|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO |

Staff |

Links |

Book Reviews

|

Understanding Recovery of primary texts and new insights into history By DAVID ZAREFSKY

|

|

Harold Holzer, ed. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The First Complete, Unex-purgated Text. New York: Harper-Collins, 1993. Pp. 394 with introduction, illustrations, appendix, notes and index. $27.50 (cloth). Gabor S. Boritt, ed. Lincoln the War President: The Gettysburg Lectures. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. Pp. 242 with introduction and notes. $23 (cloth). |

These two books are quite different. One depends on the recovery of primary texts; the other on new insights by historians. Both contribute to our understanding of Lincoln and the Civil War era.

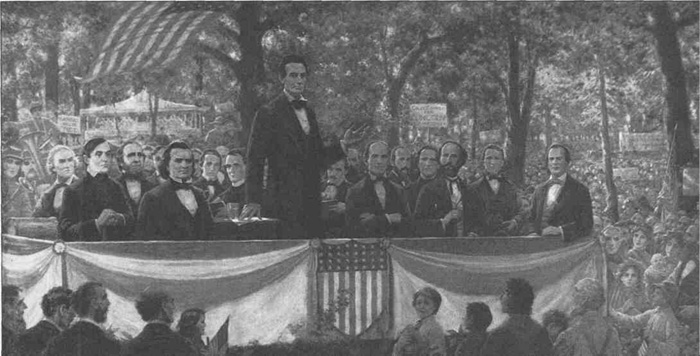

The Lincoln-Douglas debates were stenographically recorded and transmitted by telegraph. But the newspapers of the time were highly partisan, and the reports of the debates differed widely among them. So did the transcripts themselves. Editors would embellish the speeches of their candidate and condense or omit the opponent's statements.

In the fall of 1859 Lincoln decided to seek publication of the debates. To obtain a transcript he combined Douglas's speeches as reported in the Chicago Times with his own as reported in the Chicago Press and Tribune. Lincoln's version of the transcript has been reproduced in most subsequent editions of thdebates. The text compiled by Harold Holzer is different because it follows the opposite procedure: Lincoln's speeches are taken from the Democratic newspapers and Douglas's from the Republican. The resulting text differs in style, though not much in substance, from the "standard" text. Typically, ideas are rendered in rougher form; as Holzer notes, "The level of rhetoric by both of the 1858 candidates was seldom as majestic as folklore suggests."

Readers will find it useful to have this alternate text easily accessible because of the comparison it permits, especially on matters of style. But Holzer goes further, proclaiming in his subtitle that his is "the first complete, unexpurgated text." This is an irresponsible claim not justified by the evidence.

In the introduction, Holzer demonstrates that newspaper editors — the 1850s equivalent of today's "spin doctors" — embellished the texts of those they supported. But they also doctored their opponents' remarks, sometimes by falsely rendering them, sometimes by condensing them and sometimes by omitting them altogether. Holzer implicitly acknowledges this fact, writing that "these newly unearthed rival transcripts may be no more perfectly dependable than the texts produced last century by the candidates' backers ...," but that they may also be no more doctored. Perhaps, but this statement is far different from the assertion that Holzer's is the first "complete, unexpurgated" text. Since Lincoln and Douglas both spoke extemporaneously, and since recording devices did not yet exist, we are destined never to have the "complete, unexpurgated" text. The often

36/February 1994/Illinois Issues

minor differences between Holzer's version and the "standard" text may suggest that the degree of editorial interference was less than we might think.

Incidentally, Holzer's text is not "newly unearthed" either. It has always been in libraries for anyone willing to read the Chicago Times and the Chicago Press and Tribune on microfilm. Holzer has performed a valuable service in making the text readily available, but here, too, the hyperbolic claims overstate that contribution.

The Boritt collection consists of seven lectures, delivered at Gettysburg College, on Lincoln and the war. Interestingly, few of the essays focus on military policy or political strategy per se. One dominant theme is the relationship between emancipation and Lincoln's war aims. James McPherson captures the essence of this link by quoting Lincoln's statement that "we must strike at the heart of the rebellion to inspire the army to strike more vigorous blows," pointing to the important symbolic status of emancipation. David Brion Davis focuses on the moment of emancipation as a kind of rebirth, ensuring "a degree of social continuity and of subservience on the part of the freedmen."

Another theme of the book is the role of the war in inducing the country to define itself as a modern nation. Carl Degler argues that the Civil War was not a struggle "to save a failed Union, but to create a nation that until then had not come into being," suggesting provocatively that America in 1861 was no more united than Germany or Italy, and traces the evolution from "union" to "nation" in the key terms of Lincoln's speeches. Kenneth M. Stampp explains the implications of Lincoln's defining the central issue of the war not as self-determination but as preservation of the territorial integrity of the Union. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. examines how both Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt tested the limits of the Constitution.

Two other essays round out the book. Boritt's concluding essay explores the paradox between Lincoln's decisive war leadership and his earlier abhorrence of violence and war. Perhaps the deepest essay, as well as the richest stylistically, is Robert V. Bruce's "The Shadows of a Coming War," which insightfully traces portents of the Civil War all the way back to the founding period.

These two books are part of a growing new literature reexamining the Civil War. As the central defining experience of the American nation, it cannot be studied enough. Despite Holzer's excessive claims, both these books add something important to the conversation.

David Zarefsky is dean of the School of Speech at Northwestern University, Evanston. He is the author of Lincoln, Douglas, and Slavery: In the Crucible of Public Debate, published by the University of Chicago Press in 1990.

February 1994/Illinois Issues/37

|

|