|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By DONALD SEVENER

What's a university for?

As a new president takes the helm at the University of Illinois, a view emerges that higher education must rediscover its roots in service to society

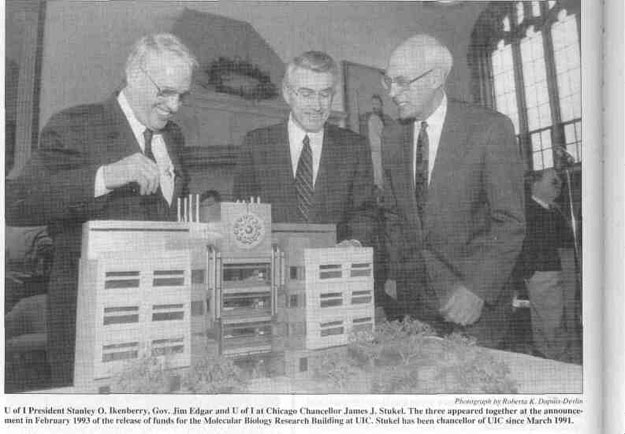

After 16 years as the president of the University of Illinois, the state's most prestigious public university, Stanley Ikenberry has turned the reins over to James Stukel, the chancellor of the U of I at Chicago. Ikenberry's tenure brought impressive growth to the university: the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, the consolidation of the U of I's Chicago campus and medical school, the super computing center at the Urbana campus. Now the university, as well as all of higher education, faces a combination of familiar problems and fresh challenges: adequate funding, demands for greater accountability and, perhaps most significantly, the need to define its role and identity in society in a way that will bring increased public support. Illinois Issues Projects Editor Donald Sevener spent an afternoon interviewing Stanley Ikenberry and a morning interviewing James Stukel to get their reflections on the recent past and foreseeable future of the U of I and higher education in Illinois.

Stanley Ikenberry:

