Silent Sentinels

by Fred Tetreault

A firewatch tower at Big River State

Few images evoke thoughts of forestry, forests and

forest fire fighting more readily than that of a fire lookout tower. At one time, such towers dotted the Illinois

landscape, not just on public lands, but on private forestlands throughout the state as well.

"Dotting the landscape" does not mean there were

a great number of the structures. There probably weren't

more than three dozen statewide. But the nature of their

mission required that they be widely scattered across

the state.

Only four of them still stand.

One is owned by the Vermilion County Conservation District and can be seen in Forest Glen Forest Preserve near Georgetown. It was erected in 1970 and is

73 feet high. The U.S. Forest Service's Trigg Tower,

near Simpson in Pope County, is partially dismantled,

but efforts to rehabilitate it as an interpretive attraction

are being discussed.

The Department of Conservation owns the other two

— one at Trail of Tears State Forest near Jonesboro and

the other at Big River State Forest in Henderson County.

Both are in relatively good condition, and last March

both were added to the National Historic Lookout Register sponsored by the American Resources Group of

Vienna, Virginia.

Firewatch towers were in existence as early as the

1870s, but their purpose was to protect other bumables,

such as a town — Helena, Montana, 1870 — or wooden

railroad equipment sheds — northern California, 1879.

The first firewatch lookout tower built to help protect a

forest was erected on a private woodland in Idaho in

48 • Illinois Parks & Recreation * November/December 1994

1902. In 1915, the U.S. Forest Service constructed its

first lookout in Oregon, a 12-foot by 12-foot log cabin

perched atop Mount Hood at an altitude of more than

11,200 feet.

Fire towers proliferated from that point to the end

of the 1920s, but the message of their value apparently

didn't reach Illinois until the early 1930s.

The reason is easy to understand: The value of forests was not as widely understood or appreciated here

as in some other parts of the country — say, the south

and east, where naval stores and timber for ships had

been driving forces in the settlement of the areas, and in

the northwest, which produced much of the nation's lumber. Fire towers in some of those regions numbered into

the thousands.

A quote from Gifford Pinchot, probably the nation's

first professional forester and former chief (1898-1910)

of what was to become the U.S. Forest Service, sheds

light on the view many Illinoisans and other Americans

still held about forest protection well into the first quarter of the 20th century:

"In the early days of forest fires, they were considered simply and solely as acts of God, against which

any opposition was hopeless and any attempt to control

them not merely hopeless but childish. It was assumed

that they came in the natural order of things, as inevitably as the seasons or the rising and setting of the sun."

Pinchot spent much of his life showing such fires were

entirely within man's control.

By the early 1930s, the federal Civilian Conservation Corps, "Roosevelt's Forest Army," had been established and CCC camps were in operation throughout the

state. It was the CCC which led the way in forest development and protection. The historic army built all 16 of

the U.S. Forest Service's towers in southern Illinois and

at least one — but probably more — of the 11 owned by

the Conservation Department.

From these high vantage points, observers easily

could spot fires anywhere within a 360-degree field of

view that extended six to 12 miles. According to Mary

McCorvey of the Forest Service, the observation stations were placed so their coverage areas intersected.

The system worked well for 50 years.

Illinois forester Dave Gillespie, a section manager

in the Forest Resources Division of the Department of

Conservation, spent the summer of 1961 — literally — in such a tower in Montana's Kootenai National Forest.

He rarely left the 14-foot by 14-foot cupola, perched 40

feet up on wooden legs high on a mountaintop. But he

remembers the experience fondly.

"If you didn't mind being alone, it was great. Along

with beautiful scenery, it offered an opportunity for reading, reflection, meditation, peace and quiet and wildlife

watching," he said. Not everyone could handle the solitude, however. "At least one of the fire tower people in

our area cracked under the strain and had to be relieved

of duty," Gillespie reported.

There also were some hazards to the job and some

negatives. Storms and the potential for running afoul of

bears, cougars or other dangerous critters comprised

most of the former, while living conditions made up the

bulk of the latter.

Since fire towers generally are tall structures — from

40 to 100 feet high — and were erected atop the highest

landsites, such as bluffs and hills, they present a good

target for lightning strikes. The towers were grounded

by thick copper wires, but no one was ever quite sure

what the results of a direct hit might be.

"Generally, we put glass or ceramic powerline insulators on the feet of our chairs to make sure we were

insulated, and we took great pains to avoid getting between two metal objects when there was a thunderstorm

in the vicinity," Gillespie explained. At times he observed "balls of fire" bouncing around the cabin between

metal points, he said. "I don't know if they would cause

injury if they had struck me, but I wasn't eager to find

out."

He had seen bears in the area several times, but on

one occasion a bear got into the woodshed at the base of

his tower. In its zeal to catch the small animals which

often inhabited such sheds, the bear scattered the wood

and severely damaged the structure as Gillespie watched.

It was several hours before the firewatcher climbed down

to repair the damage and re-stack his wood supply.

Another time, a cougar snarled at Gillespie, then

watched and waited behind a nearby tree. After an extended period, the frustrated cat emitted a few ear-splitting screams and ambled off.

"It wasn't likely either of those animals would come

up after me, and even if they did, the cabin was sturdy

and could be entered only through a heavily built trap

door which I could secure with a large bolt," Gillespie

explained. But, he said, the incidents nevertheless were

spooky.

