|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

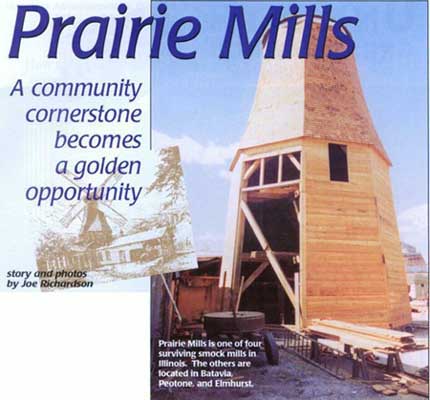

Absent the sails it looks like a misplaced lighthouse. An octagonal tower of yellow pine rising from the farmland in west-central Illinois. Since one side has yet to be reconstructed, wind cools the shell's insides. It rises and falls over dormant bits of mill — gears and spindles, sack traps and spurs — mixing century-old chaff with the dust of corn ground at a nearby elevator earlier this afternoon. For 60 years the millworks clicked and climbed and ticked overhead like the innards of an oversized clock. Grain rained from the upper decks and poured between pairs of ton-and-a-half millstones, where it was chewed into the beginnings of bread.

Outside, beyond the hiss and snap of cracking grain, above the chatter of farmers, merchants, children and wives, the mill sang. Its arms, 70-foot spans of wood and cloth — sails, they were called — pushed against the prevailing winds, carving sound from air. Together, mill and wind were elegant, inexhaustible, unstoppable. Or so it seemed. Changes came rapidly to Prairie Mills. Wooden blades replaced sail cloth. Combustion replaced wind. The blades, made useless by a gas-fired engine, came down and ornamental fans were put in their place. Even with modifications, Prairie Mills couldn't survive. With the advent of more sophisticated milling technology, the windmill at Golden fell silent. Over time, water sucked bits and pieces from the foundation and rotted the mill's legs and body. The cap — a 14-ton assemblage of wood and iron which swiveled the sails into the wind — bore down on the shell until the entire

10 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING • JANUARY 1999

mill tilted to the northeast. Like many of Illinois' early buildings, the windmill that had served as a center of community in Golden since 1872 seemed destined to become a memory. Then someone tried to buy it. Where there's a mill... "The problem was that the mill had been here for 125 years. It had become just another building," says Connie Louderback, president of the Golden Historical Society. "Many people didn't realize what a treasure it was." Louderback says attitudes shifted in 1985 when the village of Benson expressed an interest in purchasing the mill, disassembling it, and reconstructing it in their village park. Randy Kurfman, vice president of the historical society, agrees that the potential loss of a community cornerstone served as a wakeup call. "There were a couple of gentlemen in town who said: 'Wait a minute. We must have something here. If they want to tear it down and do something with it, maybe we can do the same thing.' They got on the phone, made some calls, and secured enough pledges to get a down payment to the bank." The Golden Historical Society was formed and restoration efforts launched shortly thereafter. Louderback says the society's major push for funding came in 1995 as a follow-up to Derek Ogden's assessment of Prairie Mills. The society located Ogden, an internationally renowned millwright based in Madison, Virginia, through SPOOM — the Society for the Preservation of Old Mills. The organization maintains a worldwide directory of mills, millers, and millwrights. Following Ogden's report, the Historical Society brought legislators and economic development groups through the mill and shared their plans for its future. It was an effective course of action. To date, the state has funded $300,000 of the restoration, contributing tourism grant matching funds and dollars from the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Kurfman says the funding added both emotional momentum and financial validity to the project. "When you start knocking on corporate doors and you have $350,000 toward a $450,000 goal, people will support you more than when you had $50,000 in the bank and were going for $450,000."

The remainder of the money secured by the society has been raised by what Louderback describes as "nickel and dime projects" — dinners, letter writing campaigns, door-to-door solicitations, memorial contributions, and through sales of Prairie Mills memorabilia. While the society reached its financial goal of $450,000 last year, the money fell short of the mark in terms of renovation. The first phase of the project, which includes renovating the shell, refurbishing the cap, and replacing the blades, is expected to cost about $200,000 more than the original estimate. "The problem is, if we try to take one section out, there's no place to stop," Kurfman explains. "With a house you can take a section out and rebuild without losing the entire structure. We basically have a shell. It's like a big set of Lincoln Logs. If you take one piece out, the whole thing goes." The obvious option, tearing the mill apart and rebuilding it from the ground up, wasn't pursued because so much of the internal machinery — an estimated 75 percent — has hung intact and virtually unchanged for 125 years. In order to preserve the integrity of the mill-works, the society opted to shore up the skeleton with steel beams and cribbing and replace the rotted framework a piece at time. Add rising material costs and additional reconstruction to the formula, and you run into a budget deficit.

JANUARY 1999 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING 11

"The other problem is that there was no foundation," Kurfman adds. "With a house you have something solid to build on. This had limestone piers under each of the eight cant posts (legs which support the mill's walls) and creek gravel that served as the other part of the foundation." Now each cant post locks into a sill plate which rests on a foundation made of concrete and brick. In keeping with generally accepted renovation practices, the Golden Historical Society has worked to maintain as much of the

12 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING JANUARY 1999 original structure as possible while restoring the structural integrity of the mill. One of the few historical sleights of the hand performed by the society will involve the mill's new blades. Contractors will use a tubular steel stock which is both lighter and more durable than wood. At present the blades, which are easily the most striking feature of the mill, are on hold until the society can find additional funding. Louderback says other details of the mill's future are still being hammered out, but long-range plans may include transforming Prairie Mills into an interpretive site with guides in period dress, landscaping, and a prairie plot behind the mill. "We would have enough staff, products, and services so that people could actually see the grain being ground," she says, "and a good story line could go along with it." Louderback, who teaches junior high classes at a nearby school, says it's important that today's kids see what their forefathers did to make a living. "Part of what they are has developed through things like this. We're interested in preserving not only the building itself," says Louderback, "but the craftsmanship, the engineering, the ideas, and the thinking. All those things are going to be preserved here." Kurfman says the society is targeting 1900 to 1910 as the era it wishes to recreate. "We're looking at that time frame because we can document it extremely well with photographs, and there are also written records that we can look back on from that time." Trade Winds While both Louderback and Kurfman say Prairie Mills is worth saving simply for the sake of historic and cultural preservation, they also hope it will reestablish itself as a significant part of the Golden area economy. "We've got the potential for a lot of tourist traffic. We're directly in the middle of Mormon history," Kurfman says, referring to the Mormon settlement at Nauvoo. "We're an hour and 45 minutes away from Springfield, and Hannibal (Missouri) is less than an hour away." Kurfman says the society has already targeted a number of niche markets. "We're going after the motorcoach market, and Quincy has an excellent convention and meetings market," he says. "There are things like spousal tours, side trips, and bank clubs looking for day trips. Plus we'll have to take a strong look at what we're doing right now with the current festivals. We may want to revamp those and center more around the mill to really enhance the attendance of what we're doing. "You've got a unique opportunity here," he adds. "This mill is one of four left in the state of Illinois, yet it's one of only a handful left in the United States that is still operable. We have a unique opportunity to teach a forgotten way of life."

30 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING JANUARY 1999 |

|

|