|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

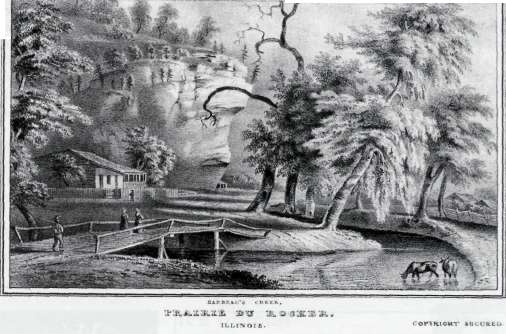

By R. Bruce McMillan  The road that parallels the bluffs between Prairie du Rocher and Modoc in Randolph County, a region rich in French Colonial history, is the same route that linked the French settlements of Kaskaskia and Cahokia prior to statehood. Southeast of Prairie du Rocher, a late-eighteenth-century traveler would pass the settlement's common field before entering a large bottomland prairie, known locally as the Grand Prairie. Here a traveler would cross Rarbeau Creek, named for Jean Raptiste Barbeau, a leading citizen of Prairie du Rocher, who had built his French colonial house at this location. Barbeau's residence, located back from the creek, was well protected by the towering bluffs that wall the valley from the adjacent uplands. It is this location that is featured here—a scene that was captured in an 1841 lithograph by John Casper Wild entitled Barbeau's Creek, Prairie du Rocher, Illinois, pictured above. The road that parallels the bluffs between Prairie du Rocher and Modoc in Randolph County, a region rich in French Colonial history, is the same route that linked the French settlements of Kaskaskia and Cahokia prior to statehood. Southeast of Prairie du Rocher, a late-eighteenth-century traveler would pass the settlement's common field before entering a large bottomland prairie, known locally as the Grand Prairie. Here a traveler would cross Rarbeau Creek, named for Jean Raptiste Barbeau, a leading citizen of Prairie du Rocher, who had built his French colonial house at this location. Barbeau's residence, located back from the creek, was well protected by the towering bluffs that wall the valley from the adjacent uplands. It is this location that is featured here—a scene that was captured in an 1841 lithograph by John Casper Wild entitled Barbeau's Creek, Prairie du Rocher, Illinois, pictured above.

As it turns out this bluff overhang would become famous in the 1950s, when the Illinois State Museum made one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the twentieth century under this overhanging bluff. Fortunately, a Museum photographer snapped a photograph in 1953 that almost duplicated the perspective provided by Wild in his image. Road construction crews had borrowed sediment for fill from beneath the overhanging bluff, and in the vertical exposures left by the highway workers, ash lenses and other signs of human occupation were clearly revealed. Excavations by the Museum demonstrated that buried beneath this bluff—throughout 25 feet of sediment—was a record of human occupation that spanned most of the Holocene, representing the past 10,000 years. At the time, there was no other location in eastern North America that had such a complete record of Native American occupation. The resulting study of the changing adaptative patterns of hunting and gathering peoples to their environments through time in the Mississippi Valley, became a landmark in the annals of American archaeology. The Museum returned to the site in the 1980s and carried out additional excavations, work that was summarized in The Living Museum, Vols. 45(1) and 53(1). The purpose here in presenting two "snapshots" of Modoc Rock Shelter, produced a century apart, is to stress the value of images taken at different times at a specific geographic location. "Paired" images are especially useful when studying landscape history and assessing change in the natural and built environments. Although one has to be careful when utilizing the works by artists in their portrayal of reality, there is often information that can be gleaned from early landscapes recorded as sketches, paintings or in lithographs. For example, W. Raymond Wood, a professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri, has carefully photographed many of the landscape scenes along the upper Missouri River in Montana that Karl Bodmer sketched in 1833 and later produced as aquatints. Wood has found that Bodmer's perspectives were executed with such accuracy that he is able to replicate many of the same scenes with his camera 150 years later, but with noticeable changes in vegetation cover. Similarly, modern photographs taken at the same locations as earlier historic photographs provide useful comparative 6 Illinois Heritage

