|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

THE

FINAL

AN ORPHANAGE IN HARVEY, ILLINOIS • 1895-1918 BY DAVID C. BARTLETT AND LARRY A. McCLELLAN

A REMARKABLE LIFE

At the end of the nineteenth century, a remarkable and world renowned African American woman came to live in the suburbs south of Chicago and established the first orphanage in Illinois for African American children. At the time of her death in 1915, the Chicago Defender called Amanda Berry Smith, "the greatest woman that this race has ever given to the world." For fifty years following the Civil War, she followed paths which led her to prominence as a black woman in a society dominated by white males. She was one of the few African American women to gain visibility in the Women's Christian Temperance Union and was closely connected to the work of the Colored Women's Clubs. These clubs were a major element in the African American expression of the Progressive Movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

20 I L L I N O I S H E R I T A G E Amanda Smith was born in slavery in 1837, the oldest of thirteen children. Her parents were slaves on adjoining farms in Maryland. Through great effort, her father was able to buy his own freedom and eventually paid for the freedom of his wife and children. The family then settled in Pennsylvania. She married twice, but both husbands died—the first during military service with an African American unit during the Civil War. From these two marriages she had five children, four of whom preceded her in death. Only her daughter, Mazie, survived into adulthood. In addition, she adopted two young African children during her travels and ministries in Africa. By 1869 she was without husband and becoming deeply involved with church-related activities. Although she had only a few months of formal education, she was a compelling speaker and singer, and wherever she traveled, people responded to her engaging personality and spiritual power. For the next nine years, she preached in African Methodist Episcopal churches, to gatherings of Methodists, and at "holiness" meetings throughout the eastern and midwestern parts of the United States. One commentator wrote that her "... simple, Quaker-like dress and scoop bonnet, together with a rich contralto voice with which she would break into song when inspired, made her a person not easily forgotten." In 1878, friends suggested that she consider working with churches in England. She responded to this offer, and after a year in England, spent two years working with churches in India. Years later, a Methodist bishop who had served in India wrote that "During the seventeen years that I have lived in Calcutta, I have . . . never known anyone who could draw and hold so large an audience as Mrs. Smith. . . I had learned more that had been of actual value to me as a preacher of Christian truth from Amanda Smith than from any other person I had ever met." After returning to England in 1881, she traveled to Liberia and spent almost eight years in ministry in West Africa. There she worked with churches and helped to establish temperance societies. In 1890, she returned to the United States, and after two years of preaching and related work in the East, she came to settle in the Chicago area. During this period, she was a national representative for the Women's Christian Temperance Union and a friend of Frances Willard.

While living on the East Coast, she was urged to write her autobiography. Written at the home of friends in Newark, New Jersey, it was published in Chicago. Originally published in 1893, it has been reprinted in at least six editions during the past one hundred years. An Autobiography, The Story of the Lord's Dealing with Mrs. Amanda Smith, the Colored Evangelist has become one of the better-known works by nineteenth century African American women writers. From her Autobiography and subsequent biographical research, a fairly clear outline of most of her life and work is available. However, information has been scattered concerning the final phase of her life in Harvey, Illinois, and the opening of the orphanage.

SETTLING IN HARVEY, ILLINOIS

In 1893, Chicago hosted the Columbian Exposition, which was probably the greatest of all the world's fairs. Some estimates suggest that ten percent of the population of the United States came to the Exposition, and much has been written about the impact of this fair on both Chicago and the entire country. The allure of the Exposition spurred a remarkable amount of economic development activity both in Chicago and in nearby suburban areas. Part of this was reflected in the development and advertising of Harvey, Illinois, as a planned temperance community twenty miles south of Chicago. The location was on the Illinois Central Railroad main line, and special trains could easily run from the Exposition down the line to Harvey so visitors could look at this special city in the making. Founded in 1890, the Harvey Land Association began significant development in 1891 and by 1893 was ready to take advantage of the attraction presented by the Exposition. In addition to the potentials for land sales and residential and industrial settlement, several hotels were built in Harvey to accommodate visitors to the region during the Exposition. Turlington W. Harvey and other

