|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

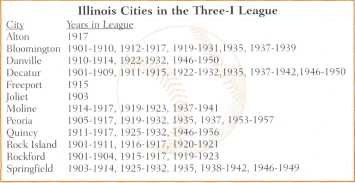

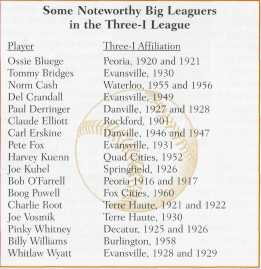

Minor-league miracles by Bill Steinbacher-Kemp Minor league baseball stands as one of the more overlooked chapters in American sports history. In the decades before World War II, the minors dominated the sporting life of communities throughout the nation. "Long before urbanization, expansion, and the electronic media focused mass attention on the big leagues, the minors formed the core of baseball activity in cities and towns throughout the nation," noted Lawrence S. Katz in a 1990 article in the Baseball Research Journal. In downstate communities such as Bloomington, Danville, Decatur, Peoria, and Springfield, baseball fans enjoyed a front-row seat to one of the nation's oldest and more celebrated minor leagues. For six decades, the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League (also known as the "Three-I," "Three Eye," or even the "Triple Orb") was a national force in minor league baseball. Organized in 1901, the Three-I was a class B minor league, the highest level of the "low minor leagues" (B, C, D and E). Throughout its storied history, the league was nationally recognized as a wellspring of Major League talent.

Bloomington, Cedar Rapids, Davenport, Decatur, Evansville, Rock Island, Rockford, and Terre Haute completed the inaugural season. The Hottentots of Terre Haute claimed the league's first pennant with a record of 72 wins and 39 losses. Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown pitched for the championship club, finishing with 23 victories and 8 defeats. The fourth-place Rockford Red Sox featured two future big leaguers. Outfielder Davy Jones played three seasons for the Chicago Cubs and seven for the Detroit Tigers. Righthanded pitcher Claude Elliott led the Three Eye in strikeouts (297) and earned run average (3.13) while winning 26 and losing 11. In 1905, Elliott, under the tutelage of the famed New York Giants skipper John McGraw, became the big league's first relief specialist. Rockford captured the league title in 1902, and the Bloomington Bloomers claimed their first of four championships the following season. Evansville (known at one time or another as the River Rats, Evas, Pocketers, Hubs, Bees, and Braves), claimed a league-best eight pennants. Bob Coleman, arguably the most influential figure in Three-I League history, managed all eight championship clubs. Coleman's 37-year managerial career also included stops in Terre Haute, Decatur, and Springfield. Throughout its sixty-year history, franchises constantly folded or moved, sometimes in midseason. During the 1903 campaign, for instance, poor attendance prompted the Joliet Standards to relocate to Springfield where the club became the Foot Trackers. Even natural disasters played a role in the league's ever-shifting roll call. In the 1916 season, Decatur for-feited its franchise because a tornado blew off the roof of its ballpark grandstand. Hannibal, Missouri, then replaced Decatur, and the Mules earned a second place finish with a 79-57 record, 6 games behind the pennant winning Distillers of Peoria. For extended periods in its history, the league's name was a misnomer. From 1922 through 1936, there were no teams from Iowa. The early history of the Three Eyfl is best illustrated through the lives and careers of the men who played in the league. Bob O'Farrell and Ossie Bluege were two successful Three-I League veterans. Both were born and raised in Illinois, both played for Peoria, and both enjoyed long and productive big league careers. Born in Waukegan in 1897, Robert Arthur O'Farrell was a prep star of some renown who also played in the semi-pro Lake Shore League. In 8 | Illinois Heritage 1915, Chicago Cubs owner C. Webb Murphy signed the teenage phenom to a big-league contract. "[W]hen I was finishing high school, I was just as rabid a White Sox fan as ever," O'Farrell recalled in Lawrence S. Hitter's oral history The Glory of Their Times (1984). "I was catching for the local Waukegan semipro team then, and one day in the middle of the summer we played an exhibition game with the hated Chicago Cubs. Well, lo and behold, after the game the Cubs offered me a contract! I grabbed it up, and suddenly, after all those years of being a White Sox fan, there I was, of all things, a Cubs fan!" As one of four catchers on the Cubs roster (including player-manager Roger Bresnahan), O'Farrell had no chance of breaking into the everyday lineup. After riding the bench for most of that year and the start of the next, the Cubs shipped the teenager to the Three Eye. In two seasons in Peoria, O'Farrell batted .286 and .318 respectively. Charlie Hollocher, the future big-league shortstop, also played for Peoria during this time. O'Farrell and I lollocher later roomed together when they were teammates in Chicago. Tragically, 1 lollocher's promising career was cut short due to a nervous condition, and he committed suicide in 1940. Top of the First On April 6, 1917, the U.S. declared war on Germany, and tens of thousands of men enlisted or found employment in wartime industries. That summer, low minor leagues throughout the nation succumbed to the manpower shortage, and on July 8, the Three Eye suspended play. That same day, South Bend of the Central League relocated its franchise to Peoria, and O'Farrell remained in the city to play Class B baseball, albeit in another circuit. At the end of the season, he was back with the Cubs, this time to stay. In Eugene Murdock's 1991 oral history Baseball Players and Their Times, O'Farrell recalled his playing days in the Three Eye. "Well, we didn't live very high. We traveled on those old 'rattler' trains, you know. The towns weren't too far apart so we traveled mostly in the daytime, but it was hot. Really brutal, but I didn't mind that much. We were all young and I was so glad just to be playing ball. I would have played for nothing, if it had to be that way.... Ball parks were not much. They were wooden and seated a couple of thousand people, maybe. But they were good enough for that level of play."