Illinois Issues: Longevity in office seems increasingly rare for presidents of large universities. How have you survived? Ikenberry: Great genes. [Laughter] I think there are a number of factors. In my experience, university presidents are vulnerable in the first two or three years in which they take office. The expectations are high; there are many complexities that take a long while to understand. And, therefore, the opportunity to make a mistake, to in effect ruin one's presidency, to diminish one's effectiveness in the first two or three years is considerable. So, one aspect is simply good luck. I think beyond that, understanding the academic culture, but also being able to relate the university to the outside world and being able to manage and delegate effectively — all of these things are fairly crucial. I think part of it is the general positive predisposition that allows you to get up every morning and shake off whatever frustrations you may have faced the day before. I.I.: How do you view the public perception of universities? Sometimes people see universities as elitist and not relevant to their lives. Ikenberry: There is a certain amount of truth in that. On the other hand, you only need to talk to the parent who has a high-school age youngster getting ready to go on to college to understand that a lot of people in our society think universities are very important. The distance, both socially and economically, between somebody who completes a baccalaureate degree and an individual who does not is growing larger and larger every year. So the importance of a university education to the oncoming generation is probably understood better now than ever before. I think also that our society understands the importance of research now much better, certainly more than we did 25 or 30 years ago, not just as it relates to cancer and heart disease and supercomputing, but in terms of maintaining a competitiveness of both the economy and the society in the United States in a global context. So I think in terms of the demands on the university to address the problems of the cities and the problems of our society in general, the need for universities to be kind of our window on the world with new knowledge and technology and the need for universities to provide the opportunity for young people to grow and develop, the public understands they have a 28/August 1995/Illinois Issues bigger stake in all of this than ever before. Ikenberry traced the emergence of the modern research university, and its challenges for the future, in a lecture at the U of Is Institute of Government and Public Affairs in April. He noted that two forces will influence the shape of higher education in the future: economics and ideology. He said colleges and universities are beyond the days when growth was fueled by significant increases in tax support of higher education, that most projections point to a revenue stream that is "neutral to negative." Also, he said, the nation appears to be going through some ideological upheaval with "shifts in the fundamental values, belief systems and assumptions on which many of our major social institutions are grounded, including not just higher education, hut government, religion, the media, the corporate world and others. It is not surprising that we should sense less consensus on the roles of government and universities." I.I.: What are the implications of this breakdown of consensus for higher education? Ikenberry: In our universities, we expect so much over a broad range of areas and yet those expectations seem to be fragmented among different interest groups within our society. Some view us only as teaching students, others view us as research contractors and still others view us as a kind of service agency. Again, I think part of the responsibility of the university president is to help forge a consensus within the university but particularly on the outside of the university at the highest levels. I.I.: What common view should there be about the purpose of the university? Ikenberry: I think we're in a watershed period where some of the basic assumptions that guided us in the past are now changing. My view is, for example, that undergraduate education is likely to become much more important on most college and university campuses than it has been in the last 10 or 20 years. So I think it's going to be a very good day, a very positive day to be an incoming freshman. I think the cost pressures as well as the quality pressures are going to force our universities to take a fresh look at the application of technology to teaching. We may be on the verge now of a technological revolution in higher education — distance learning, for example, is the frequently used code word, but it really is more than distance learning. Even for residential students now there is a lot of change taking place in the way that teaching and learning take place. They have simultaneous electronic communication 24 hours a day, seven days a week with their professor through the computer. So if you have a difficult math problem at 3 a.m., you can talk to your professor or teaching assistant and get an online answer back without having to wait for four o'clock office hours on Wednesday. I think from the students' standpoint, it's going to be a very positive era. I think it's going to be an economically challenging era where learning to do things differently, more productively, will be just as commonplace in higher education as it is now in every other sector of society. Corporations, for example, have re-engineered, restructured their operations; government is now being forced to look at ways of becoming more efficient, productive. I think universities, if we are going to maintain our quality, will have to do precisely the same thing. I.I.: As you discuss the purpose of the university, I think of a central theme of your speech, that universities should "reaffirm their public character." What does that mean? Ikenberry: Some universities are basically saying the level of state support has diminished or will in the foreseeable future to the point where the university ought to think of itself basically as a private university. That means not just relying less on state funds and more on tuition income and other sources of support that are characteristic of private institutions, but they're shaping the very mission and orientation of the university itself. That's happening now at the University of Michigan; it's happened at the University of Oregon; it's being discussed at the University of California at Berkeley. For some universities, that may be an option. It seems to me it is a terrible loss to the society. And I would prefer to see a radically different solution. It seems to me the alternative solution is for the university to reaffirm its public character and to focus afresh on fundamental ways in which it can meet the needs of the society. Frankly, our society has so many problems and challenges right now that it needs all the help it can get from whatever source it can receive it. The university is the largest, most capable force for helping the society come to grips with its problems that we have available to us as a society. I.I.: Are there forces that impede the ability of an institution like this to reaffirm its public character? Ikenberry: I think the key goes back and will ultimately rest with the willingness of the society to respond to the university's reaffirmation of its public character with a reaffirmation of public financial support. It's that simple. That is, it seems to me, the big strategic bet. If the public ultimately turns its back on the university that's made this commitment, then the conventional wisdom will have proved correct: that it would have been better to privatize at the very beginning and forget about the public interest. I think, to the contrary, a reaffirmation of the university's public character will result in stronger public support. And if indeed that assumption is correct, then that is obviously the way in which the university will also advance its quality. In his lecture, Ikenberry said that preserving academic quality is dependent on increasing efficiency. "We must attack the productivity issue directly," he stated. I.I.: So where do we go from here? Ikenberry: I think that the opportunity for us is reconceptualizing the learning experience for undergraduate students, and making some very tough choices at the graduate level. Very likely we're going to consolidate, eliminate, certainly downsize some of the graduate programs. But at the undergraduate level, I think the real challenge is to rethink, for example, how undergraduate students can most productively and creatively move through the learning process. That may mean doing some of the same things in the future that we've done in the past. But it may also mean equipping students to learn more productively independently, to recognize student achievement that they bring here from high school more readily and effectively than we do, to give students the opportunity to apply technology in the learning process. The answer ultimately will come in a, forgive the term, "re-engineering" of the teaching and learning process.

