|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Cheryl Lyon-Jenness In the middle decades of the nineteenth-century, an astonishing change took place in rural and urban landscapes across America. Flower gardens, orchards, and even shade trees and lawns, once the provenance of the wealthy or those with particular horticultural interest, proliferated as citizens of all economic ranks and circumstances began ornamenting their dooryards with plants. The agricultural press was filled with observations about the nation's new-found horticultural enthusiasm. In 1858, for example, a midwestern pundit noted, "There has sprung up amongst the [citizens] a desire for horticultural embellishment and there are many private residences now adorned with conservatories and fruit and flower gardens, where there had been nothing of the kind." Several years later a Chicago observer pointed out that seed sales were booming, because even "the poor man must have his packages of Balsams, Asters and Scarlet Runners, and the man of moderate means sends his one or two dollars to the seedsmen."

Although the nursery trade was newly established in mid-nineteenth-century Illinois, the state had its share of vocal horticultural proponents who joined colleagues from across the nation in promoting horticulture and its benefits: O. B. Galusha, a nurseryman and agricultural leader from Kendall County, Matthias L. Dunlap, an important figure in the state agricultural association and farmer from Champaign County, and Jonathan Baldwin Turner, college professor turned agricultural and educational activist, from Jacksonville, Illinois. Among this illustrious group, Dr. John A. Kennicott was one of the first and most influential leaders to take a stand for horticulture, and his life and efforts offer us a model for understanding nineteenth-

2

Affectionately known as the "Old Doctor," John Kennicott had several detours on the road to Illinois and horticultural promotion. He was born about 1800 in Montgomery County, New York, the son of Jonathan and Jane Kennicott. Jonathan Kennicott was an inventive farmer who sparked interest in new agricultural practices and labor-saving devices, while Jane Kennicott, an avid gardener, encouraged young John's interest in plant culture. During his childhood, the family, eventually including fourteen children, moved several times, finally settling in Cattaraugus County, where in the wilds of western New York, John had even greater opportunity to pursue his interests in natural history, botany, and horticulture. Largely self-educated as a child, John Kennicott dreamed of being a physician, and in 1823, he left the family farm to seek opportunity in Buffalo, New York. In his new home, Kennicott taught school, worked in a drugstore, and studied medicine, taking course work at a medical college in Fairfield, New York, when time and means allowed. His training completed, Dr. Kennicott practiced medicine briefly in Canada, traveled through the Midwest, and with his new wife Mary Ransom, eventually settled in New Orleans where he served as a physician, as the principal of a large primary school, and as director of the New Orleans Boys' Orphan Asylum. Foreshadowing later efforts to provide information and promote education, Kennicott, along with his brother James, also established the Louisiana Recorder and Literary Gazette, described by one commentator as the "first literary, scientific, and religious paper ever printed in New Orleans." While John Kennicott and his young family were putting down roots in the South, several other Kennicott family members purchased acreage on the northern Illinois frontier. In 1836 Kennicott, his wife, and their two sons, Charles and Robert, joined them, settling in a prairie grove northwest of Chicago. Their new home, dubbed The Grove, bordered the Milwaukee Road and is today part of The Grove National Historic Landmark located near the community of Glenview. In describing those early years, John Kennicott noted that when they arrived, the region was sparsely populated and the "naked prairies" devoid of "even so much as a currant bush." Once settled at The Grove, Kennicott established a medical practice to serve the rural families scattered across the region. His medical skills and his kindness in ministering to the needs of local people soon brought him acclaim, but his heart was in horticulture. In 1842, with his ten-year-old son Charles as partner, Kennicott opened his beloved Grove Nursery and Gardens, and until his death in 1863, worked to expand and improve his inventory of plants suitable for midwestern growing conditions. As the family grew, all of the Kennicott children played at least some role in the nursery business. Charles continued in partnership with his father until establishing his own nursery near Sandoval, Illinois, in the 1850s. The Kennicott daughters, Cora and Alice, also assisted their father, and Cora was especially active during the Civil War when military service called other workers away from horticultural tasks at The Grove. Amasa, the third of the Kennicott boys, returned from military service to manage the nursery after John Kennicott's death in 1863. His brothers, Robert, Ira, and Flint, eventually pursued  3

