|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

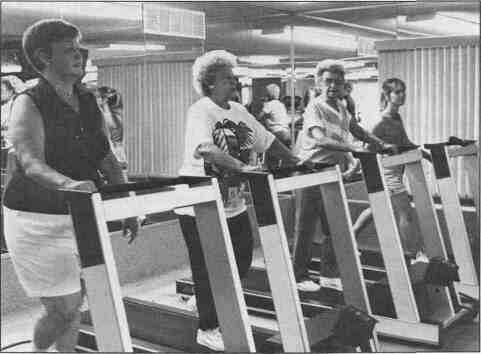

Health and Fitness Programming Tips for the New Senior Population

by Elaine J. Layden

Most program directors are aware of the large number of senior citizens in society today. These over-age-60 seniors who are leisure-time oriented, active adults present a challenge to the leisure programmer. As the baby boomers grow up, retire and become leisure activity enthusiasts, the number is projected to increase. Much attention has been given to this demographic change in our population.

Richard D. MacNeil suggests that this population will soon be making their wishes known directly by "expanding representation of seniors on recreation councils, commissions, advisory boards, and in professional organizations." Until that time, however, the question of what this demographic change means from the program standpoint remains to be reckoned with.

Can this population fit into existing programs? Do they need centers and activities of their own? Do the senior center programs currently offered meet their needs? Are they interested in bingo, craft circles, card games, blood pressure screenings, health fairs, luncheons, organized daytime bus trips, or ballroom dancing? The answers to these questions are both yes and no. What has been offered so far has met the needs of some. Yet, with the demographic increase in numbers, and the decrease in participant age due to an increase in early retirement and improved health care, we find a younger and healthier population for which to program.

Many of these seniors fit into existing generic programs. There are several lifestyle factors distinct to this population that suggest some programming changes are in order.

Foremost among these factors is time. Retired seniors typically have all day to be active and do not need to use evenings and weekends. From a practical standpoint, this is facility down

| Illinois Parks and Recreation | 16 | January/February 1992 |

time, which is more available for programming. Seniors do not need to take programming time away from the working adult. Also associated with this time factor is the providing of more unstructured activities such as open rooms for cards, crafts, etc. Open time for socializing in many cases can lead to the development of very active volunteer and/or action groups, which can unite to provide valuable services to the community.

Another lifestyle factor to be considered in programming is participant absenteeism. Seniors are "on vacation" all of the time. That means there is no "off" time with regard to programming. In fact, depending on the part of the country, programmer's "off" time may be the non-senior population's "on" time. Summers in the Midwest, though often slow in health clubs that cater to the younger population, find that this is when seniors are interested in exercise. It is in the winter months that they escape to warmer climates. Winter makes getting out more difficult. Along with these factors, illness, injury, and/or family crisis may cut into their normally structured day.

Classes need to cope with the comings and goings of these participants. They are not necessarily less committed, but other demands often pull them from their classes. A large class enrollment can help deal with this problem. These classes need to be loosely structured or offered in shorter sessions so that these irregular attendees can participate.

The financial situation of this group needs to be considered when planning programs. Seniors often are living on strict budgets. Many seniors split their year between two locations, either owning or renting a second residence. Their leisure money is spent carefully. Half-year memberships, pay-per-class, selling blocks of classes at a reduced rate, and credit for unused classes, all may be ways of dealing with this dilemma.

An area not yet fully developed is the senior exercise program. "An active exercise program, wisely adapted to the physical changes the human body undergoes after middle age, is an important part of staying healthy into later life," according to Neil Sol, Ph.D. The benefits of exercise to the older adult has had extensive study in recent years.

There is no doubt that major benefits exist, both in slowing the aging process, as well as treating physical problems involved with aging. Though progress may be slower and less dramatic than with the younger population, progress can be documented. Reductions in body fat, weight, resting heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol are all linked to exercise. Increases in strength, flexibility, endurance and aerobic capacity are related to exercise.

Recent articles in The Physician and Sportsmedicine suggest that even unhealthy seniors can benefit from exercise. Conditions such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, osteoporosis, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure should not be deterrents to the senior exerciser.