August 1995/Illinois Issues/29

I.I.: Is the system of incentives skewed toward research accomplishment and publication? Ikenberry: I guess the answer to that question depends upon the kind of university you think you are. For us, of course, we're very heavily a research university. I.I.: Should the reward system be altered? Is there a need to recognize teaching more? Ikenberry: Well, we do recognize teaching. Do we overreward research? Arguably, yes. On the other hand, remember that research monies in the amount of about $250 million a year come to the University of Illinois, and they are not doled out as a matter of right. Our people have to go out and compete for these awards against other faculty members of other universities around the country. They're awarded on the basis of merit. And therefore we should make sure that the incentives of the university recognize the contribution faculty members make in bringing to the University of Illinois that $250 million a year; it would be both counterproductive and outright foolish in a university such as ours not to take that into account in the reward process. I.I.: Anything on your agenda that didn't get done? Ikenberry: Well, nothing so compelling that it would keep me in office for another 16 years. You know, if one could climb one more mountain, solve the state funding problem, if one had been able to transform the internal functions of the university. These are challenges that certainly I didn't get done but I think will be addressed by my successor in the natural flow of time.

James Stukel:

In 1993, Stukel began the Great Cities program, a UIC initiative to link the university's teaching, research and public service efforts to problems in the Chicago metropolitan area. Stukel committed the university to join with other organizations, foundations, businesses and community groups to attack some of the most intractable problems of the inner city. Great Cities is his imprint at UIC and his vision for the University of Illinois. 30/August 1995/Illinois Issues Illinois Issues: Given the demands of faculty, gripes from students, concerns of parents, pressures from the public and legislature and having to do interviews with the press, why do you want this job? Stukel: As I view higher education, it's going to go through some major changes. And I think one of the areas in which all of higher education is going to change is in dealing with societal issues. Because of my experience in Chicago, dealing with the Great Cities program where we were able to focus the institution on dealing with problems of the Chicago metropolitan area, and because we had some success in engaging external people to become involved with us as partners, 1 thought maybe I could be helpful to the University of Illinois in establishing similar linkages between the state university and the people of Illinois. I.I.: You say higher education will have to make a stronger connection to society and its problems. Why? Stukel: Our roots [as a land-grant university] really go back to a time when we were asked by society to deal with these societal issues. As I look at it now, again we're in a situation where locally and nationally there are some serious issues that really begin to threaten the very fabric of our society. Now if that be the case, Jaow can any public university stand on the sidelines and say we don't have to become engaged in dealing with these societal issues? How do you do it, you ask. 1 think it's a question of a pretty strong vision of what you want to do. Why did it work in Chicago? Well, because we could articulate what the vision was, and we talked about it all the time. Every university has lots of individuals who are doing things in the community, but the difference there was the institutional commitment. The chancellor said: "This is going to be our identity." Big difference — an institutional commitment saying: "That's what we're about, that's who we are." We've identified two neighborhoods, in which we made a 10-year commitment — Pilsen, which is a Mexican-American community, and the Near West Side, which is an African-American community. What are we going to do in those neighborhoods? We've initiated many programs, but the general philosophy is that we want to take an integrated approach to dealing with these issues. A house does not make a neighborhood. 1 don't care how much you invest in housing — millions, billions if you wish — if you don't have access to health care, if you don't have a nonviolent environment, if you don't have jobs, then that neighborhood isn't going to work. So, we're sort of a catalytic agent to form partnerships with corporations, community groups, with foundations, with other universities to try to deal with the issues in an integrated way. We realize that parent training is terribly important, leisure time is very important, the health of the child as they come into the room is very important. It's an integrated approach to dealing with these issues. See, these aren't just economic exercises we're talking about; these are real things. We aren't just talking about writing papers here — which we will do, of course, if we find things that work, that's our culture — but actually implementing things, doing things. And if we don't do those things, if somebody doesn't become engaged in these things, our country as we know it and our society as we know it will be vastly different. These problems are not going to go away. So, I think it's good public policy, I think it's good in terms of our self-interest, and I think it's the right thing to do. I.I.: Has this effort changed the public's perception of the university? Stukel: Oh, heavens yes. When I was going through the chancellor's search, it was a very difficult time for us. The Tribune referred to us as University Isolated from Chicago, UIC. If you read the Tribune article when we left, they talked like it was the University Involved in Chicago. I.I.: Is there a perception by the public about higher education much as UIC was perceived five or 10 years ago, as an isolated, insular community? Stukel: I think the people in general hold higher education in high regard. Our problem is with government leaders, foundations, corporate leaders. I.I:Why? Stukel: Well, if you look at national opinion polls, one is that we haven't delivered on our promises of the last decade. Early in the '80s we touted economic development as having a link to higher education; if you invest in higher education, you will see economic development sprouting up all over. Well, I don't know as that has panned out in ways that are demonstrable. Or if it has panned out, we in higher education have not documented it and said, "Look at what your investment has done." Two is access to higher education for underrepresented groups. You look at the change in the demographics of our society and you look at the demographics of higher education, and they don't match up. Many corporate leaders don't feel our young people come out educated. Not from the University of Illinois, but they come from other universities and they can't read, they can't write, they can't talk, so they don't feel we're giving them the type of individual that they need to be competitive in an international market. And fourth, they find that students oftentimes are self-centered; they can't work in groups. So if you look at national surveys and why we have problems, those are four things that come to mind. A recent report in the Chronicle of Higher Education recounting the results of opinion surveys among the general public and corporate and civic leaders confirms Stukel's assessment. But, according to the surveys, another complaint of business executives and local leaders was that higher education had yet to seriously engage in the often painful, but necessary, process of downsizing bloated and inefficient administrative operations and academic enterprises. "The consensus is that higher education has not even begun the restructuring process, and that it has not succeeded in getting costs under control while continuing to provide access to all qualified applicants," according to the Chronicle report. Both the general public and the local leadership, noted the article, "think that higher education could do as much or more than it does now, with less money." As difficult as the push for productivity has been on many campuses, most now agree that the easy part is over. "Most of the low fruit has already been picked," Ikenberry says. Future gains in efficiency and accountability will come in even more difficult and potentially controversial areas that will ask penetrat-