different careers, but pitched in with nursery chores when demand for trees and flowers called for extra hands. Through the family's efforts, the Grove Nursery and Gardens grew to over forty acres and offered customers a reliable source of trees, shrubs, herbaceous perennials, and over 150 varieties of roses. Kennicott's reputation as a knowledgeable nurseryman spread quickly, but soon he was also known as a passionate promoter of progressive agricultural and horticultural practices Citizens learned of Kennicott's views in several ways. Even by nineteenth-century standards, Kennicott carried on a voluminous correspondence, sharing his knowledge and enthusiasm for plants with like-minded advocates nationwide and with thousands of midwesterners who wrote for trees and flowers or to seek horticultural advice. Expressing his views to an even wider audience, Kennicott routinely penned essays for agricultural papers like Moore's Rural New Yorker and prominent horticultural journals like the Gardener's Monthly or the Horticulturist, Illinois residents were most likely to come across his work in the Chicago-based Prairie Farmer. Kennicott began contributing articles to the Farmer in the 1840s, served as horticultural editor in the 1850s, and continued to write for the paper until his death. In addition, Kennicott edited the first volumes of the Transactions of the Illinois State Agricultural Society and frequently composed essays for later editions of agricultural and horticultural society reports. Interested citizens sometimes invited Kennicott to speak before local and state organizations, and as a result, audiences throughout the Midwest came to know his dedication to horticultural advancement firsthand.

The practical benefits of horticulture had merit, but Kennicott, and others who shared his perspective, were not afraid to claim that plant culture had even greater significance for Illinois and the nation. "The practice of horticulture," Kennicott told Prairie Farmer readers, "has sparked the civilization, taste, and prosperity of nations." He repeated this theme many times, explaining that, in his view, gardens were "public preachers" and could inculcate important social values like hard work, good taste, and refinement among those who enjoyed their benefits. Homes carefully adorned with trees and flowers, Kennicott insisted, helped to "form the moral and physical character of the inmates." In addition, ornamental plants offered residents a close and very pleasurable connection to the natural world. This enjoyment of "beautiful trees and flowers," Kennicott argued, had "refining tendencies," and could enhance a spiritual link to God. This perceived power of 4 horticulture to shape behaviors and promote shared values made it a particularly important tool in the hands of proponents contemplating rural reform. Those who loved trees and flowers, advocates reasoned, would also come to value education or employ scientific agricultural practices, both critical components of a progressive rural society.

As he championed horticulture regionally, Kennicott recognized that sustained interest and progress required resources far beyond the reach of local communities, and he eventually turned to government as a way to further support for the cause. At the federal level, an underfunded division of the Patent Office had represented the nation's agricultural and horticultural interests for decades. Noting the inadequacy of this arrangement, Kennicott bluntly charged that the federal government had "done nothing for agriculture." With others who shared his vision, Kennicott insisted that a federal Department of Agriculture was both long overdue and necessary to support continued progress in agricultural and horticultural practice. Because of his knowledge and even-handed approach, many thought Kennicott a likely choice to head the proposed department, and the Illinois legislature as well as respected agricultural leaders endorsed his nomination. In addition, Kennicott thought the federal government had a role to play in democratizing educational opportunity. Since the early 1850s, a movement for "industrial education" led by reformer Jonathan Baldwin Turner had been bubbling in Illinois, and as Turner pointed out, Kennicott gave his "heart and enthusiasm" to what came to be known as the "Illinois idea." The concept called for a revolutionary new system of state universities supported by an endowment of federal land or "land grants." These institutions, their supporters hoped, would provide a "liberal and practical education of our industrial classes and their teachers," and would, in turn, advance horticultural and agricultural progress. What did John Kennicott and his fellow advocates accomplish in this "golden age" of horticultural activism? At the time of his death in June 1863, Kennicott was a venerated and widely known horticultural proponent, and in some measure, the results of his advocacy 5