I L L I N O I S H E R I T A G E 21

investors who sought to develop Harvey were deeply tied to the work of Dwight D. Moody, the most famous evangelist of the day. Moody and his organization used the attraction of the Columbian Exposition as an opportunity both to reach far greater audiences with their evangelical message and to promote Harvey as an ideal alternative to the discomfort and seductions of the big city. This process and the interaction of economic development and social experimentation is well reflected in James Gilbert's Perfect Cities: Chicago's Utopias of 1893. In this context, Gilbert points out that Harvey was unique in advertising its moral, religious and temperance character, an approach not used by other real estate developments. This was seen in the first few years with the creation of organizations including the Equal Suffrage Association, the Prohibition Club, the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and the Royal Templars of Temperance. The emergence of this unique community, with its deep connections in evangelical and temperance circles, made Harvey a logical location for an orphanage. Amanda Smith had moved to Chicago in 1892 and by 1895 was actively involved in her plans for an orphanage for black children. Harvey could be an ideal environment for orphans—a community of faith opposed to the scandal of drink. A biography of Smith published in England shortly after her death, summarized her struggle to create the orphanage: "When her book was finished and strength and energy began to return, her active mind developed a new form of labour. Her plan to erect an orphanage, where destitute coloured children could be cared for and helped. With infinite labour she collected sufficient money to buy land and build a house. She met with many discouragements, but pressed on, traveling from Camp Meeting to Health Resort, losing no opportunity to publish her scheme; but those willing to assist a coloured woman were poor themselves, and the money came in very slowly." In reinforcing these connections, Amanda Smith had been involved with the WCTU from 1875 and the beginnings of her evangelistic work. When she returned to the United States in 1890, she continued to be active in the work of the WCTU and in 1893 was made a National Evangelist of the organization. The Union Signal, the national magazine of the WCTU, had regular comments on her work through the 1890s and noted her activity with the planning and building of the orphanage. In its report on the 1891 World Convention of the WCTU in Boston, The Union Signal reported that "Mrs. Amanda Smith, 'God's image carved in ebony' being noticed in the room, was called to the platform, introduced and requested to sing." She began the necessary work of raising funds for the orphanage in 1895, and it opened in 1899. As suggested in the quotation above, the funding came from a variety of sources. These also included the receipts from the sales of her Autobiography, lecture and preaching fees, and private donations, including some significant support from temperance groups in Great Britain and African American Women's Clubs in Chicago. She also received important contributions from Julius Rosenwald, philanthropist and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. In 1905, Smith published an appeal in Chicago's Broad Axe for aid from the African American community. She asked for help in raising $1,000 for "bills now due." In Harvey, she published a small and occasional newspaper titled Helper to publicize and support her orphanage. An advertisement for the Amanda Smith Industrial Home in Helper proclaimed that the Home was "Incorporated in 1906 for the Care, Education and Industrial Training of Orphan, Destitute, Needy Children, and especially those of colored parentage." This ad also stated that the institution was "Supported Entirely by Voluntary Contributions." The home, of course, had been in operation for several years prior to the formal incorporation.

While still living on the South Side of Chicago at 2940 South Park Avenue, Amanda Smith had purchased her first property in Harvey in 1895. The cost was $6,000, and she evidently sought to have the building paid for before opening. As reported in a local paper, on June 28, 1899, "In a wild storm of wind and rain, a large company was gathered at North Harvey, Illinois, for the opening of the Orphanage." The effort began debt free, with the one building, an endowment of $288.00 and five orphans. When Amanda Smith decided to establish the orphanage after finishing her book, it is obvious that she had seen and known the effects of discrimination and was willing to discuss and deal with issues of what we would now call racist practices. Because of her multiple involvements in church and temperance organizations, she was no doubt well aware of both the growing discrimination and segregation in urban areas and also the needs of black children. She may have been urged to settle in Chicago by Frances Willard or others in the WCTU, and upon her arrival may have known instances of

22 I L L I N O I S H E R I T A G E direct discrimination against black orphans. For the most part, social needs were handled by private charities, and although the black population of the Chicago area was relatively small in the late 1890s, segregation by race in institutions was already underway. Whatever the direct or indirect causes, Amanda Smith's response was consistent with other reactions within African American communities. In the context of the "progressive" movements of the time, particularly in the cities, by 1910, W. E. B. DuBois had identified the existence of hundreds of black charities nationwide. It seemed clear in the face of continuing and growing discrimination that, not only in the South, but throughout the country, the mutual aid tradition within African American communities was necessary in caring for the elderly, the disabled and others in need, including orphans. This tradition of mutual aid is reflected in Allen Spear's Black Chicago in the creation and growth of institutions by and for African Americans in the "Black Belt" on Chicago's South Side. One element in this was the emergence of the Colored Women's Club movement in the 1890s. These clubs became particularly important in supporting various social welfare activities including the opening of kindergartens, residences for young women and for the elderly, and various kinds of community education programs. African American women involved in these clubs knew the work of Amanda Smith, and from 1900 through 1918, many were directly involved with the orphanage. In a 1915 issue of Crisis, the national magazine of the NAACP, an article, "Some Chicagoans of Note," ended by mentioning five women, with a detailed paragraph on only two: Amanda Smith and Ida B. Wells (Barnett). Along with others who gave leadership to the clubs, Ida B. Wells had served on the Board of Directors of the orphanage in Harvey. The clubs also were a source of funds for supporting the operations of the orphanage. This was especially helpful since the Amanda Smith Home was the first, and for some time the only, orphanage for black children in Illinois. Over time, the Home grew both in the number of children served and in the size of its facilities. During the ten years between the United States Census in 1900 and the enumeration in 1910, the institution grew from twelve to thirty-three children. In 1903, a State of Illinois inspector visited the Smith Home and reported that it consisted of one brick and two frame structures, with an estimated value of $11,000. There were thirty children (ten males and twenty females) in residence, supervised by three salaried attendants. The children appeared to be well treated, "the food furnished is of good quality," with meat twice a week, and they "are required to bathe weekly." It was noted that children were sent by the Cook County Juvenile Court, "but so far the county has paid nothing for their support." The Home was "supported by donation and from the sale of newspapers published by Mrs. Smith." The inspector declared that he was "satis-