August 1995/Illinois lssues/31

ing questions about the nature and purpose of colleges and universities— the responsibilities of faculty, the quality of undergraduate education, the role of intercollegiate athletics. The Board of Higher Education, for example, has urged colleges and universities to convert the $50 million in state dollars spent on intercollegiate athletics to academic endeavors, a recommendation that many universities have resisted. But perhaps no area touches so close to the heart of the campus than the matter of defining what faculty do. I.I.: Is there a need to look at how the faculty role is defined? Stukel: I think the faculty role has always been pretty well defined. It's a matter of emphasis. They've always been involved in teaching and research and outreach. That is the role of faculty. So I think the definition of the role of the faculty doesn't change; the emphasis and the rewards, what we reward a faculty person to do, will change over time. I think there will be a greater emphasis on rewarding outreach programs. So the reward system will change the role and the way we go about identifying goals and achieving goals will change. I.I. The perception is that the reward system favors research over other endeavors of the faculty, the idea of "publish or perish." Should the reward system change? Stukel: I think we should reward quality where we find it. I.I.: Is it more difficult to identify quality in teaching than in research? Stukel: It's becoming less so. I feel that most know who the good teachers are, who the bad teachers are, who the average teachers are. I don't think that's any mystery. I think students know; if you take their evaluations over a long period of time, they get it right. I don't think it's hard to really evaluate teaching. And I really feel at the University of Illinois that teaching is becoming increasingly more important in the evaluation process. In terms of a tenure position, I will not tenure a person who is a superb researcher but a terrible teacher. Nor will I tenure a superb teacher who's a lousy researcher. In both those instances, I've turned down people for tenure. 32/August 1995/Illinois Issues

No good organization of any type can be one-dimensional. It can't be just research, it can't be just teaching, it can't be just outreach. We have to do all those things. Not everybody has to do all those things, but each unit has to do all those things. And I typically feel that faculty should be doing at least two of those things very, very well. And each unit should do all three things very, very well. I think the University of Illinois does a very good job of undergraduate teaching. Why do I say that, you ask? If you look at the exit surveys, 90 percent of our students are satisfied or very satisfied with their education. How many other businesses have clientele that give a 90 percent approval rating? Our students are happy with their undergraduate experience. I.I.: But you have some lecture courses with a thousand students in them and lots of courses taught by grad assistants. Are people happy with all that? Stukel: Are they happy with every course they take at the University of Illinois? Heavens no. Are you happy with every aspect of your job that you do each day? No. It's the integrated impact that in my view is important. At the end of the day, when they graduate, what are their feelings about their undergraduate education? And it seems to be positive. *

August 1995/Illinois Issues/33

|

|

|