information. For example, photographs taken by William H. Illingworth in 1874 as part of the Black Hills "Custer" Expedition, when compared with modern photographs, show the vegetation in the Black Hills in South Dakota has changed dramatically since the advent of fire suppression. These "paired" photographs can be viewed on a Web site that describes the expedition (see http:/www.custerstrail.com/). The lithograph of Modoc Bock Shelter with Barbeau Creek in the foreground was published in 1841 in a book entitled The Valley of the Mississippi Illustrated in a Series of Views by J. C. Wild and edited by Lewis Foulk Thomas. The photographic image of the shelter that replicated the earlier image was taken in 1953 by a Museum photographer and gives a strikingly similar perspective to that provided by Wild. Contrasting the two images, there are a number of observations that one can make. The meandering

stream depicted by Wild, while romanticized, shows the creek curving so that it flows more or less parallel with the bluff. This course is borne out by modern aerial photographs where there is still evidence of the original channel. The 1950s photograph no longer shows this meandering course because prior to the time of this photograph, the stream had been channelized and straightened into a drainage ditch. The cornfield that borders the road also demonstrates that modern agriculture has transformed what was once bottomland prairie. Another noticeable change is the vegetation on the bluff crest. In the 1841 image red cedars are shown near the top of the vertical cliff face but not beyond. The loess slope immediately above the cliff exposure is a hill prairie, almost certainly dominated by little bluestem. When one views this same location in the 1950s photograph, the grasses and forbs have all but disappeared as the cedars have encroached on this small hill prairie. This no doubt reflects the suppression of the periodic fires that kept these small prairie patches free from woody species. One also notices a small framework or structure built beneath the rock shelter. This is consistent with the use of the sheltered areas along these bluffs by the early settlers. Even today farm implements, hay, posts, and other farming equipment are stored beneath these shelters. Finally, Barbeau's French Colonial residence, illustrated in the lithograph, has been replaced or modified, and in its place at the exact location is a two-story farm house.

The road that parallels the bluff is the same route that was shown by Wild; for that matter, it is the same trail recorded by Thomas Hutchins in 1771 on a map reproduced by the Illinois State Museum in an atlas entitled Indian Villages of the Illinois Country compiled by Sara Jones Tucker. All in all, these two images show both change and continuity in the landscape at "Barbeau's Creek at Prairie du Rocher." Modoc Rock Shelter is listed today as a National Historic Landmark. The site is owned by the Illinois State Museum and can be seen by driving the bluff road two miles southeast of Prairie du Rocher. Even today, if one stands at the bridge over Barbeau Creek, many of the landmarks shown in J. W Wild's 1841 lithograph are still recognizable. For those interested in the archaeology of Modoc Rock Shelter, publications are available through the Museum R. Bruce McMillan is Director Emeritus of the Illinois State Museum and a long-time member of the Illinois State Historical Society. *Reprinted by permission of the Illinois State Museum, the Living Museum, Vol. 67, No. 1, 2005, pages 4-5.

8 Illinois Heritage

By Owen W. Muelder Galesburg and Knox College, located in west central Illinois, were founded in 1837 by anti-slavery advocates who came to Illinois from upstate New York. The town and college were perceived as a center of abolitionism and Underground Railroad activity in Illinois. Though other downstate communities could lay claim to significant anti-slavery and Underground Railroad involvement, Galesburg was unique. The overwhelming majority of citizens, at least for the first twenty years of its existence, were opposed to the institution of slavery. On July 4, 1837, the Galesburg colony organized a local anti-slavery society, and, in April of 1839, they established a Youth Anti-Slavery Society. In Knox County, the most celebrated Underground Railroad incident unfolded in the fall of 1842. A fugitive slave named Susan Richardson, the property of Andrew Borders of Randolph County in southern Illinois, fled north. Though Illinois was technically a "free" state, slavery existed in several southern counties for years, many from the time the French first occupied the region. Borders had a reputation for harsh treatment of his slaves and one day, after a disagreement between Susan Richardson and his wife, Richardson fled north to freedom that night taking her two young children, her older half-grown son, and another enslaved woman named Hannah. Richardson fled to the home of William Hayes, a known anti-slavery man who lived close to Borders' homestead. The five fugitives, with Hayes as their guide, fled north on September 1, 1842. On September 6, having slept the night before near Farmington, Illinois, they were carried by Underground Railroad conductor Eli Wilson into Knox County, and conveyed to the residence of the Reverend John Cross in Elba Township. Illinois Heritage 9