were readily apparent. When he established the Grove Nursery in 1842, for example, a handful of Illinois nurserymen catered to the horticultural wants of Illinois residents. Only a few decades later, dozens of bustling enterprises struggled to keep up with increasing demand for trees and flowers. In addition, the agricultural and horticultural press and associations, so fervently promoted by advocates, continued to draw new readership and new members as the century wore on. Even the larger battle to win national recognition for the horticultural cause had a favorable outcome. Although John Kennicott was not at the helm, the United States Department of Agriculture, established in 1862, gave horticultural and agricultural interests a voice and a home in federal government. And to the delight of supporters like Turner and Kennicott, the Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862 allocated federal lands as subsidy for state universities catering to the practical needs of farmers and mechanics. For most Illinois residents, however, the benefits of horticultural advocacy were much closer to home. "We can read the record of Kennicott's life on our Illinois prairies," friend and fellow nurseryman Charles D. Bragdon declared as he eulogized Kennicott in 1863, "in the planting of groves and belts of trees, orchards, hedges, shrubs and flowers, by the adornment of bowers, the consecration of home to the highest and purest enjoyments." Horticultural interest had indeed transformed the Illinois landscape, but whether, as proponents hoped, orchards and gardens had also changed rural society is much more difficult to assess. Kennicott firmly believed that plant culture could bring beauty, comfort, and good health into the lives of the "plain hardworking" Illinois residents and at the same time would shape values and improve behaviors. Horticultural interest, in other words, could help reformers build a progressive rural society ready to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing national culture. While trees and flowers may have had a "refining influence" on some, the call for rural reform did not end with the mid-nineteenth-century horticultural boom. Long after Kennicott's death, efforts ranging from the Grange movement of the late nineteenth century to the County Life movement of the early twentieth century, continued to promote changes in rural society, suggesting that this portion of John Kennicott's horticultural dream remained elusive.  James J. Schebler Overview

In the one hundred years after the American Revolution, as settlers pushed westward from the original states, great changes developed in all aspects of life, including political, economic, cultural, social, and scientific. Many of those changes can be seen in the practice of farming. Although there had been some agricultural and horticultural experimentation in the English Colonies and in the earliest American states, the new lands to the west—the Northwest Territory, Louisiana Purchase, etc.—presented great opportunities and challenges for agriculture. The government's bequest of land to veterans and the availability of inexpensive land in the West led to an unprecedented migration of people. They settled on prime agricultural land where they were ready to accept new farming methods, new machinery, and new plant varieties. The material in this section will examine some of the agricultural and horticultural aspects of the westward movement, primarily through the life of John Kennicott and his time in Illinois (1830s to the 1860s). Students will be asked to: (1) analyze John Kennicott's contributions to agriculture and horticulture; (2) examine the changes in agriculture prompted by Kennicott and others; and (3) make connections to events today that were set in motion during this time. We will also examine the preservation of state and national heritage through the creation of significant environmental and historic preserves, including the preservation of land, buildings, and records. 6 Connection with the Curriculum The narrative and activities may be appropriate for the following Illinois Learning Standards: (1) Government/ Political Science-14.D.5, 14.F.5; (2) Economic Systems-15.C.4b; (3) History-16.A.4a, 16.E.3b; (4) Geography-17.C. 3a; and (5) Social Systems-18.B.4 Teaching Level Grades 6-12 Grades 6, 7, and 8 may require more background information and clarification of the materials included here. Grades 11 and 12 can go beyond the materials provided and conduct additional research in textbooks, periodicals, and library materials, and on the Internet. Some suggestions are offered in the section Teaching the Lesson. Materials for Each Student A copy of the narrative portion of this article and a copy of the activities that will be used should be furnished to each student. United States history textbooks and/or Illinois history textbooks would be helpful. Easy access to a library/materials center and to the Internet would be very useful. Objectives for Each Student • Examine and evaluate the contributions of John Kennicott and others to the agricultural/horticultural movements of the mid-1800s. SUGGESTIONS FOR TEACHING THE LESSON Opening the Lesson Sometimes it is a good idea to have the students read and study the worksheet/activity before reading the article. This helps them to identify terms and other information that will help them complete the assignment. A class discussion of the assignment can clear up problems that students might have with vocabulary, sources of information, and assignment expectations. The lesson can be opened by initiating a discussion of how students view agriculture today. While responses will vary depending on the community and student experiences, the following points may be considered: (1) What is the importance of agriculture in this community, in Illinois, in the United States, in the world? (2) How has the production of food changed in the last 200 years? (3) What, besides agriculture, has been changed by our modern food production system? (4) Who are some of the people that you have heard of who changed agricultural practices in the United States/Illinois? (Likely responses may be Thomas Jefferson, Cyrus McCormick, and John Deere).  7

