|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By WILFREDO CRUZ

From blue jeans to pinstripes

Daniel Solis sits behind a big, thick oval wooden table, covered with custom-made glass, that serves as his office desk. His dark, pin-striped suit jacket is draped over his chair. Papers are scattered all over the table. The spacious office is flooded with sunlight from the many floor-to-ceiling windows with open mini-blinds. Solis' secretary interrupts on the intercom telephone to say a Chicago alderman is on the line waiting for him. She interrupts again; this time an Illinois state representative is calling. And again: a U.S. congressman wants to talk to Solis. Danny Solis has traded confrontation politics for a seat at the tables of power. He is emerging as a leader as Latino influence grows in Chicago

Times have changed. Some now wonder whether the 43-year-old Solis has mellowed and joined the power establishment he once fought against. Some note that he appears to be a behind-the-scenes political player with some good old-fashioned "clout." He's even part of Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley's kitchen cabinet. Has Solis abandoned his community empowerment ideas? He says not. Solis sees his political insider strategy as a more effective way to empower his community. Solis heads the United Neighborhood Organization (UNO), a community-based group with chapters in three low-income, Mexican-American neighborhoods of Chicago: southeast Chicago, Back of the Yards and Little Village. Solis has worked with UNO since its founding in 1980, first as a community organizer, and since 1986 as its executive director. (In 1989 Solis and UNO's original founders Mary Gonzales and her husband Gregory Galluzzo had a major falling out over control of UNO. Solis says Galluzzo wanted almost total control of UNO. Gonzales and Galluzzo left UNO and convinced the community group, Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, to break away from the UNO network.) Since 1989, Solis has doubled UNO's yearly budget to over a million dollars. He's also doubled its staff to 15, with many more part-timers. During its early years, UNO used protests against city officials to win millions of dollars of neighborhood improvements in education, health and city services. But today, some argue that protests are passe and ineffective. Thus, they see nothing wrong with Solis' increased emphasis on negotiation and collaboration with Chicago's prominent business, corporate and political players. "Danny moved from 20/December 1993/Illinois Issues

Moreover, access to politicians doesn't mean he's abandoned his community empowerment ideas. Just the opposite; it shows "that UNO's obtained its goal of being able to dialogue and influence decisions of policy with either political or corporate players. We're at the negotiating table. We don't have to beat the door down like before," says Solis, in UNO's Chicago offices near downtown. "They've let us in the door, because we represent a constituency that's fairly large." Solis points to a large room filled with telephones. He explains that UNO maintains regular contact with over 10,000 residents from its three chapters. Other Latino leaders agree that alliances with powerful politicians are often necessary. "Remember, Chicago's a very political city," says Migdalia Millie Rivera, executive director of the Latino Institute, a social service group in downtown Chicago. "Some Latino leaders develop relationships with politicians. Others choose not to do that. I think Danny Solis is a highly skilled community leader who's very strategic in his thinking and actions. UNO is very effective at developing grass-roots leadership. The Latino community benefits from having all kinds of leaders." The Latino community has indeed reaped benefits from UNO's involvement in the political process. Perhaps the preeminent example is UNO's pivotal role in helping enact the 1988 Chicago school reform legislation, and its success in working the new system to improve largely Latino public schools. "We worked with UNO and they were very involved in getting the legislation passed," says Don Moore, executive director of Designs For Change, a public education policy group. "They mobilized a lot of people to go to Springfield and lobby. Their work was key." UNO also helps Latinos get elected to the local school councils (LSCs). During the first citywide LSC elections, for example, over 17,256 candidates ran for nearly 5,500 seats. Solis and the UNO staff out-organized everybody. They meticulously trained hundreds of Latino candidates in the art of winning elections: slating candidates, mailing platform flyers, door-to-door campaigning and calling voters on election day. Thus, while inexperienced candidates across the city floundered, most UNO-trained candidates easily won election. UNO actively works with councils in 20 predominantly Latino elementary schools and two high schools in southeast Chicago and Little Village. "UNO helps our LSC a lot. We parents now have a voice in the decisions of our school. We decide the budget and what things to buy. We recently got a lab with computers. LSCs have worked to get parents more involved in the education of their children," says Olivia Parea, former president and now community member of the LSC at Bowen High School in southeast Chicago. Parea says her children, Bowen and she have all improved due to her LSC participation. Three of her children graduated from Bowen and attend college.