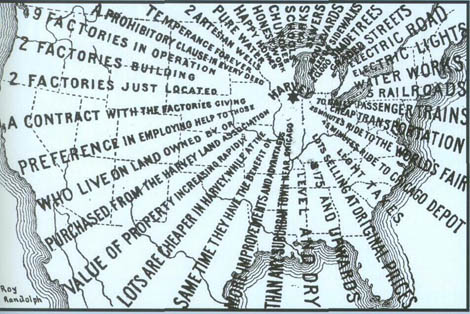

An illustration from promotional literature designed to attract residents and businesses to Harvey, Illinois. Courtesy of the Illinois State Historical Library.

I L L I N O I S H E R I T A G E 25

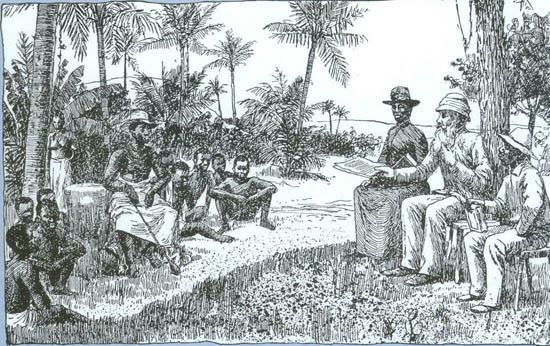

Amanda Berry Smith and Methodist Episcopal Bishop William Taylor working as missionaries in Liberia.

fied that this institution is worthy of support" and that it be certified that "the institution is competent to receive children committed to its care." This positive report was contrary to later State evaluations. In October 1905, Charles Virden became the State's inspector. On his first visit he found "Amanda Smith, an elderly colored woman ... in charge and she furnished funds by solicitation among friends and interested parties, gathering a large portion of same from a number of eastern states as she was widely known as a colored evangelist." He noted that despite Smith's valiant efforts, the Home faced a major problem with its debt. On subsequent visits he observed a "lack of proper supervision," which he attributed to the fact that "Miss Smith was absent gathering funds a great deal of the time and because of her advanced age she was confined to her room much of the time that she was at the institution." Virden states that although the Smith Home did not meet minimum requirements for State certification, its certificate was renewed, "because this was the only institution of importance in the state for the care of colored children." Thus, the Home had its certification renewed every year until it was destroyed by fire in 1918. It never reopened. Amanda Smith provided direction and care for the Home until illness forced her to retire in the autumn of 1912. George Sebring, a wealthy supporter and real estate developer, offered her a cottage for her retirement in Sebring, Florida. Several months after moving, she wrote to the editor of a journal at the Tuskegee Institute and included these observations: "Through failing health I was

24 I L L I N O I S H E R I T A G E obliged to give up the work of the Amanda Smith Home in Harvey, Ill., and I told the Board that they must get someone to take charge of the work. I was not able to carry it any longer and they succeeded in getting a man and his wife and the work has been turned over to them. They are young and am so glad to be relieved of the care and the burden which became too much for me at my time of life I am already past my 76th birthday, Jan. 23rd. Some kind white friends have given me a home here during my life time, will look after my other needs so that I am relieved of the care and anxiety. The mild climate suits my condition of health and I am better since I came here." Amanda Smith died on February 24, 1915, and George Sebring arranged for her body to be returned to Chicago and buried near Harvey. A group of white clergymen accompanied her casket to the train in Sebring, Florida. On March 1, 1915, one of the largest funerals in the history of the African American community in Chicago honored her memory. After her death, the orphanage continued to decline until the State was at the point of revoking its certification. The threat of this action led to an overhaul of the Home's Board of Directors. Some members of the Board were forced to resign. A former Board member, Edward C. Wentworth, was retained and made president of the new Board—joining Ida B. Wells (Barnett) and three remaining black members of the Board. The involvement of these women on the Board reflects the activity of women leaders in both the white and black progressive political and social movements in Chicago. In spite of the intervention and support of such leaders, for a variety of reasons the orphanage continued to struggle with serious maintenance, staffing and financial problems. The absence of Amanda Smith added to the dilemma. When the orphanage burned in 1918, efforts by Board members and others, and also by leaders in the City of Harvey, were made to restore it, but the resources were insufficient. Thus, the focus of Amanda Smith's final ministry came to a close.

Editor's Note: In 1991, a special marker was placed on Amanda Smith's grave in Washington Memory Gardens in Homewood, a few miles south of the location of the Home. On April 23, 1991, the House of Representatives of the State of Illinois passed a special resolution to honor the memory and rare accomplishments of Amanda Berry Smith.

I L L I N O I S H E R I T A G E 25

|

|

|