At this point you might assign the reading of the narrative on John Kennicott and assign the completion of Activity 1 —Vocabulary and Comprehension. This could be assigned for homework as an individual, or as a small group activity. Discussing this activity should provide a good overview of the topic. Developing the Lesson These activities are designed to be independent of each other and also can be used in any order. Some adaptation will permit the activities to be used at middle school or high school level. In some cases, parts of an activity may be used or the activities combined. Activity 1 — Vocabulary and Comprehension. This is designed to acquaint the student with the vocabulary and information contained in the narrative. Any standard dictionary can be used to look up words on the list. Remind students to find definitions that would be related to the theme of the article. After finding appropriate definitions, the students should write sentences related to the topic using the vocabulary words. Have students complete this activity by answering the questions in Part III, or use these questions for a class discussion. This exercise can be completed individually, in small groups, or assigned for homework. Activity 2—Fact, Explanation, Analysis. In this activity two questions are presented on each topic from the narrative. The first question in each set can be answered by finding a factual bit of information. The second question in each set asks the student to explain, analyze, or speculate on this information. Once again, this can be used as an individual activity, small group activity, or the basis for a class discussion.

Activity 4—An Alternative Horticultural Acquisition. This account of an 1840s incident gives an interesting view of how new crops might be acquired by an Illinois farmer before new horticultural varieties were available from nurseries or when economic conditions limited the farmer's choices. Follow-up discussions might help students understand financial limitations faced by some early farmers. The 1840s account also illustrates the limited availability of plants to farmers and their inattention to scientific agricultural principles. A discussion contrasting 1840s agricultural practices with those evident in today's agricultural ads on television could be developed. Activity 5—Mapping John Kennicott's Migration Westward. Using a map of the eastern half of the United States, locate John Kennicott's route from his birthplace in Montgomery County, New York, to his final home, The Grove, near Glenview, Illinois, on what became known as the Milwaukee Plank Road. The materials asked for below the map can be used to discuss and speculate about his westward movement and compare it to other routes into Illinois used by new settlers. 8 Activity 6—Historic Preservation. This activity should give the students a practical look at the process and criteria required to place a property on a list of historic places. John Kennicott's Grove is on the National Register of Historic Places. Individually or in small groups, your students can select a local property and develop information on that property using established guidelines for historical registration. The property selected could be a local public property or a property owned by a cooperative local resident. Help for this project could be secured from a local historical or preservation society. Concluding the Lesson Class discussions of the following topics could bring closure to this lesson: 1. Compare the contributions of John Kennicott with other developments in agriculture in the 1800s: that is, John Deere's plow, Cyrus McCormick's reaper, and Joseph Glidden's barbed wire as well as those agricultural advocates mentioned in the narrative. Discuss how all agricultural/horticultural innovations contributed to the development of the Midwest as one of the prime food-producing areas of the world. 2. Discuss the role of support industries in the development of midwestern agriculture since 1800 (transportation—water, railroad, highway, airplane; chemical—fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides; manufacturing—tractors, farm implements.) 3. Imagine that you are a farmer in Illinois in 1850. What selling points could Kennicott's nurseries emphasize to make you want to buy their new plant varieties (such as increased yield, less labor to grow plants, and varieties more tolerant of drought). 4. Why should anyone in urban areas be concerned about the work of men like John Kennicott and agricultural issues in general? Consider our food supply and jobs in construction, transportation, retailing, and education. 5. What was the reason that John Kennicott and others supported the formation of agricultural/horticultural societies, agricultural publications, county and state fairs, and the establishment of state and federal departments of agriculture? 6. What role does the United States Department of Agriculture play in agriculture/horticulture today. (You could consult a government text, United States Department of Agriculture website, almanac, or encyclopedia for information on this topic.) 7. What is the role that designated historic sites such as John Kennicott's The Grove play in our understanding and appreciation of history and historic events?