But on their way to Cross's home they were spotted, and later found hiding in his cornfield. The fugitives were incarcerated in the Knox County jail. When Borders learned of their whereabouts, he came to Knoxville, then the county seat, to claim his property. But local abolitionists came to the fugitives' defense, arguing that Borders could not prove these people were his slaves. Consequently, Borders was forced to return to Randolph County to get papers to verify his claim. In the meantime, the fugitives were released from jail by the sheriff on condition that they remain in the area. Susan Richardson found employment doing laundry and her oldest son found work doing chores on a nearby farm. A day after Richardson moved into her own place, Borders and his son returned to Knoxville. The sheriff, Peter Frans, helped round up Richardson's children, assuming with Borders that their mother would surrender herself when the children were in custody. But local friends talked Richardson out of giving herself up— a wrenching decision—and on a snowy night she was disguised and spirited off to Galesburg in a sleigh. After months of legal wrangling that involved prominent citizens such as George Washington Gale and Nehemiah West, who spoke on Richardson's behalf, Borders returned to southern Illinois with the children. Susan Richardson eventually took up permanent residence in Galesburg, joined the Old First Church, helped found the first black church in town, became involved in the Underground Railroad operation, and remained in the community for nearly sixty years— but she never saw those children again. Richardson moved to Chicago in the early 1900s and lived with a daughter from a subsequent marriage. She died in 1904 and was buried in Hope Cemetery in Galesburg. In 1846, Jonathan Blanchard arrived in Galesburg from Cincinnati to become the second president of Knox College. Before moving to Illinois he had already established himself as an anti-slavery crusader. Shortly after moving to Galesburg,  The home of Galesburg and Knox College founder George Washington Gale, who helped define northwestern Illinois' atttitudes toward slavery. 10 Illinois Heritage

Blanchard and Susan Richardson helped plan the escape of fugitive slave Bill Casey. Casey, exhausted and miserable, appeared at Richardson's house one evening. The following day she enlisted the aid of Blanchard, Nehemiah West, and Abram Neely to move the runaway slave to the next station on the "Railroad." Before Casey left Galesburg he was given fresh clothing and a new pair of shoes. One of the most important Underground Railroad "depots" in Galesburg was the home of Samuel Hitchcock, who lived just west of where Galesburg High School stands today. In Charles C. Chapman's History of Knox County, the following incident is record:

Numerous runaway slaves were ushered north out of Galesburg, up through Henry County into Geneseo, and up the Rock River towards Wisconsin and Lake Michigan. Another escape route out of the college town sent freedom seekers through Stark County and then into Bureau County, where runaway slaves made their way to the home of Owen Lovejoy, brother of martyred abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy, who lived in Princeton. Fugitives were then moved through the secretive and illegal Railroad network to hideouts in and near Chicago before moving safely to Canada, where fugitive slave laws did not exist. In Galesburg on October 7, 1858, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas held the fifth of their seven debates, as part of their campaign race for a seat in the United States Senate. The primary issue at these debates was the extension of slavery and whether it should be allowed in the nation's western territories. Given the town's and college's anti-slavery heritage, Lincoln knew full well that he would be speaking before a sympathetic crowd that afternoon. The Galesburg debate, held on the east side of Old Main at the Knox College campus, was the first in which Lincoln condemned the immorality of Douglas' position on slavery. Though Douglas won the Senate seat the following November, Lincoln's reputation as a spokesman against the extension of slavery helped catapult him to fame and into the White House in 1860. —Owen W. Muelder is director of the Galesburg Colony Underground Railroad Freedom Station at Knox College. Illlinois Heritage 11 |

|

|