|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

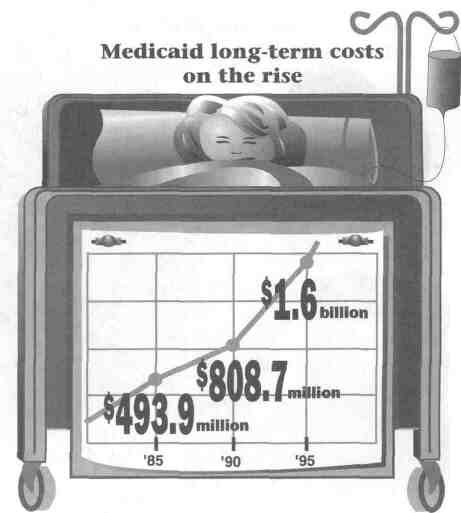

By MICHAEL HAWTHORNE How Illinois got $1.3 billion in the hole The most expensive part of the Medicaid budget is not care for the poor. It's care for the old and disabled. And that's why politicians have failed to tackle a billion-dollar debt When senior citizens check into one of the nursing homes Joe Warner oversees, their middle-class existence often evaporates as quickly as the independence they once enjoyed. Many enter as private-paying patients, but before long they've spent their savings and sold the assets they worked for all their lives. Finally, they're forced to turn to a government program commonly associated with poor people. "I can tell you it could be any of our parents," says Warner, president of Heritage Enterprises, a Bloomington-based company that operates 14 nursing homes across the state. "It could absolutely happen to anyone." As nursing homes can bankrupt the savings accounts of elderly patients, they also threaten to bankrupt the state. And politicians - from Gov. Jim Edgar to U. S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich, from Illinois legislators to members of Congress - are loathe to attack this burgeoning cost because they fear senior citizen lobbies. In fact, after listening to the debate in Washington, D.C., and in Illinois during the past few years, you might get the impression poor people are bankrupting government budgets nationwide through overuse of Medicaid, the health-care program funded jointly by the federal government and the states. Criticizing the program, and its "liberal" creators, currently is in vogue among members of the Republican-controlled Congress and Illinois General Assembly. But while low-income families represented more than 70 percent of all Medicaid recipients in Illinois last year, they accounted for just 30 percent of spending on the program, according to the Illinois Department of Public Aid. The bulk of the cost was incurred by less than a third of the Medicaid

Illustration by Jim Murray

12/April 1995/lllinois Issues population: the elderly and the disabled. Yet when Gov. Jim Edgar and state lawmakers made a stab at reining in Medicaid costs last year, they focused their efforts on enrolling poor people in managed-care programs similar to health maintenance organizations (HMOs). Edgar's Medicaid reform package, which has been stalled by the federal government, failed to address the most expensive and fastest growing part of the Medicaid budget: spending on long-term care. That's a frightening scenario when you consider that Illinois is still saddled with a $1.3 billion backlog of unpaid Medicaid bills. While some of the options for controlling costs in the two most expensive Medicaid populations may be politically unpopular, even some of Edgar's Republican colleagues are dismayed by the lack of action. "Trying things like managed care is important," says Sen. Steven Rauschenberger, an Elgin Republican who chairs the Senate Appropriations Committee. "But care for parent and child already is by far more cost-effective for the state. In my personal view, it's more important to look at saving money on long-term care than saving money on mothers and kids in the welfare system." Lawrence Joseph and Henry Webber, two University of Chicago researchers who recently completed a study of Medicaid spending in Illinois, are more blunt. They say debate about reforming the program is distorted by a "public mythology" that most Medicaid dollars are spent on inner-city poor mothers and children. That simply isn't the case. The U of C study shows welfare families actually represent a declining proportion of people receiving Medicaid benefits — 22 percent in 1994, down from 30 percent in 1983. Meanwhile, the disabled made up 18 percent of the client base but accounted for 47 percent of Medicaid spending in Illinois last year. Looked at another way, Medicaid payments per recipient for the disabled were $9,000 in 1993, nearly seven times more expensive than those for welfare recipients, according to the U of C study. Payments per recipient for the elderly were $7,900, while those for people on welfare were $1,300. "[Suburban Republicans] have made a political decision to hide this reality because these welfare recipients are their constituents," says Sen. John Cullerton, a Chicago Democrat. "It just points out their hypocrisy. If you want to save money on Medicaid, you've got to go to where it's actually being spent." Edgar and other governors had hoped health-care reform at the national level would solve their Medicaid problems. But since a national strategy has floundered, the state's options for controlling costs are limited. Moreover, Joseph and Webber suggest, decision-makers are afraid to reform other areas of the Medicaid program because groups representing the elderly and disabled are potent lobbying forces. One option — forcing senior citizens to contribute to a long-term care program — already has proved to be unpopular. Indeed, seared into the back of every politician's mind is the image of hundreds of senior citizens surrounding the Chicago office of former U.S. Rep. Dan Rostenkowski, demanding Congress repeal a federal program to cover long-term care expenses. (One of the octogenarian protesters jumped on the hood of Rosty's car as the congressman tried to escape.) Health care for the elderly usually is associated with another federal program: Medicare. But Medicare generally doesn't pay for nursing home care for the elderly. In addition, the disabled have to rely on Medicaid while undergoing a two-year waiting period for Medicare benefits. Many of these people were considered middle-class all their lives and never had to rely on welfare before, says Wamer, the nursing home president. But since nursing home care costs

