|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By BRETT D. JOHNSON

Down the drain

As river towns tally the cost,

The Regional Economics Applications Lab at the University of Illinois' Chicago campus is studying the economic impact of the flood and hopes to map out effects over a several year period. Ram Mahidhara of the lab said the information will look at how flood damage creates an economic chain reaction affecting companies far from the rivers. "One part of the economy is linked to another; it's not just based on geography," he said. Information was still being collected in August, and Mahidhara said estimates from states in the flood region have to be examined to be sure damage is not exaggerated or, in Illinois, understated. "If there's an impression the state is suffering greatly, its bond rating may suffer," he said. Ellen Feldhausen of the state Bureau of the Budget said the Standard and Poors and Moody rating agencies have asked about flood damage, but she said it was too soon to know whether the disaster will affect the state economy and bond rating. Feldhausen suggested a broad statewide perspective would indicate little effect. "A lot of our tax base is in the Chicago area," she noted. A main impact for the state has been the shutdown of a vital transportation system. With the flood closing all Mississippi River traffic along the state's border to Cairo and the Illinois River from Havana south, barge operators have been forced to lay off workers while businesses seek other transportation. Since opening in 1935, the Illinois waterway has been a major route for the nation's trade, linking Chicago and the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico through a system of locks and dams on the Illinois River and a ship canal from Lake Michigan to the Des Plaines River. Products carried on the waterway includes coal, oil, gasoline, sand, gravel, corn, soybeans, wheat, iron, steel and other heavy freight. Del Wilkins of National Marine Inc., a barge operator in Lemont that moves products from the Chicago area to New Orleans, said 2,200 loaded barges and 900 empty barges have been reported tied up between Illinois and the upper Mississippi. There were 1,075 barges immobilized on the Illinois River alone or in St. Louis waiting to make the trip

22/August & September 1993/Illinois Issues

For oil companies the river closed to traffic has apparently not caused major problems, despite four major companies having refineries along the waterway or on Lake Michigan. Mobil Oil Company, for example, which has a refinery on the Des Plaines River near Joliet, uses pipeline more than barge transport, officials said. Bill Taylor of the American Petroleum Institute said flood concerns are more oriented to oil storage than movement, since most waterway transport occurs with wintertime products such as heating oil. While businesses dealt with the shutdown of transportation on the river, officials and residents also faced the problems of crossing the river. Since the first span was built over the nation's longest river in 1856, from Rock Island to Davenport, Iowa, bridges have become vital to local economies. Nine of the 25 bridges (railroads excluded) from Illinois over the Mississippi were closed during the flooding, and two bridges over the Illinois River were also blocked. Residents of land between the rivers

August & September 1993/Illinois Issues/23 south of US 36 were left on a virtual peninsula with road travel only available to the north. Bridges that were closed included a toll bridge from Niota to Fort Madison, Iowa; both bridges to Missoui from Quincy; river crossings on US Routes 36 in East Hannibal, 54 in Pike, 67 in Alton, the McKinnley Street Bridge in Madison County, and the bridge at Chester. Additionally, two ferry crossings in Calhoun County were shut down, and the Eads Street Bridge in St. Clair County was already closed for repairs. Approaching the bridges and along the rivers, 1,000 miles of roadway in Illinois were closed due to high water, according to the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT). The extent of damage will not be known until the water recedes completely. In the East Hannibal and Quincy areas, where the Sny Levy broke, that could be months. "It's just too early to get an estimate on repairs," said Joe Hill of IDOT's maintenance office. On State Route 3 in southern Illinois sandbags and gravel were used to keep a three-mile stretch of road open by elevating it above the encroaching river. The result was a virtual land bridge over flooded river water, which avoided a detour around the Shawnee National Forest. For railroads, miles of closed track meant rerouting or finding alternate forms of transport. Throughout the Midwest, more than 500 miles of track were underwater at some time and some totally washed away, according to the Association of American Railroads (AAR). Thousands of rail workers were called on to repair flood-affected tracks, removing debris or restabilizing track while traffic was routed on other routes. But AAR President Edwin L. Harper said that although 25 percent of the country's railroad traffic passes through areas that were flooded, consumers won't face higher prices. Cost of rerouting will be absorbed by railroad companies, which are constrained from passing on such costs by tough competition with the trucking industry. "I do not expect to see any increase in the price of a can of tuna, a loaf of bread or a kilowatt of energy as a result of costs incurred by railroads to keep freight operating," he said. Neither is any great food price increase forecast due to flooding of farmland, despite extensive damage. As of the first week in August, 872,000 acres of farmland in Illinois were or had been underwater — 3 percent of the state's agricultural land. Nearly half of the flooded farmland resulted from the Sny Levee break in Pike County, said Mace Thornton of the American Farm Bureau. Another 70,000 acres were flooded due to the intentional levee break near Prairie Du Rocher. Additionally heavy rain this spring in northern Illinois forced corn to be planted later, possibly endangering the crops. "It's going to be pretty touch and go whether that corn yields before we hit frost stage," said Martyn Foreman, who forecasts prices for Agrivisor, a service of the Illinois Farm Bureau. If the crops make it, Illinois farmers may benefit from higher prices caused by shortages in Iowa, Missouri and Wisconsin, Foreman said. Although the price of corn has only slightly increased, and fluctuation is expected anyway. Foreman said soybean prices rose $1 to $1.50 a bushel. "It will certainly be better here [in Illinois]," he said, cautioning that the farming industry will still be hurt overall. "Price never makes up for a bad year." But once the fall harvest comes and farm items are moved to market, Foreman said the price changes will be minimal. "It's not really going to have a big impact on consumers," he said.

