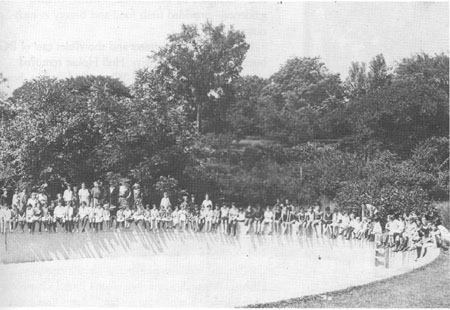

Families at the Joseph Tilton

Bowen Country Club

surround the BCC pool, a gift

of Catherine and Jesse

Colvin, c.1914. (Waukegan

Park District Photograph

Archives)

SPECIAL FOCUS

The Benefits Are Timeless

From Jane Addams' social justice movement to modern-day park district

programming, its clear that recreation benefits all of us

BY SHARON A. LAUGHLIN

| As the century ends. the recreation field is adopting a "new" philosophy called outcomes- or benefits-based recreation. This philosophy identifies community needs and responds with recreational programs that meet those needs. At the Joseph Tilton Bowen Country Club in Waukegan, ILL., benefits-based recreation is a timeworn philosophy put into action. It started with 19th century reformer Jane Addams and continues today with the professionals and elected officials of the Waukegan Park District. |

Families at the Joseph Tilton

Bowen Country Club

surround the BCC pool, a gift

of Catherine and Jesse

Colvin, c.1914. (Waukegan

Park District Photograph

Archives)

|

Advocacy for the disadvantaged took root in Chicago in 1889 at Hull House. Championed by settlement house leader, Jane Addams, reformers organized on behalf of immigrants' rights, juvenile justice, political reform and social welfare legislation. At Hull House they headquartered to battle the prevailing social theory that some were meant to have and some were not. As Hull House raised social consciousness on the national level, benefits programs were provided locally to Hull House neighbors in the crowded alley and apartment housing around Taylor and Halsted streets.

Benefits-based recreation flowered at Hull House, where a mix of social and recreational programs fulfilled familiar community needs: child and health care, social interaction, and recreational opportunities. Always intensely interested in children, Addams yearned to establish a refuge beyond Hull House and in the country, where the youngest could experience its "understanding atmosphere." In 1912, Hull House treasurer Louise deKoven Bowen donated 72 magnificent acres in Waukegan to Addams—the future site of the Joseph Tilton Bowen Country Club. At Bowen Country Club, Addams would perfect benefits based recreation.

In our constantly changing urban settings, there are magical places that retain their unique sense of time, and the of their history earns

September / October 1997/ 15

SPECIAL FOCUS

Left: Activist Jane Addams and first BCC director Thora

Lund at the Waukegan club.

(Waukegan Park District

Photograph Archives)

|

Right: Excited campers and counselors depart Waukegan

station en route to Bowen

Country Club. (Waukegan

Park District Photograph

Archives)

|

them listings to the National Register of Historic

Places. Waukegans Bowen Park is one of these places.

Bowen history begins with its first famous resident,

former mayor of Chicago John C. Haines, who retired

to his Waukegan farm in the 1870s. Haines remodeled

the small Greek Revival farmhouse with grand room

additions and a new Italianate architectural interpretation. After his death, the farm—situated on splendid

rolling acreage with transverse ravines and old-growth

forest on a bluff overlooking Lake Michigan—was

placed on the market. Waukegan mayor Fred Buck

targeted the site as a potential city park. Despite fund raising efforts, funds to purchase it never materialized.

The "Haines Park" location, two miles from the urban

hub of Waukegan, proved its undoing. That same

feature secured its sale to Mrs. Bowen, and in the

summer of 1912, Bowen Country Club (BCC)

opened to mothers and children

from the Hull House neighborhood.

They came by train from Chicago and walked north along Sheridan Road from the Waukegan station to the gates of Bowen Country Club. Most locals knew them only in passing, because their club was private. Like all private clubs, BCC charged a membership fee according to the age of each participant, ranging from $ 1 per week per child to $1 per day for adults. Inability to pay never kept a child from attending BCC. The fee gave members a sense of ownership as it removed the stigma of a charitable camp.

They were a culturally diverse lot—Italian, German, Russian, Irish, Greek, African American, Mexican— representative of Chicago's exploding immigrant population. The grounds were available first to these Hull House families, but eventually others came to the camp during the two-week sessions conducted continuously throughout the summer. Fragile Chicago Heart Association patients and other convalescents became welcomed visitors.

Soon cottages named for philanthropic donors and Hull House associates were constructed throughout the grounds. Rosenwald Cottage housed mothers and babies, young girls and boys occupied Smith and Hutchinson cottages, and the ravines separated the teen boys in French Cottage from the teen girls in Lansingh.