Illustration by Daisy Juarez

April 1995/Illinois Issues/13

thousands of dollars a month, it's easy to see how senior citizens are forced to run through their savings quickly or try to avoid becoming destitute by hiding their assets. Lawyers have created a cottage industry advising the elderly on the latter option, which is frowned upon by state officials. A high-profile example: U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun, an Illinois Democrat, caused a stir when she mishandled a $28,750 windfall payment to her nursing home-bound mother, part of which should have gone to Medicaid. (State officials declined to pursue charges.)

Either way, Medicaid ends up picking up the cost at an estimated $70.07 a day for long-term care. That's a chunk of change that will only grow as the baby boomers age and more people need long-term care. The Department of Public Aid says it is working on strategies to control Medicaid costs for the disabled and elderly. But the department's efforts currently are focused on getting its managed-care plan for welfare recipients approved by the federal government. Department officials also are more aggressively reviewing people who apply for nursing homes to ensure they aren't transferring assets to their spouses, children and grandchildren in order to qualify for Medicaid, says spokesman Dean Schott.

A more productive option would

be to change the way Illinois

cares for elderly people

"We have a real situation where people are siphoning off all their assets, and it just isn't right," says Sen. John Maitland, a Bloomington Republican and former chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee. Powerful senior citizens groups will have a hard time swallowing measures to crack down on asset transfers, he says. A more productive option, says Rauschenberger, would be changing the way Illinois cares for elderly people. "There's an irrational lack of connection in the services the state provides," he says. "The Department on Aging provides home-delivered meals and respite care for people taking care of a family member at home. Then you jump to the case of older Illinoisans whose care needs overwhelm their families and they have to be institutionalized.There's nothing in between those two — no weekend care option, or care available part of the month. We need to build a bridge." Rauschenberger says he's heard estimates that as many as 40 percent of all people in long-term care could be handled at this intermediate level. Adds Maitland: "I've talked with many people who say their mother or father wouldn't have to be in a nursing home if they just got three decent meals a day." State officials also need to improve coordination of care for the disabled, say Joseph and Webber, the U of C professors. They suggest that disabled Medicaid recipients, the most expensive population receiving benefits, should be enrolled in managed-care programs. Costs also could be controlled by assigning physician gate-

Continued on page 16

14/April 1995/Illinois Issues

Gov. Jim Edgar has been criticised by his own party for failing to tackle the Medicaid debt

April 1995/Illinois Issues/15

Continued from page 14 keepers to authorize all Medicaid-financed health services. "A fee-for-service program that provides no coordination of care and rewards providers for delivering more care in all circumstances is not a very promising service model," the U of C study declares. Responsibility for administering Medicaid also should be moved to state agencies that deal with senior citizens and the disabled, say Joseph and Webber. That could help eliminate the perception that Medicaid is just a program for people on welfare. Meanwhile, Medicaid costs continue to go up. In 1985, Illinois gpent $493.9 million Medicaid dollars on long-term care, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health. The bill jumped to $808.7 million in 1990. In 1995, it was up to $1.6 billion — meaning it doubled in just five years. At one of the nursing homes Joe Warner oversees, 12 of the 106 residents were on Medicaid in 1984. That number has jumped to 64 today, he says. The same thing is happening all across Illinois. While Gov. Edgar and lawmakers say they tackled the Medicaid monster last year, their plan for welfare recipients papered over a more serious fiscal dilemma. Edgar says his plan would work if recalcitrant "federal bureaucrats" would sign off, but shifting blame doesn't pay the bills. Until the governor and the General Assembly address reforms in Medicaid for the elderly and disabled, costs will continue to go up, pushing Illinois deeper into debt. * Michael Hawthorne is Statehouse bureau chief for the Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette.

Illustration by Jim Murray

16/April 1995/lllinois Issues |

|

|