Some of the activities outlined in this section will require students to supplement the material here. Below are some additional resources. Students could use the Internet to explore and to prepare additional reports on The Grove and John Kennicott, the history of the community of Glenview, historical developments in the area of agriculture/horticulture, and so on. An activity that could be interesting and profitable for the students would be either a fieldtrip to a local nursery, agricultural extension office, Farm Bureau office, or the agriculture department of a university. This could provide interesting insights into past agricultural events as well as information on current agricultural practices. If a field trip is not possible, you might consider inviting a guest from one of these agencies to make a presentation in your classroom. Be sure to establish the topic(s) that you want discussed in the class. Some pertinent Internet sites that might be worth visiting by you and your students include: National Park Service/National Register of Historic Place National Trust for Historic Preservation Illinois Historic Preservation Agency 9 Glenview, Illinois History Kennicott Brothers Company United States Department of Agriculture Information on The Grove (History and present use) Assessing the Lesson Teachers can assess the students' progress on this lesson by constructing a traditional quiz/test on the topics covered or by including material from this lesson in unit, quarter, or semester tests. Grading rubrics could be used to assess projects as they are completed. This would work well for additional assignments, projects, and reports. Some of the topics in this lesson might lend themselves to inclusion in future history fair projects.

10

agriculture Part II. Write a sentence for each of the words defined above. Be sure that the sentence is relevant to the content of this article. Try to weave the sentences into a paragraph form. You may use the words in any order. Part III. Answer the following questions briefly. 1. What is the main theme of this article? 11  Below you will find sets of questions. In each set there are two questions. The first question is a question of fact based on items contained in the narrative. The second question in each set asks you to analyze or speculate about something based on the answer to the first question.

1.b. What connection can you establish between his early occupations and his final occupational choice? 2.a. Name and list the accomplishment of at least three other people active in the agricultural movements during this time period. 2.b. How did these people and their activities complement or help advance the work of nurserymen like John Kennicott? 3.a. List three arguments used by John Kennicott to urge midwesterners to plant trees, shrubs, and flowers on their property. 3.b. Would these arguments still be valid today? Why?/Why not? 4.a. List two actions advocated by Kenicott, Turner and others that would take place on the federal level. 4.b. What would be the benefit to people in the 1800s from these projects by the federal government? What would be the benefit to us today because of these two programs? 12

C. 1800 Kennicott was born in New York state, one of fourteen children 1801 (1)________was inaugurated President 1823 Left home and moved to Buffalo, taught school, and studied medicine part time 1829 Married Mary Shutts (4)_______________ 1829 Andrew Jackson inaugurated President 1836 After working in the South as an editor and a physician, he moved to Illinois 1837 City of Chicago is incorporated 1842 With his son, Charles, he established Grove Nursery and Gardens 1840s Began contributing articles to a periodical called Farmer 1845 (7)__________________annexed to United States 1850s Served as horticultural editor for Farmer magazine 1850s Kennicott pushed for "industrial education" along with Jonathan Baldwin (9)____ 1853 Promoted formation of Illinois State Agricultural Society 1853 Actively supported formation of the Illinois State Horticultural Society 1855 First railroad bridge across the (10)_______River at Rock Island, Illinois 1863 John Kennicott died at his home, The Grove Essay/Discussion Questions 1. Choose three events from the Illinois/United States chronology and tell how agriculture and/or John Kennicott's enterprises might be affected by these events 2. Imagine that you are a friend of John Kennicott's. Write John a letter taking a stand on one of the events listed above and discuss why you are taking this stand. Keep in mind the time period involved with this event. 3. Write a letter to President Lincoln recommending John Kennicott for the newly created position of Secretary of Agriculture. Be sure to emphasize why he would be qualified for this position. Remember what time this is in our history. 13

Read Abraham Miller's account of this encounter with the person that he calls "the old Economiser," then answers the questions that follow. This article is presented as it was written and transcribed; spelling, punctuation, and grammar have not been modernized. Early Orchard &c The first class of settlers went slow towards getting out Orchards of any size or kind. The first fruit trees to my knowledge in our locality were derived from planting the seed and as the trees grew generally remained seedlings, bearing such fruit as chanced to be. Some got seed one way and some another, but most generally from a few apples or peaches which chanced to fall in their way; either brought up the river on boats or carried through by some man peddling fruit on a small scale. My memory treacheeous as it is yet very distinctly serves me of how one old economiser got his first peach seeds. He was about a second class settler. Upon a muster day or some other public parade a peddler came into Millersburgh in its earliest commencement selling out small half green peaches at a bit a dozen. The boys were eagerly demolishing this rare fruit and throwing the seeds down where ever it happened: while our old Economizer was as busily engaged picking up every seed he could find and dropping them into his blue janes coat & butter nut breeches pockets. Fearing that he might not get enough, he came to me and proposed to borrow a bit to invest in peaches. He was quite a forehanded farmer for those days. I handed him a bit, he purchased a dozen, tied them up in his mock cotton bandana handkerchief. Questions on this document: 1. Use a dictionary to find out the value of "a bit." 2. What does "old Economizer" intend to do with the peach seeds that he gathered from the ground and the peaches he bought? 3. What do you think is the attitude of the writer of this piece toward "the old Economizer?" 4. Why do you imagine that "the old Economizer" would not just order peach trees from John Kennicott's nursery near Chicago? 5. List two advantages and two disadvantages of acquiring peach trees the way "the old Economizer" was doing it, compared to ordering them from nursery stock. 6. Imagine that you are a sales representative for Kennicott's nursery in the 1840s. Write an ad for a farmer's magazine trying to get farmers in Illinois to buy peach trees from you. 7. Re-write the story above using modern language, and correct grammar, spelling, and punctuation. 14