Each cottage group was under the care of young volunteer counselors on break from college, who received training with the Chicago Camping Association. Counselors conducted their groups on camp rounds that included visits to the swimming pool, tennis courts, baseball diamond and evening campfire for stories and songs.

The old Haines house became the residence of a succession of three BCC directors and their families; Thora Lund (1912-1938), Ada and Bob Hicks (1938- 1958), and Robert "Dib" Mulligan (1958-1963). In 1929 Mrs. Bowen built Lilac Cottage so that she and Janes Addams could visit the camp without inconveniencing the other guests. The camp guaranteed three meals a day and bedtime cookies prepared by chef Oscar Robinson and served on blue willow china in the Commons dining room. A vegetable garden, lovingly tended by mothers, and formal floral garden—designed by Bowen's Bar Harbor, Maine, gardener—provided fresh food and beauty at each camp table.

By the 1960s, the streets and shorelines east of BCC bustled with urban activity. Hull House removed camp activities to a remote Wisconsin location, but the heart of BCC remained in Waukegan. Waukegan park commissioners bought the site in 1965. Not all the original buildings survived 50 years of heavy use, but enough of the Bowen Country Club remained to secure listing to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Today Bowen Park retains its magic and extends its legacy. In the southwest corner of the park, in the Bowen Heritage Circle, the farmhouse (undergoing extensive restoration) has become the Haines Museum and the home of the Waukegan Historical Society. Lovely Lilac Cottage houses the J.L. Raymond Historic Research Library, Cultural Arts Department staff, and is the center for traditional arts and crafts

16 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

THE BENEFITS ARE TIMELESS

classes as well as mini-lecture experiences.

Goodfellow Hall, where dances, songs, and plays were shared by BCC families, has been incorporated in both structure and spirit into a larger multi-arts complex known as the Jack Benny Center for the Arts. The Waukegan Community Players theater company occupies Rosenwald Cottage, and the Lilac Formal Gardens have been reestablished—their graceful pathways and a new gazebo are peaceful destinations for locals and a colorful backdrop for summer weddings.

At Bowen Country Club, benefits-based experiences were recreation and social. Tennis, swimming, hiking and the arts wove a tapestry of experiences that provided escape and enjoyment to the neediest. In the process, BCC lifted participants to new levels of social sophistication.

The Waukegan Park District, in the pattern set by BCC, has expanded its program base to offer those with limited life experiences opportunities for growth, social interaction, and beauty. Promising recreational programs such as Youth for Tomorrow and the Genesee Street Recreation Club serve children at outreach sites through recreational activities, homework assistance and mentoring. The Jack Benny Center in Bowen Park provides scholarships to students otherwise unable to afford arts training. At the Haines Museum, student volunteers conduct tours and manage museum projects. This is benefits- based recreation, Bowen Country Club style.

Something old is new again at the Waukegan Park

District.

SHARON A. LAUGHLIN

is the cultural heritage specialist for the Bowen Heritage Circle, Waukegan Park

District.

|

When I first came to Waukegan

in the summer of 1948 to work

as a counselor at the Hull

House summer camp, I had no

idea that I was beginning what

would become the most significant experience-of my life.

Growing up in a small town

setting in Missouri, I had

encountered big cities, tenements, Italians, blacks, Catholics, pizza, and other such "exotic" things only in an

imagination stimulated by years of reading. But I had

also read of Jane Addams and her Hull House and had

chosen to attend Christian college, a small private

girls' school, because I knew it offered students the

chance to apply to work at the Hull House summer camp.

What I found at BCC, what brought me back every summer through 1953, is hard to explain to anyone who had not been a part of it. In a setting of great beauty, with its forests, ravines, flower gardens and yellow-painted cottages, overlooked from the top of the hill by the Farmhouse and Mrs. Bowen's Lilac Cottage, people of many ages, races, religions and ethnic backgrounds lived, worked, played, ate, sang and danced together in an atmosphere of joy and harmony. There was a feeling of family, based on the acceptance of each person as an individual. Among the staff was a feeling of being part of a continuing tradition and commitment to values and attitudes which could change lives for the better—and which would stay with us, shaping our lives long after we left BCC.... |

|

—excerpted from a letter written by former camp counselor Margaret Carlton "Mac" Misiak, for the 1995 history publication about the Bowen Country Club. Photo above: Margaret Carlton Misiak. Photo below: Aerial view of Bowen Park, c. 1965. (Waukegan Park District Photograph Archives)

|

"In this place nature seemed to have combined all desirable things."

—-Jane Addams, from her presentation at the |

|

September / October 1997 /17