In 1918, O'Farrell appeared in 52 big league games (45 behind the plate), sharing catching duties with veteran Bill Killefer. "Those were the days when catching was really rough," he remembered in The Glory of Their Times. "There were so many off-beat pitches then, you know. Like the spit-ball, the emory ball, the shine ball. You name it, somebody threw it." In 1924, a foul tip shattered O'Farrell's mask, knocking him unconscious and fracturing his skull. The following spring, Chicago sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals, and in 1926 he enjoyed his finest season, earning National League MVP honors for the World Series champion Redbirds. O'Farrell played a key role in the epic 1926 World Series against the New York Yankees. In the deciding game seven at Yankee Stadium, the Cardinals were ahead 3-2 in the bottom of the ninth inning. As the Yankee faithful roared their approval, Grover Cleveland Alexander walked Babe Ruth. With two outs and Bob Meusel at the plate, Ruth attempted to steal second base. O'Farrell fired the ball to second baseman Rogers Hornsby, and Ruth was out by a wide margin. The Cardinals had won their first World Series. In 1938, O'Farrell returned to his minor league roots and led the Bloomington Bloomers to a disappointing seventh-place finish in the Illinois Heritage 9 eight-team league. The previous season, the Bloomers struggled at the gate and folded in early July. With O'Farrell at the helm and an agreement with Milwaukee of the American Association to support the struggling franchise, there were high hopes for the Bloomers. Yet hy the following season, O'Farrell was gone and Bloomington, one of the leagues founding members, was playing its final season in the Three Eye. "I did get a little discouraged at times, but I guess you do in any job," reflected O'Farrell. "Of course, when you play every day it gets to be sort of like work. But, somehow, way down deep, it's still play. Just like the umpire says: 'Play Ball!' It is. It's play." O'Farrell died on February 20, 1988, in Waukegan.

Born in 1900, Oswald Louis Bluege played baseball on the streets and sandlots of Chicago, studying under local legend Charley Pechous, a third basemen who played briefly for the Chicago Whales of the Federal League and afterwards the Cubs. Bluege and his younger brother Otto played ball for St. Mark's Lutheran Church and Schurz High School. Ossie Bluege reminisced about his early years in Donald Honig's The Man in the Dugout: Fifteen Big League Managers Speak Their Minds (1977). "I was going to school at night, taking accounting courses, and holding down a job during the day with International Harvester," he recalled. "Through a fellow named Jack Doyle, an ex-major leaguer, I started playing some pretty fast semipro ball around Chicago. I was getting fifteen dollars a gameó not bad money in those days." Bluege's semipro career also included a stint with Jimmy Callahan's Logan Squares, a barnstorming outfit of some fame. In 1920, Bill Jackson, the owner of the Three-I League's Peoria franchise (renamed the Tractors), offered the gifted infielder a $200-a-month contract. Bluege promised his strict German father that if he didn't make the big leagues in three years, he'd finish school and begin a career in accounting. After his father grudgingly consented to the plan, Bluege signed the contract. "The next day I caught the night train to Rock Island [the Tractors were in the Quad Cities to play the Moline Plowboys] and got there at four in the morning,' Bluege recalled. "I checked into the hotel, slept a few hours, and at 7:30 was up and ready to go. That was my normal routineóget up early and go to work. I hung around the lobby until nine o'clock, and nobody had showed up. What is this? I asked myself. So 1 rang Jackson's room and told him I was there. 'What the hell are you calling me up at this hour of the morning for?' he asked. 'It's time to go to work, isn't it?' I asked. That's when I began to get the idea that this was going to be a different life." Chuck Dressen (who would later play for Cincinnati and enjoy a long managerial career) was the everyday third baseman, so Bluege shifted to shortstop. In his first season of professional ball, Bluege appeared in 45 games, batting .286. He returned to Peoria the next year to hit .293 in 140 games.