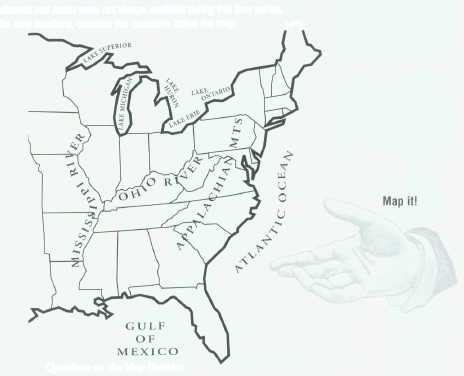

Using the map of the eastern United States below, trace the travels of John Kennicott from his birthplace in Montgomery County, New York, (near Saratoga), to his eventual arrival at The Grove, near Glenview, Illinois. You will need an atlas or another source of maps to complete this activity. Include in his route: Buffalo, New York; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Glenview, Illinois. To get to New Orleans, Kennicott traveled by way of Canada and traveled through the Midwest before arriving in New Orleans. Label these locations on the map and roughly trace the route outlined above. Remember that railroads and roads were not always available during this time period. When you finish the map locations, consider the questions below the map.  Questions on the Map Exercise 1. List two reasons why a physician such as John Kennicott would be attracted to move west to new settlements. 2. Is it likely for an individual today to have such a variety of occupations as those that are listed for John Kennicott in his migration from New York to Illinois by way of Louisiana? Why not? 3. On the map, draw at least two other routes from New York to Illinois using more direct paths than those followed by John Kennicott. Would paths using water be preferable to land routes? Explain. 4. Do you know of anybody in your family who came from the East to settle in the Midwest? When did they come? How did they travel? What route did they take? Share these stories with your classmates. 15  John Kennicott's property in Glenview, Illinois, is a National Historic Landmark. The 124-acre tract is managed by the Glenview Park District. Heritage is preserved through historic properties, historic documents, photographs, and historic artifacts. Through museums, historic buildings, libraries, and local and state historical groups, Americans have developed ideas of us as a people—who we were, who we are today, and where we are going tomorrow. Projects such as The Grove of John Kennicott help us do this. In this project you have the opportunity to identify properties in your own area that might have historical significance. With the help of local historic groups and your teacher, the following exercise might help uncover some of these properties. Brainstorm with your teacher and the class about where some of these properties might be located, and start your exploration of these properties by finding the answer to some of the questions below.

2. What kind of property is it? (House, barn, store, factory, etc.) 3. Who owns the property? Can you interview the current owners? 4. When was it originally built? When was it enlarged? 5. Why is it significant? (Historic person lived there, historic event took place there, etc.) 6. What is the condition of the property? 7. What is located around the property? (Other buildings, vacant land, etc.) 8. Can you get current photos of the property? Can you find old photos or sketches of the property? 9. Can you find a current detailed map of the area? Can you locate older maps of the area? 10. Can you talk to anyone (neighbors, former workers, public officials, etc.) who would have additional information about the property? 11. Has anything been done before to research this historic property? As you progress on your investigation, you can find additional information and direction at the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency website <www.state.il.us/hpa> and at the National Register of Historic Places website <www.cr.nps.gov/nr>. Be sure that your group keeps accurate records of your findings and respects private property. Happy researching! 16 |

|

|