Seniors who begin to exercise report that they feel better, eat better, sleep better, make new friends, are more relaxed, have fewer aches, have improvements in bodily functions, and have more energy to get through the day. They notice that they can turn their heads to back out of the garage, as opposed to turning their whole bodies. They can reach the top shelf. They can dance until they decide that they don't like the song, and not quit because they are tired. They report that their doctors tell them that they did so well in surgery and recuperation afterwards because they were in good shape.

When planning a senior exercise program, considering the lifestyle issues already discussed is important. This population may need a little extra attention. This group needs an instructor who has been around the block and is experienced in senior programming. They need a person who has some certifications and training to help cope with this special population.

The fourth edition of the American College of Sports Medicine's (ACSM) guidelines for exercise testing and prescription consider the senior population as a special population, but not with the intention of suggesting that they avoid exercise. "Goals for physical activity in this population include maintenance of functional capacity for independent living, reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease, retardation of the progression of chronic diseases, promotion of psychological well-being and provision of opportunities for social interaction," according to the ACSM guidelines.

Guidelines used for assessing risk of exercise and fitness testing no longer use age as a deciding factor, but instead include cardiac risk factors and disease symptomology. This allows exercise instructors more freedom when dealing with this population. Moderate exercise is not recommended for the apparently healthy adult of any age. Since there is a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in the elderly, exercise testing is typically recommended prior to beginning a strenuous exercise program.

| Illinois Parks and Recreation | 17 | January/February 1992 |

Initial screening by qualified staff can simply determine what category participants fall into. ACSM exercise guidelines include cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and muscular strength and endurance as components of fitness in the healthy adult. Programs need to adjust to this holistic picture. Much attention has been devoted to the development of an age appropriate exercise format.

The composition of the senior exercise class should be considered. The needs of this population are as varied and numerous as its participants. It may include people totally new to exercise, long-time fitness fanatics, rehabilitation patients, and individuals who haven't exercised for years and have slightly outdated ideas of what is appropriate. The levels of fitness may be just as varied.

Special classes such as walking, healthy back, relaxation and arthritis exercises are very appropriate. Introductory classes such as strength training for women or aerobics for men may encourage inexperienced participants to try something new. For the more advanced individual, integrating with regular fitness classes is appropriate.

Handicapped access is a must for those who use wheel chairs, walkers or motorized carts. Providing cardiac rehabilitation classes should also be considered. Physician clearances and/or personal waivers may be required.

Instructions need to be given clearly, thoroughly and slowly at first. Repeating and slowing down is essential. Choreographed steps cannot, at first, be too complicated or too quick changing. Seniors' balance, coordination and reflexes are often not as sharp as they once were. Eyesight and hearing are often limited. Attention to visibility and acoustics is important.

Participants should be limited only by their own determination. Goals should be set on a very specific personal basis for each participant. Individual testing is often very effective. The only thing participants can do wrong is to over-do it. Competition, keeping up and comparing should be strongly discouraged. Seniors can be instructed to use established workout rooms if structured classes are not practical.

The importance of the instructor can't be too highly stressed. Trying to capitalize on this new demographic group by using existing instructors can be harmful for everyone. The instructor of these classes needs to be patient and able to help identify progress made at all levels. These are not glamorous classes to teach, nor will the instructor get her own workout in, which often makes finding an instructor difficult. The instructor needs to be able to adapt well to all types of physical problems as well as cope with a generation gap.

Music must be varied from the typical health club, trendy beat. It needs to be slower and identifiable by the group. Much success has been discovered with remakes of the oldies, including anything from the 1920s to the present. Variety is the key to adapting to this wide range of tastes. Hearing problems can be aggravated by poor sound equipment or poor quality recordings. Establishing an appropriate level of volume, making voice commands clear and simple, and helping participants find the best location for them in the room can alleviate some of these problems.

New senior participants, though reluctant at first, if brought into the exercise regimen slowly, carefully and without injury, will become the most committed participants. Their interest in fitness will become vastly expanded as they continue their program. They will want blood pressures tested, cholesterol tested and they will ask questions. They are an extremely rewarding and challenging group with which to work.

When people feel good, they radiate good feelings to those around them. That feeling becomes contagious. Seniors can become a very important part of the recreation and leisure programming field, if program directors take the time to help them.

About the Author

Elaine J. Layden has been a fitness specialist for more than 12 years. She is currently the Fitness Director at Carillon, Plainfield.

| Illinois Parks and Recreation | 18 | January/February 1992 |

|

|