The bill for much of the damage, preliminarily estimated by the Illinois Emergency Services and Disaster Agency at $610 million in Illinois, will come from the National Flood Insurance program backed by the U.S. government. Private insurers will only have a portion of the bill. In Illinois, damage covered by private insurers from major storms that led to the flooding will cost about $35 million in claims, said Gary Kerney of Property Claims Services, an organization that surveys insurance companies. With the federal government covering flood damage, Jean Salvatore of the Insurance Information Institute said most of the claims are for loss of business and for damage to homes and other buildings due to storms and not the flood; few claims have been made against comprehensive car insurance for autos lost to rising waters. Regionwide the private insurance claims are estimated to be $655 million, Salva-

24 /August & September 1993/Illinois Issues

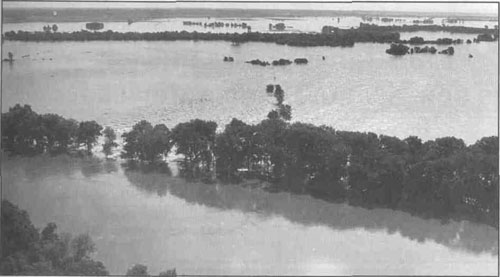

Quincy Herald-Whig photo by Michael Kipley The Sny Levee broke during the flood, allowing the Mississippi River waters to spread out across its floodplain. The view looks east northeast over Illinois. tore said. The cost is a big hit for insurers, but far from the $16 billion bill insurers got for Hurricane Andrew. "It's not, financially, even in the same league as a hurricane," agreed Jerry Parsons of State Farm Insurance. The economic impact for the Bloomington-based company will be reasonably small, despite 19,000 claims, 1,200 of them from Illinois policyholders. State Farm offers insurance covering damage from back-up of sewers and drains, which is why the company expects to pay out $27 million despite the federal government's backing of flood insurance. "The vast number of claims fall under that endorsement," Parsons said. If consumer prices or insurance premiums do not hit the general public, the bill for taxpayers might. Indeed public money being spent on the flood may be the most direct impact for residents outside the flood area. Both the federal and state government worked to provide emergency relief, and road and bridge work will be necessary. Federal funds will cover flood and crop insurance claims throughout the Midwest as well as Army Corps of Engineer work on levees, locks and dams along the rivers. State money has been used for relief efforts, road and bridge work, economic assistance and jobless benefits. Local taxes in towns along the river will be used to rebuild and, in many places, make up for a summer of lost or greatly reduced sales tax revenue. Comptroller Dawn Clark Netsch's office estimated that in the Quincy area alone with bridges and businesses closed, blocking off Missouri consumers, the city may have lost 40 percent of its sales tax base. To help offset some of the loss for local government, Netsch's office expedited payment of $45.6 million in state revenue checks to municipalities along the river. Total impact of lost sales tax revenue for cities along the river and for the state will not be known until possibly October, according to the Illinois Department of Revenue. After the waters recede and people begin to rebuild, a final economic impact is possible, and the attorney general is watching for it. Roland Burris's office, already investigating reports during the flood of potential fraudulent charities, was laying the groundwork to investigate home repair fraud claims, common after a natural disaster. So even after actual economic losses are totalled, criminal economic loss is possible. For the people living along the Mississippi between Dubuque and Cairo, weeks of sandbagging, fighting, fleeing and cleaning have made the flood seem nearly unbearable and, as U.S. Agriculture Secy. Mike Espy said, catastrophic. The disruption to their lives and the economic loss they have suffered have been profound and will be enduring. On a broader scale, the effects of the flood appear less severe and more short-lived. Macroeconomics cannot compensate for the misery suffered by people in the flooded region. But from most appearances, the Great Flood of 1993 won't become the "great economic disaster" for the state of Illinois. Brett D. Johnson is a reporter in DuPage County for two newspaper chains, Press Publications and Reporter/Progress Newspapers.

August & September 1993/Illinois Issues/25 |

|

|