For eighteen seasons (1922-1939), Bluege patrolled the infield for the Washington Senators, becoming at mid-career one of the more accomplished third basemen in the majors. Bluege played for three pennant winners, including the 1924 club that defeated John McGraw's New York Giants. He remained loyal to magnate Clark Griffith, serving as Washington's coach (1940-1942), manager (1943-1947), and farm director (1948-1956). He then acted as comptroller (1957-1971) for the Senators and Minnesota Twins. During the darkest years of the Great Depression, the Three Eye lacked the resources to maintain a viable circuit. The league folded in the middle of the 1932 season, and suspended play the following two years. The 1935 season featured six clubs (Bloomington, Decatur, Ft. Wayne, Peoria, Springfield, and Terre Haute), and although the league managed to complete a full split season, it was unable to continue operations in 1936. Still, the league featured an array of big league talent. For example, during the 1932 season, the Decatur Commodores ("Commies" for short) pitching staff featured Elden Auker, Dutch Leonard, and Claude Passeau. All told, they would combine for 483 big league wins. Though the three righthanders enjoyed productive big league careers, they were a combined 10-15 in the Depression-shortened 1932 season. Not long ago, Baseball America writer Jim Callis ranked this staff the sixth greatest in minor league history. Obviously, Callis based his rankings not on minor-league perform- ance but on big-league productivity. In 1935, Burleigh "OF Stubble-beard" Grimes arrived in Bloomington to act as player-manager for the Bloomers. Prior to his arrival in the Three Eye, Grimes was one of the finest Major League pitchers of his generation, notching 270 career 10 | Illinois Heritage  victories in 19 seasons. When he retired in 1934, Grimes was the last hurler to legally throw the spitball. In 1920, Major League Baseball outlawed the controversial pitch, though seventeen practicing spitballers were granted a lifelong exemption from the ban. Grimes, who was only twenty-six at the time, continued to use the spitball, though he maintained that "loading up" was effective only in combination with other pitches. Famed Cardinals executive Branch Rickey convinced Grimes to relocate to Bloomington, a move that both hoped would prolong his playing days and launch a managerial career. Not everyone, though, greeted the wily pitcher with open arms. An April 1, 1935, article in the Bloomington Pantograph noted that Decatur manager Johnny Butler initially opposed the reintroduction of the spitball to his league. In the first half of 1935, Bob Coleman's Springfield club finished first, several games ahead of Bloomington. In the second half, the league's top two teams switched place, with the Bloomers besting the Senators. Grimes played a prominent role in the club's success, winning ten of his last fifteen decisions. The two clubs met in the league's post-season playoff, and although Springfield led the series 4-2, Coleman's refusal to replay a contested game forced the league president to declare Bloomington the winner. From the relative obscurity of the Three-I, Grimes returned to the bright spotlight of the big leagues. For two seasons (1937-1938) he managed the Brooklyn Dodgers, concluding his brief tenure with an unimpressive .432 winning percentage (130-171). The cantankerous Grimes struggled under the accumulated weight of shortstop Leo Durocher's disaffection and first base coach Babe Ruth's disinterest. After the disappointment of Brooklyn, he returned to the minors to coach for another decade. Bottom of the Ninth The end of World War II proved a boon to minor league baseball in the United States. In 1945, there were a dozen minor leagues in the nation. Four years later, there were a record 59 leagues in 448 communities. During this period, the Three Eye enjoyed relative stability. In 1947, Waterloo drew a single-season club record of 174,000, and three years later, the league set an all-time attendance record of almost 783,000. A July 15, 1950 Collier's article by Tom Meany hailed the Three-I League as "the symbol of the bushes." Entering its sixth decade of operation, Meany noted that the league's talent pool remained impressive. He estimated that at the start of the 1950 season, there were fifty Three-I League veterans earning paychecks on the Major League level, including Birdie Tebbetts (Springfield, 1935), Dizzy Trout (Terre Haute, 1935), Dick Sisler (Decatur, 1941), and Allie Reynolds (Cedar Rapids, 1941). During this era, the strength of a minor league was dependent on the strength of the parent clubs. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the big league powerhouses were represented in the Three Eye. During this time, Danville was an affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Decatur received much-needed backing from the St. Louis Cardinals, and Evansville enjoyed a profitable relationship with the Boston-Milwaukee Braves. In addition, Terre Haute provided several key players to the 1950 pennant winning Phillies (dubbed the Whiz Kids), and Waterloo was an affiliate of the Chicago White Sox during the early "Go-Go" era.

