: "[The] legislature keeps whittling back and whittling back. They took the fat out a long time ago, then took out the marrow a few years ago and are now working on the bone." The employee cut will mean four-to-five fewer employees at Department of Corrections' facilities that include 21 prisons currently operating and two more expected to open in October. The legislature can tackle overcrowding by building prisons or reducing the number of inmates or both. Corrections officials and prison reformers have proposed numerous solutions to ease the prison overcrowding crisis, but they face two potent roadblocks: money and politics. Prison construction is politically popular but extremely expensive. Some lawmakers and reformers have accused the Thompson administration of using prison construction as an economic development tool. Most of the 12 prisons built or currently under construction during Thompson's four terms are located in rural, economically depressed communities that lobbied long and hard for the steady jobs a prison brings. Although Thompson and rural lawmakers would like to build prisons forever, there is not enough money in the state's budget for unabated prison construction and operation. There is agreement among prison officials, reformers and lawmakers that the state cannot "build" its way out of the prison crisis. Between fiscal years 1978 and 1990, the state added more than 11,000 prison beds with the construction of 12 new facilities and the addition of new beds at existing prisons. It Illinois prison adult population, fiscal years 1970-1998  August & September 1990/Illinois Issues/27 costs the state an estimated $70,000 per bed to build a new prison and an additional $16,000 per year to keep a prisoner in that bed. Despite the expansion, Illinois prisons have never been more crowded. In January the state was in the process of adding 2,500 beds to be completed by fiscal year 1991. During this bricks-and-mortar period, the Department of Corrections estimates that the prison population will increase by 4,600 inmates meaning that the Department of Corrections is not even able to get back to square one. In addition, the state simply doesn't have time to build its way out of the crisis. It takes two years to plan and build a prison. The second choice to ease the overcrowding crisis is less expensive but politically unpopular. The inmate population can be reduced by revamping current sentencing laws and/or releasing prisoners early. Corrections officials have joined prison reformers in calling for changes in the sentencing structure. Some reformers like Mike Mahoney, executive director of the Chicago-based John Howard Association, would like the state to evaluate the effectiveness of the 12-year-old Class X sentencing laws that have contributed to the rapid growth of the prison population. Mahoney's group is calling for a moratorium on mandatory sentencing and on the lengthening of prison sentences for crimes, but lawmakers are cold to the idea of even the appearance of being "soft on crime." What's the chance of a moratorium on mandatory sentencing? Slim to none, says state Sen. John Davidson (R-50, Springfield). Mahoney also says overcrowding can be eased by releasing older inmates who are no longer a serious threat to the public. A bolder proposal he says is a viable route to eliminating overcrowding is to set a ceiling on the state's total prison population. Florida has established such a ceiling. The Florida ceiling acts as an emergency measure when the prison population reaches 97.5 percent of lawful capacity. When that level is reached, all inmates earning good-conduct time can receive up to 60 days of early release credits. If the lawful capacity reaches 99 percent, Florida's chief of correction declares a state of emergency, and up to 30 days are deducted from the sentences of eligible inmates. But the idea of releasing hundreds of prisoners over several weeks is not a realistic alternative for many politically astute lawmakers in Illinois.

The crisis shows no signs of disappearing. Long-range inmate population projections by Illinois Department of Corrections officials can be summed up in a phrase: "You ain't seen nothing yet." The next governor and General Assembly will face a problem of enormous proportions. The new governor will have to work with the legislature to make hard political and fiscal decisions. The alternative to do nothing is no longer viable, according to Corrections Director McGinnis. He says that doing nothing is simply inviting disaster. Bill Kemp is a staff writer for Illinois Times in Springfield. 28/August & September 1990/Illinois Issues |

|

|