December 1993/Illinois Issues/21

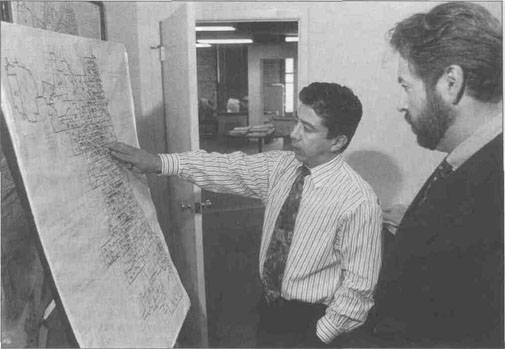

Photo by Richard Foertsch/Photoprose Danny Solis points to a neighborhood map of Chicago where the areas are pinpointed which have concentrated numbers of unregistered Latino voters. He is in the downtown offices of the United Neighborhood Organization, which he heads. With him is Philip J. Mullins, director of staff and policy for the organization. In addition to promoting parental decision-making, LSCs have had a noticeable effect in increasing the number of Latino principals. For years, Latino educators complained of being locked out of principal positions. In 1987, for example, there were 514 principals in the Chicago schools; only 14 were Latino. In 1992, however, 45 of 549 principals were Latino. In 1990, Solis and UNO were the center of controversy when the media reported that two white elementary school principals, fired by their largely Latino LSCs, charged that the dismissals were racially motivated and orchestrated by UNO. However, in a recent separate case, a U.S. Appellate Court panel ruled in favor of four African-American LSC members at Chicago's Morgan Park High School who had been accused of racial discrimination for firing a white principal. The decision is a victory for LSCs and a major setback for some 20 other discrimination suits filed by former white principals against minority LSCs. "LSCs have the power to hire and fire principals, and they have chosen new principals wisely," says Beverly Tunney, acting president of the Chicago Principals and Administrators Association. A July 1993 study on Chicago school reform by a University of Chicago researcher found school reform to be working particularly well in the majority of largely Latino schools. The study concluded that many Latino schools have a "strong democracy," where the principal willingly shares power and promotes positive interaction among students, teachers and parents. Moore of Designs For Change and others credit UNO's assistance to LSCs for the success of Latino schools. Carlos Azcotia, principal of Spry Elementary School, agrees. He says that UNO does a good job of promoting better interaction between parents, children and teachers by encouraging six schools in Little Village to work together as "Schools United For Better Education." While the recent school funding crisis diminished enthusiasm of candidates willing to run for LSCs, Solis isn't discouraged. He believes school reform is working well and represents a good opportunity for empowering Latino parents. Of nearly 5,500 LSC seats, he estimates that over 2,000 are Latino. Says Solis: "LSCs are investing thousands of dollars in areas they feel are important, whether it's computers or bilingual classes, teacher aides or security personnel. Parents have control and power in how their schools are operated to benefit their children. LSCs open the door for parents to become politically sophisticated as to power and the politics of neighborhoods." Besides education, other services have come to Solis' constituents as a result of his political relationships. For example, in 1989 UNO received about $150,000 in Chicago Department of Housing grants for minor repairs of homes owned by senior citizens. Last year, with about $200,000 in Community Development Block Grant monies and low-interest city loans, UNO — in partnership with an African-American owned firm — rehabilitated three buildings containing 31 apartments in the southeast Chicago and Little Village communities. UNO and the firm are co-owners. They rent the units to low- and moderate-income residents. UNO soon hopes to put together a multimillion dollar package of city and federal grants and low interest loans, combined with private dollars, to renovate another 150,000 apartments for low-and moderate-income families in the same two communities within the next few years. In addition, says Solis, "We've gotten Latinos appointed to important boards and commissions and to top and middle-management positions in city government. We're able to recommend people for jobs in the Mayor's Office of Employment

