FEATURE ARTICLE

BY DR. KEVIN MARKS

| The truth is that there is no guaranteed safe ice thickness. |

Have you ever received a phone call from a member of the public or a commissioner with the following comments: "Why haven't you cleared off the pond for skating? There's been ice out there for two days!"

Some park and recreation agencies struggle with the decision of when to open up areas like ponds and lagoons for ice skating. This difficulty and indecision can be intensified as the news media annually headlines an incident in which a child has fallen through the ice in a nearby community. Or maybe, in die past, one of their own vehicles has fallen through the ice while an attempt was made to clear snow from it.

The Park District Risk Management Agency (PDRMA) often receives inquiries about what is a safe ice thickness. The caller is usually already aware of the unpredictability of ice and the judgment call that remains in front of them. The truth is that there is no guaranteed safe ice thickness. Different combinations of environmental and load factors do not allow for a sure-fire standard to be developed. The only way to eliminate the risk of accidentally breaking through the ice, is to close open-water venues to the public.

However, in the interest of tradition and winter-time recreation, the risk can be reduced through conservative approaches. Some agencies have already done this by establishing thickness benchmarks. A small study by the Bartlett Park District in 1991 indicated that ice thicknesses of four to ten inches were being used as benchmark measurements by survey respondents. However, a scientific equation for making objective calculations is probably a better option, and could replace "guesstimates" based on trial and error.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

According to the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, New Hampshire, ice is a material capable of supporting weight (a load), but ice is also affected by temperature, water quality, and other elements inherent to time and location. Following are a few of the more significant fluctuations that should be considered when making a decision about the safety of a specific site:

• Generally, the deeper the water, less ice is formed.

• Cold ice (or clear ice) is the first ice that forms; it has large columnar grains and is transparent. It is maintained at approximately 20° Fahrenheit (F) to 25°F or colder.

• Snow ice may form from saturating snow on top of cold ice; it has small grains. Snow ice is only about half as strong and melts quicker.

• Ice forms at 32°F and is always close to it's melting point. (By comparison, steel melts at 2,700°F).

• During warm periods, ice can melt from both the top and from the bottom. In fact, the water temperature below the surface can be warmer.

• Continuous walking (or skating) over ice will cause it to fatigue.

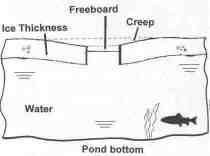

• Ice "creeps" or deforms over time even without an

18 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

SKATING ON THIN ICE

increase in load. (See diagram below.)

• Drilling a test hole enables you to check the "freeboard," or distance from the top of the ice sheet to the water. Water flooding up through the hole is a dangerous sign. (See diagram below.)

• Ice can be weakened by salt runoff and other impurities.

• Water current or velocity can reduce the thickness of ice especially near a spring or outlet.

HUMAN FACTORS

In illustrating the last point above, most of us are familiar with the opening scenes of the movie "It's A Wonderful Life." We remember the young George Bailey rescuing his younger brother, Harry, who has broken through the ice at the end of a sled run. (Or was that a coal shovel he was using?) It appears that the ice was too thin because of a natural outlet to a stream. In pulling the Baileys to safety, the other boys use the proverbial human chain to disburse their total weight over the unbroken, adjacent ice.

Load disbursement is a good principle, but it is not always practiced by skaters and vehicle operators on thin ice. Occasionally, skaters congregate, and their combined weight may suddenly be concentrated in a smaller area of the ice sheet. For example, during hockey play, many heavy skaters could surround the puck at one time or a group of youngsters could gather to admire a catch during an ice-fishing tournament. There are many possible scenarios.

AN EQUATION FOR REDUCING RISK

Hopefully a conservative ice thickness, that takes into account the site environment as well as possible load concentrations, has been estimated ahead of time. To calculate a conservative thickness, the CRREL recommends for cold ice, the equation h = 8 x &0214;t

Ö

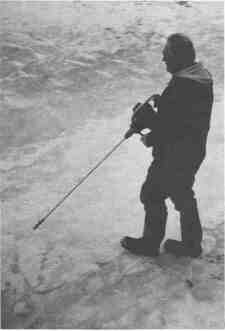

A Bartfett Park District employee drills a test hole to check the "free board." Photograph by Kevin Marks.

January/February 1998 / 19

FEATURE ARTICLE

Determining a safe thickness involves the use of a "worst case scenario" or the probable concentrations of persons/equipment in an area approximately 10 feet by 20 feet. However, this equation is subject to human error in that an employee could grab a heavier vehicle or forget to add the weight of an attachment. For this reason, it is generally inadvisable to drive heavy equipment or vehicles upon open-water ice.

LIABILITY

You may have noted that this article is peppered with words such as unpredictable, no guarantees, fluctuations, risk reduction, probably, unknown, possible, and the like. The truth still remains that even as we do our best in providing ice-related recreation, using open-water venues is still a judgment call and it boils down to individual discretion. To that end, agencies should formulate their own policy for determining a safe ice thickness, taking into account the particular conditions and uses of their open-water areas.

Developing an ice thickness policy will in fact help insulate an agency from liability. The Illinois Governmental and Governmental Employees Tort Immunity Act provides local governments with immunity for conditions of recreational property, except for willful and wanton conduct. Willful and wanton conduct is defined as "a course of action which shows an utter indifference to or a conscious disregard for the safety of others." How can an agency exhibit willful and wanton conduct when it has carefully considered its open water conditions and established an ice thickness policy for the safety of users? Best advice: be conservative in putting together your policy.

KEVIN MARKS

is the information Services Manager at the Park District Risk Management Agency in Wheaton, Illinois. He has a doctorate in Health and Safety from Indiana University as well as an Associate in Risk Management and an Associate in Automation Management.

20 / Illinois Parks and Recreation