No one ever made a fortune in the Three Eye, even during the gravy days of post-World War II affluence. In 1950, teams were limited to seventeen players, and there were few dollars for superfluous office and clubhouse personnel. "There are no coaches, road secretaries, team physicians, baggage handlers, or any of the multitudinous refinements of the majors," reported Meany. "Terre Haute is unique among the Three-Eye clubs in that it has a trainer, Casey Bruzas, but he also doubles as the bus driver." In 1950, Three-I payrolls averaged $4,000 a month, or roughly $325 per player, though assistance from Major League clubs boosted the pay of some players. In the 1950s, with competition from television and the manpower drain of the Korean War, minor leagues throughout the nation began folding. Yet under the direction of legendary Chicago sports broadcaster Hal Totten, the Three-I League survived into the early 1960s. Regrettably, Totten could not forestall the inevitable shakeup of competing Midwest leagues. As the Three Eye weakened during the late-1950s, several leading franchises shifted operations to the Class D Midwest League (known previously as the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League). Waterloo left the league in 1956 and Davenport in 1958. With the end approaching, the league limped along, a shadow of its storied past. In the final years, teams from Kansas, Minnesota, and Nebraska, joined the Three Eye, Illinois Heritage 11 making the league's name an anachronism from times gone by. The Three-I League suspended operations after the 1961 season, and the nation's oldest Class B loop was no more. Yet during its waning years, the league boasted of some first-rate talent, including Frank Howard, who played for Green Bay, and Earl Weaver, who acted as a player-manager for Fox Cities. The Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League dates to a time when baseball mattered. Before the ascendancy of professional football and basketball, baseball was for many Americans the only game in town. In the first half of the twentieth century, "America's Pastime" was more than a hollow marketing slogan. During that time, the Three Eye played a noteworthy (though underappreciated) role in the game, both on the minor and big league levels.

In 1930, Tommy Bridges appeared in 20 games with the Evansville Hubs, winning 7 and losing 8. Yet before the season was over, the 23-year-old righthander earned a promotion to the Detroit Tigers. On August 31, he appeared in his first Major League game, a Yankees blowout in New York. The Bronx Bombers had tagged Tigers pitching for 13 hits and 10 runs in less than 5 innings. In the sixth inning, manager Bucky Harris ordered Bridges to the mound. The first three batters Bridges faced in his big league career were future hall-of-famers Babe Ruth, Tony Lazzeri, and Lou Gehrig. The unproven rookie was so nervous that he threw a warmup toss right over the head of catcher Ray Hayworth. Having seen enough, plate umpire Bill McGowan summoned the Tigers newcomer for a talk. Years later, Bridges recounted the one-way conversation in Ira Smith's Baseball's Famous Pitchers (1954). "Listen, son, you threw the ball past bats in the Three-I League that are just like the ones these fellows up here have in their hands," said McGowan. "And you're bound to do better than those two guys who were in here pitching before you. So just figure it's only another ball game and do your best. Luck to you." Ruth then hit a pop fly to right field, Lazzeri chopped a base hit through the infield, Gehrig struck out, and Harry Rice (another product of the Three Eye) grounded weakly to third. Although Bridges gave way to a pinch hitter in the seventh, he was well on his way to a successful big league career. In 16 seasons with the Detroit Tigers, Bridges appeared in 424 games (362 as a starter), falling 6 short of the 200-win mark. After baseball, Bridges struggled with alcohol. In his rewarding 2001 memoir Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms, big league pitcher and Three-I veteran Elden Auker reminisced about his former teammate. "Every time I see one of those T-shirts you see nowadays, the ones that say, 'Baseball Is Life,' I think of Tommy Bridges. Baseball was everything to him. I guess once he could smell the end of his playing career on the horizon, the scent of liquor was the only thing that could kill that frightening odor."

12 Illinois Heritage |

|

|