22/December 1993/Illinois Issues and Training. People who are attentive and willing to work with us." Even so, others feel Solis is power-brokering with politicians to push a limited agenda that benefits mostly Mexican Americans and UNO. A common criticism of Alinsky-style groups like UNO concerns their refusal to cooperate with other similar groups while zealously competing for turf, recognition, members and funds. "UNO is out for themselves," says Jose Navarro, community outreach coordinator for Chicago's Lawyer's Committee For Civil Rights. "I see them building their own little empire, instead of building coalitions with other groups like African Americans. Such limited agendas lead to infighting between Latinos and African Americans." Two years ago, Navarro planned to work for UNO as a community organizer. But he changed his mind because he felt its organizing was too parochial. Others question whether Solis is getting too chummy with politicians, therefore losing his — and UNO's — ability to criticize when necessary. Chicago Alderman Ricardo Munoz (22nd Ward), questions why UNO never seems to publicly disagree with Mayor Daley. Munoz explains that during the recent Chicago school crisis the school board proposed using millions of dollars in federal and state Chapter One funds — intended for disadvantaged students — to balance the budget. Some African-American and Latino groups vehemently protested and the board backed off. "They [UNO] were awfully quiet [on that issue]. Why didn't Bertha Magana [Chicago school board member and UNO staff person] speak up?" asks Munoz. Furthermore, Munoz suggests that UNO even tried to place an UNO member who was loyal to the mayor as alderman of the 22nd Ward. About a year ago, Jesus Garcia, the ward's former alderman and Democratic party committeeman and not a strong Daley supporter, became state representative. He recommended that the mayor appoint Munoz as alderman for the remainder of the term. Customarily, the mayor accepts a committeeman's recommendation. But, says Munoz, UNO told the mayor: "We want our own guy in there." Hoping to avoid charges of political interference, the mayor appointed Munoz.

A lifelong Democrat, Solis also maintains friendly relationships with high-ranking persons in Republican Gov. Jim Edgar's administration. And Solis' youngest sister, Patti — whom Solis says he introduced to campaign politics — is director of scheduling for First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. Solis, his parents, four sisters and a brother all attended President Clinton's inauguration. Solis continues to use his political savvy and newfound connections to win important services for his constituents. In 1990, after much negotiation and lobbying from UNO members, the Chicago school board agreed to build five new elementary schools in Little Village. The community is one of the few slated for new school construction. "The board was dragging its feet. For two years we saw no progress," says Juan Rangel, UNO's education coordinator. It appears Solis then used his political influence to speed up the process. Suddenly Daniel Alvarez Jr., an administrative assistant to Daley, began prodding the city bureaucracy. About three months ago, Alvarez became executive assistant at the Public Building Commission of Chicago (PBC), the agency responsible for building the schools. "Nobody wants to see those schools built faster than Mayor Daley. I can assure you of that," says Alvarez. In October, the PBC announced it acquired three of the five construction sites and will begin construction of the first school this month. The school will cost about $6 million, the others a total of about $34 million, says PBC spokesperson Susan Ross. Alvarez is confident all five schools will be constructed "within the next few years." And what will the next few years bring for Danny Solis? He says his immediate passion is his citizen naturalization work. But says Rev. Schoop, "Danny's friends are always teasing him about when he's going to run for political office." Solis says a run for some countywide office, or even for U.S. Congress by the end of 1996, is a possibility, which could make him the ultimate insider. Many people caution, however, that his success on the inside will continue to depend on how well he applies the lessons he learned while fighting on the outside as a blue jean clad activist in the streets of Chicago. * Wilfredo Cruz is a faculty member at Columbia College Chicago. The United Neighborhood Organization (UNO) was the subject of his 1987 Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Chicago. December 1993/Illinois Issues/23 |

|

|