Living conditions included a woodbuming stove to

provide warmth, to heat bath and laundry water and for

cooking; no electricity; once-a-week delivery of food,

water and other supplies; baths in a metal laundry tub

— as often as the firewatcher's water supply held out;

and no refrigeration or ice to keep food edible. "We

could order great big steaks, as many as we wanted, but

they had to be eaten within a couple of days or they'd

Illinois Parks & Recreation * November/December 1994 * 49

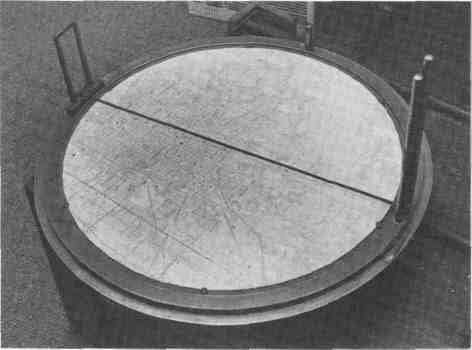

This is perhaps the only surviving

go bad," Gillespie said.

Primarily, the lookout's fare was canned food, perhaps

bacon, canned milk, sausage and potatoes. The Forest Service

provided its station attendants with a "Lookout's Cookbook"

to help them with menu planning. One of Gillespie's favorites was "Lookout's fudge." "I made a lot of that fudge while

I was there."

Another inconvenience was the location of the toilet — an outhouse near the tower's base.

The top half of the roofed cupola was open or could be

enclosed by a continuous window looking out in every direction. A narrow catwalk encircled the outside of the little cabin.

Furnishings included a bed, chair, table, large laundry tub, wood

burning cook stove, a few shelves on the lower half of the

cupola walls, a battery-powered two-way radio, binoculars and

the circular, revolving "firefinder" sight, the instrument used

to pinpoint the location of a fire.

The firefinder, pivoted in the center of the cupola, consisted of a sighting device on a rotary table set above and parallel to a map of the area with the tower as its center. The

device looked somewhat like a sun dial.

A few firewatchers lived in cabins on the ground, but for

most, the tower was their home. Their days were filled by

watching for fires, painting the cabin, sometimes a little reading while also keeping both eyes peeled for smoke on the horizon, cooking and sleeping.

Gillespie came down sometimes at night to walk, if he

was sure there were no unfriendly wildlife to deal with. He

also spent time chopping wood for himself and whoever was

to follow him at the station. And, of course, he had to come

downstairs to use the outhouse.

Once during the summer, he was picked up and taken back

to civilization — the nearest ranger station, which was 25 miles

away — where he could shower, do his laundry properly and

get a haircut. Otherwise, he was on duty from sunup to sundown, seven days per week. His only contact with the outside

world were radio calls to and from the ranger station and the

person who brought food and water once per week.

Fire lookouts were sent to school for two weeks of job

training before being assigned to a tower. Still, finding a fire

and directing firefighters to it were not all that easy, according

to Gillespie. "We watched lightning strikes primarily and made

note of where they occurred. A lightning bolt might start a fire

that would smoulder for as long as 10 days before breaking

out," he said.

Once smoke was sighted, the firefinder was used to pinpoint the direction in relation to the tower. Then the lookout

had to figure out how far away the smoke was from the tower

by comparing its distance with the known distances of certain

other topographical features along the line of sight indicated

by the firefinder.

"Sometimes we'd get lucky and direct the crews to within

sight of the fire. Other times, they'd be relatively close, but

couldn't find it because it was behind a hill or obscured by

surrounding trees. On still other occasions, they'd miss the

fire by a wide margin. Then, we'd have to work together by

radio to work them close enough to find it," Gillespie explained.

"There also were times when the fire was in an almost

50 * Illinois Parks & Recreation * November/December 1994

"All of these problems were eliminated when we began

using aircraft to spot fires and direct crews," Gillespie pointed

out.

Lookouts took great pride in their ability to spot fires and

direct fire fighting crews to them quickly and efficiently. A

great deal of competition existed between lookouts and contests often developed to be the first lookout to spot a fire.

Aerial fire detection began to make fire towers in Illinois

obsolete in the 1960s. Between 1967 and the mid-1970s, the

Forest Service and Conservation Department ceased using the

structures and sold or scrapped all but the few that still exist.

The two agencies shared aerial survey information so that little

duplication of effort resulted.

Twenty-six of the 27 Illinois towers were of steel construction — though two of the Forest Service units had

wooden stairs — and all were between 60 and 100 feet high. All but

one were built between 1934 and 1940.

Only minor differences are seen in their design. At the top

were either open platforms or enclosed cabins. These ranged

from seven feet square to 14 feet square. Some units had stairwells, others utilized ladders.

The lone non-steel tower was at Sand Ridge State Forest

in Mason County. Built of locally cut timbers by state forest

employees in 1940, it stood 100 feet tall. It was destroyed by

lightning in the 1970s.

The state towers stood near Benton, Pinckneyville,

Shawneetown, Lively Grove (Washington County), Royalton

(Franklin County), Aden (Hamilton County), Cypress (Johnson

County), at Pere Marquette State Park and at Trail of Tears,

Sand Ridge and Big River state forests.

Forest Service lookout stations included:

The Big River and Trail of Tears stations were honored

for "meeting those standards of historic and cultural significance as established by the National Historic

Lookout Register." The Trail of Tears structure, documented as having been

erected by the CCC, is 80 feet high and sports a 7-foot by 7-foot enclosed cabin. It was built between 1936 and 1938. The

Big River tower is 60 feet tall and also has a 7-foot by 7-foot

cabin at the top.

Fred Tetreault is a staff writer for the Department of

Conservation's magazine, OutdoorIllinois. This article originally appeared in the October 1994 issue of the publication. *

Illinois Parks & Recreation * November/December 1994 * 51 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |