|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

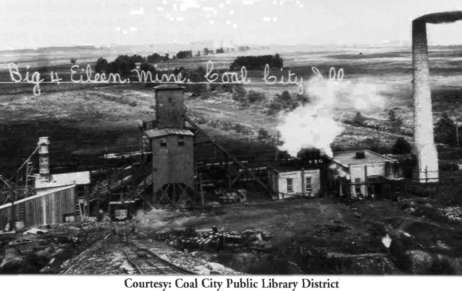

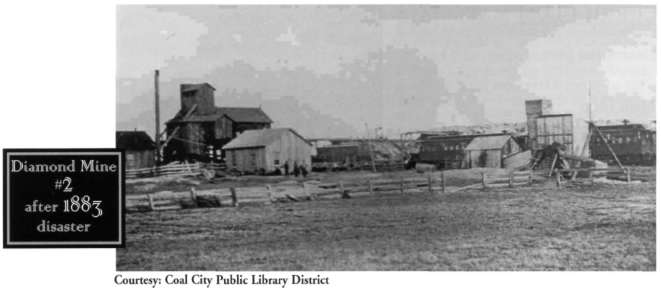

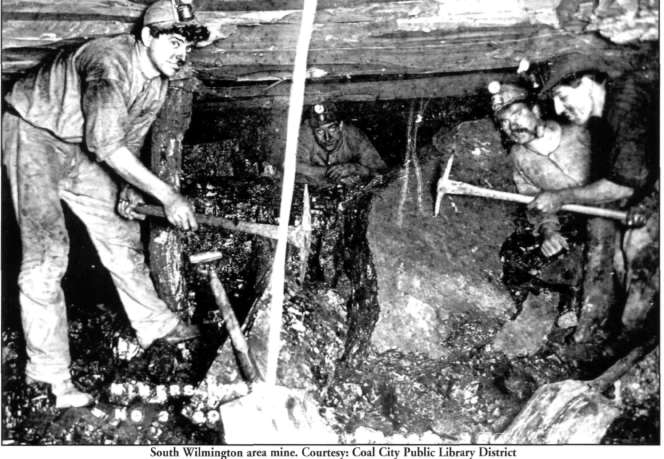

The development of huge tracts of valuable coal land and their exploitation by corporate concerns in and near Braidwood in southwest coal center in the state by 1870. The largest of several coal companies at Braidwood eventually became the Chicago, Wilmington, and Vermillion (later Franklin) Coal Company, which also operated mines at Streator (LaSalle County), Seatonville (Bureau County), and South Wilmington (Grundy County). The other corporations that entered the field followed a similar pattern of land purchase, erection of mine apparatus, sinking of shaft(s), recruitment of a labor force, platting of a town site, and erection of a company office and homes for miners. Some of the companies donated land for parks and churches. News of the opening of new mines brought an influx of miners from Europe and other parts of the United States. From its beginning, the mine workforce in the northern Illinois coalfields was composed primarily of immigrants and their children. Miners from the British Isles—Scots, Irish, English, and Welsh—predominated from the 1860s into the 1880s. Braidwood, for example, was named for a Scottish immigrant miner, James Braidwood, who helped sink the first shafts there. Likewise, Cherry, a coal town developed in Bureau County in the early 1900s, was named for mine superintendent James Cherry, an English immigrant. Miners from continental Europe began arriving in the 1870s, and they came in much larger numbers in the next three decades. Although Italians were the largest of the immigrant mining groups, sizeable contingents of Bohemians, Lithuanians, Poles, Russians, Germans, Belgians, and other groups also were present. The immigrants brought with them recipes, sports, organizations, and ancient hatreds. For example, a riot occurred on election day in Braidwood in 1876, when Irish Catholics and Scotch Protestants battled for township offices. In sports, soccer teams from Braidwood and Carbon Hill competed successfully against teams from other parts of the United States and from England. Ethnic organizations proliferated, and several opened cemeteries and built halls for social and cultural events. Another group of miners were African-Americans, who first appeared in large numbers in the region when they were brought in by the coal companies during or soon after strikes at Braidwood in 1877 and Spring Valley in 1894. In 1880 Braidwood had 386 black residents, the largest contingent of black miners in the area, although blacks were present in smaller numbers in many of the coal towns. Racial relations were often difficult at first; white mobs chased blacks from Braidwood in 1877 and Spring Valley in 1895, and some blacks moved on to break strikes elsewhere. 2 Others, however, remained, and a few were elected to public office or to positions of leadership in local unions. Regardless of their background or nation of origin, miners faced similar conditions above and below ground, and this was a source of unity for the underground toilers. Lives of the men who hacked away at the coal seams in the four-foot-high tunnels in the bowels of the earth faced danger from roof cave-ins, stale air, explosions, fires, floods, equipment failure, and human error. Although mine accidents usually injured or killed miners individually, occasional but deadly mine disasters destroyed many lives at once. A flood of surface water into a mine at Diamond on February 16, 1883, killed more than seventy miners. In November, 1909, 259 miners perished in a mine fire at Cherry in Bureau County. These tragedies led to the passage of mine safety and workmen's compensation laws.

Miners responded to their difficulties by forming organizations. Many miners belonged to ethnic and/or fraternal organizations, such as the Knights of Pythias, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, or the White Tie Lodge. For a small membership fee, those organizations provided sickness and death benefits for miners and their families. They raised money and provided a social outlet for miners by sponsoring dances, picnics, raffles.and suppers. Miners also organized politically. Several northern Illinois miners were elected to the General Assembly, where they sponsored laws favoring mine safety, weekly pay, abolition of company stores, and gross weight (which required the companies to pay for all the coal that the miners loaded). Many minor parties had substantial support in the coal towns, including Greenback-Laborites, Populists, Socialists, and Prohibitionists, and local elections were often hotly contested. This was especially true when local mine superintendents ran for local office or when strikes loomed. In 1877, for example, with a strike pending, slates led by mine union leader Daniel McLaughlin and his supporters swept city and township elections in Braidwood. Miners opposed to Spring Valley Coal Company superintendent Sam Dalzell and his supporters fought a number of bitter elections for at least a dozen years after Dalzell's arrival in 1889. In nearby Ladd, a disputed village election between the local mine superintendent and a popular saloonkeeper ended up in the state supreme court. Control of village, township, or school government was crucial during strikes, as sympathetic officeholders hired striking miners to paint or repair buildings, dig ditches or work on city streets, or to serve as deputies or election judges. Also, class, ethnic, and religious differences split the citizenry of the coal towns, to the detriment of the men who were trying to unite the miners. As early as 1868, northern Illinois miners struck against wage cuts as members of the American Miners' Association. John James, an experienced miner-unionist from Scotland, was blacklisted for his activities during this  3

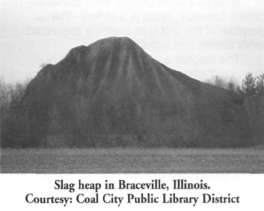

As the railroads crisscrossed the nation, the coal industry became more competitive in the late 1800s, and coal companies reduced both the price of coal and the price paid to miners. Miners in northern Illinois struck in 1868, 1874, 1877, 1889, 1894, and 1897. The use of strikebreakers or threats against company property often brought Pinkerton detectives, county police, or the National Guard into the mining villages. Miners' homes were searched for weapons, and two men were shot and killed by United States troops guarding the railroad at Spring Valley during the 1894 strike. Miners usually sat out all summer and part of the fall before giving in and returning to work at lower pay. Other miners left the area to look for work elsewhere. The termination of a strike commonly involved blacklisting of prominent strikers, signing of yellowdog (promising not to join a union or go on strike) annual contracts, and an ever lower standard of living. The success of the miners in the 1897 strike owed much to the improving economy. Coal corporations, eager to take part in the upturn, accepted a new interstate agreement that provided for the eight-hour day, payment for all coal raised to the top, and a pay raise. This victory helped solidify the position of the young UMWA and gave a boost to Mitchell's career. Although new shafts were sunk and several new towns such as Dalzell, South Wilmington, Torino, Cherry, and Cardiff were created around the turn of the century, the glory days of mining in northern Illinois ended during the 1920s, when many of the large corporations left to open new mines with thicker coal seams in other areas of the state. Local entrepreneurs now operated the mines at a much-reduced level, and the population of the coal towns plummeted as many miners sought jobs elsewhere. During that same decade, strip mining began in northern Illinois. The last shaft mine in northern Illinois closed in 1954, and twenty years later, the last strip mine ceased operations. The coal industry left a heritage of ethnic diversity and pro-union attitude still present in the old coal towns. Much of the strip-mined land has been transformed into recreation areas for swimming, boating, fishing and camping, and new residents often inquire about the huge solitary slag heaps that dot the nearby agricultural prairie, unaware of the rich past of an industry and its workers who brought them into existence more than a century ago.  4 CURRICULUM MATERIALSby Evelyn R. Holt OttenOverviewMain Ideas Labor history is rich and varied, as demonstrated by the narrative on the coal fields of northern Illinois. As students examine the narrative and conduct further research, they will have a better understanding of labor history and the role(s) of labor unions.

Teaching Level Materials for Each Student • A copy of the narrative portion of this article • A copy of the activity handouts 1-3 • A United States history textbook Objectives for Each Student • Identify multiple perspectives as related to the topic of organized labor • Research a town meeting and be a participatory citizen in its enactment • Examine costs and benefits of union organizing • Identify examples of anti-union actions in Illinois history • Cite examples of union organizing in United States history

5  tool of labor. Although these are examples of strikes and labor activity in various places of the United States, students will understand there are common factors shared by workers in these events. The narrative provides evidence for the Spring Valley Coal Company strike in 1894. Further research is necessary to complete the remainder of the chart. Concluding the Lesson For a concluding lesson, the students can review the previous activities, noting the multiple perspectives relating to the issues of labor unions.

Assessing the Lesson Assess the unit based on how thoroughly and logically students complete their solutions to the posed questions. An evaluation rubric is included as part of Activity One. Since the topic of unionism is open-ended, students' reactions will vary. There is no single correct conclusion.  6 Activity 1You are a citizen of Braidwood, Illinois. A proposed town meeting will address the topic of unionism. A town meeting provides an opportunity for all points of view to be expressed. Research and discuss the pros and cons from the perspectives of:

Other roles may be added as long as they are relevant to the discussion. Role-play for extension of learning. Write letters to the editor of the local paper addressing the issues. Use at least two issues in the arguments you develop. Evaluation based on Relevance to topic of argument (20), Research (10), Presentation (15) and Bibliography (5) (Total 50).  7 Activity 2"A picture is worth a thousand words." Examine photos of mine workers and mine towns from state and national archive collections (www.nationalarchives.gov). Focus on faces of the workers for comparative ages and conditions. What types of hardships did these workers face? Look especially at child laborers. What types of work did they do? How much were children compensated compared to an adult worker? What kind of life forecast would there probably be for the child worker? Listen to the song "Sixteen Tons" by Tennessee Ernie Ford. Discuss how that song relates to the mine situation and the lives of miners in northern Illinois coal fields. Compute a miner's pay based on information in the song and narrative

8 Activity 3STRIKE! One of the most dreaded words in labor's vocabulary, the strike was usually the final weapon used from labor's arsenal. In this activity, students will examine some examples of strikes and labor disputes to determine the similarities and differences among events.  Students may research history texts, encyclopedias, web sites, etc. How were these events similar? How were they different? What can you conclude from these events? Research other strikes to compare to the ones listed here. 9 |

|

|