|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

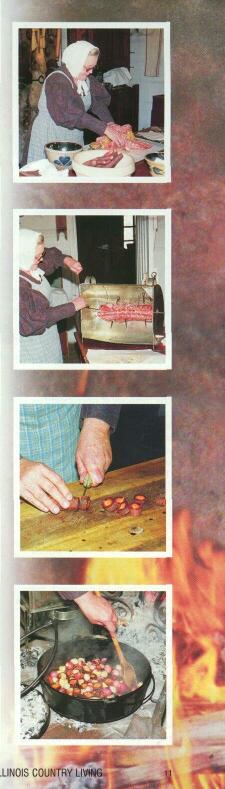

Wood crackles on the open hearth as Barbara Archer, period interpreter, rolls out biscuit dough. A pork roast is stuffed with apricot and onion dressing, and skewered in a rotisserie-like "reflecting oven" beside the fire. A medley of vegetables and a bowl of applesauce bubble as the heat cuts through them. A buttery, cherry-filled pie rests beside the vegetables, perched over hot coals. The students are dazzled by the "magic" of her cooking methods. Barbara gently nudges the charred wood with a poker, then she turns to the students and says, "Welcome to the Rutledge Tavern! For 37-1/2 cents a day, travelers in the 1830s could come here for a warm meal and a place to sleep." Barbara and her husband Bill have been volunteers at New Salem since 1989. Together, they've been involved in an assortment of activities, such as cooking, spinning, weaving, quilting, gardening, sewing, rug hooking, candle making and blacksmithing. "We really enjoy spending time out here doing just about anything," says Barbara. "But from the beginning, my favorite period interpretation has been open-hearth cooking." She admits that she didn't know much about it when 10 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING www.aiec.org

she first began, but says she fell in love with the challenge of it. "It was all a learning process," she says. "I learned by doing research and by going to other historical sites and cooking with people who knew how it was done." Barbara says it was a big adjustment to know what ingredients would have been used back then, and to know how hot your "stove" is since there is no pre-heating or temperature setting for a fireplace. "Every time I cook, it's trial and error. I've gotten the feel for how to cook certain foods. And even though I've been doing this for 13 years, I still burn things occasionally. But when I get it right, it's the best meal you'll ever taste," she proclaims. Fire, it has been said, is the metaphor for life. But back in the 1830s, Bill says, it was a means of survival and a way of life. "When people would enter a home back then, they would naturally go to the fire," says Bill. Fire represented the trinity of light, warmth and food. In today's times of light bulbs, thermostats and electric ovens, it's impossible for people to appreciate the importance of fire in the lives of pre-industrial people. Barbara says, today a woman can work all day, and still come home and create a nice meal for her family in less than an hour. "But back then, women would traditionally begin cooking when the sun came up and have dinner ready at noon." She says they'd spend the rest of their day cleaning up and doing chores. Then supper would be leftovers from the noonday meal. "Traditionally dinner was a one-pot meal, such as corn chowder, ham and beans, potato soup, fish chowder or barley soup," Barbara says. "The only time they would really cook a full meal was for a special occasion, like when the militia met every summer and fall. And it would be a village meal where the women would all cook for an entire week," she says. But for Barbara, cooking over the open fire is not a chore at all. "I love the taste of a fire-cooked meal," she says. "I can cook an entire Thanksgiving dinner over the hearth easier than I can at home now. I've found that I've been doing this so long that sometimes things I cook using modem conveniences don't turn out nearly as good." Although, she says, anything you can cook over the fire can be cooked in your own kitchen. "If I'd cook something in a hanging pot, you could cook it on your stove top. If I'd cook something in a baking kettle, you could cook it in an oven. If I'd cook something in a roaster, you could cook it on a

June 2002 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING 11

charcoal grill," Barbara says. Barbara was so interested in the methods of open-hearth cooking that she began researching and collecting cook books. "I would sit down and read a period cookbook like a normal person would read a novel," she says. Then in 1999, she decided to put her research to good use and she began creating her own cookbooks. "I actually have three books out, but only two are period." The first one is called "Simple Fixin's," and it's filled with pre-1840 recipes including breads and one-pot meals - both vegetable and meat-based. Barbara says she tried to fill this book with recipes that would have been very common to the people of New Salem. "I chose a recipe for fish chowder because they would have had access to plenty of fish from the river. At that time, shrimp gumbo wouldn't have been too likely," she laughs. And though some period recipes she came across were very tempting to use, she had to restrain and only use recipes with ingredients that were plentiful to the New Salem village. "People of that time period would have definitely made banana bread, but in order for the people of New Salem to access bananas, they'd had to have been shipped from the Ohio River to the Mississippi River and then to Havana," she says. "They weren't an easy commodity to get." Barbara admits, "Some of the recipes in my 'Simple Fixin's' book have been modified a little to fit today's tastes and health standards." People don't cook with as much salt or fat anymore and Barbara says modifying the recipes doesn't hurt the taste any, just makes them healthier. "Also, people of that era were very poor and would cook with things they could grow or get easily. Not too many people today would enjoy the taste of dandelion greens, but those were a very common source of food at that time," she remarks. "My second period book is not a recipe book, but rather an herb guide called 'A Kitchen Garden Primer,'" she says. While she was researching her hearth cookbook, it became obvious to her that herbs were a very essential part of that period of cooking. She soon began planting and finding different ways to use the various herbs. "Many of the new volunteers didn't know what to do with some of the herbs we planted, so this book really started out as just an interpreter's guide, but it was so popular, I was asked to publish it." In this book, you will find uses for the most unique to the most traditional herbs used to bring out the flavor of hearth-cooked dishes. In addition to planting a large herb garden in the summer months, Barbara and Bill also keep busy planting a vegetable garden. "We like to plant vegetables that you wouldn't find every day," says Bill. "When was the last time you tried a white radish,

12 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING www.aiec.org a scarlet carrot or salsify (a vegetable that tastes like oysters)?" Barbara adds, "It's always fun to cook with vegetables that spark curiosity and questions." Some of the other vegetables you could expect to find in the Archers' garden include several different kinds of lettuce, turnips, parsnips, squash, cucumbers, eggplant, celery root, tomatoes and peppers. "Most people in those days had what they called a kitchen garden, which included a variety of vegetables, some fruits and herbs," says Barbara. The Archers spend about 1,050 hours a year volunteering at New Salem. Along with the many other volunteers at the park, they spend their free time bringing life to the past. In an instant, they'll transport you to a simpler time - a time before television, CD players and computers. A time that you soon will learn was not all that simple. They create a living history book, open for all to study. "It's been such a great experience for the both of us. And as far as I'm concerned, there's no better satisfaction than looking into someone's eyes when they realize history is still alive," says Barbara. If you are interested in becoming a volunteer at New Salem, contact Betty Ackerman at (217) 632-4000.

June 2002 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING 13 |

|

|