|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

www.ILparks.org November/December 2006 20

Often nature is the inspiration for cutting-edge technology. So it is with emerging systems for managing stormwater, which in today's heavily built environment can flood ballfields and basements, pollute streams and cost taxpayers millions. Before all the streets, parking lots, office buildings, shopping malls and other hallmarks of modern development transformed the Illinois landscape, storms that produced more rainfall than the ground could absorb produced ephemeral, or temporary, streams. These streams naturally formed in low areas to accommodate the stormwater. Eventually, the water would either soak into the soil or drain into a pond or waterway. And then the stream would dry up. Even with so much of the environment built up today, ephemeral streams still form. You can see them in open fields, farm fields, even on construction sites. If the latest trends in stormwater management are any indication, you will see more of them. The difference is that they will be designed by people. Engineered ephemeral streams are called bioswales. They are part of a new, cost-effective environmentally friendly and landscape-beautifying approach to managing stormwater -- an approach that your agency can take advantage of to help protect your facilities and communities from flooding and from poor water quality. www.ILparks.org November/December 2006 21

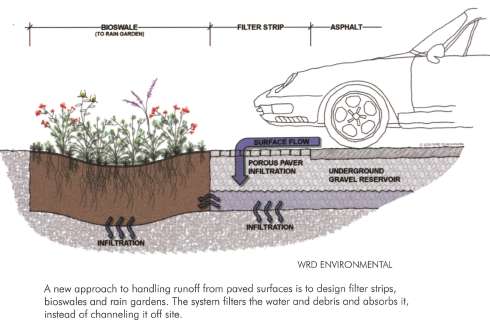

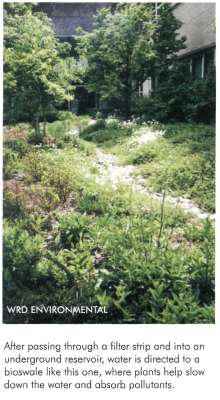

Paving and Stormwater Runoff Pavement is notorious for contributing to flooding and pollution. During heavy storms, rainfall runs off, picking up pollutants like motor oil, antifreeze, litter and grime. Then the water speeds unimpeded via municipal sewer systems which carry rainwater runoff and sewage together - into local waterways. If those waterways cannot accommodate the sudden influx, they flood. They also become the depository for all the pollutants the stormwater picks up along the way, as well as the acccompanying sewage. Because of the volume and speed of rainwater running off of them, parking lots, sidewalks, skate parks, tennis courts and other paved areas reduce the landscape's ability to naturally absorb rainwater, contributing to flooded Streets and basements. Slowing down stormwater is the key to managing it in a more effective and environmentally friendly way. Permeable Paving Using permeable concrete pavers that allow water to drain into the soil is an effective way to reduce stormwater runoff (see Engneering Miracles with Innovative Stormwater Design, May/June 2005). Rainfall percolates through spaces between the pavers into an engineered reservoir, or sub base. With the right conditions, parking lots and other paved areas consisting of permeable pavers can slow down rainfall sufficiently to replenish groundwater, as water seeps from the reservoir into the surrounding area. Draining through crushed stone between the permeable pavers, the water begins to be filtered of pollutants it has picked up from the pavement. Another benefit is that, depending on the size of the porous paving system, the need for costly sewers, catch basins and other infrastructure can be reduced or eliminated. Parking lots and other paved areas made of permeable concrete pavers are not a panacea, however. If the reservoir beneath a paved area is situated above clay soil, which is common throughout Illinois, stormwater can become trapped in the reservoir. An impermeable clay soil may prevent the water from draining effectively into subsurface soils, unless costly infiltration trenches or pipes are added. With nowhere to go, the water will move laterally --similar to if it were on the paved surface -- and in winter be subjected to freeze-thaw cycles and potentially buckle the pavement. In this case, the system may do more harm than good. Compacted soils, which are also common in developed areas, present similar problems. The other drawback to using permeable pavers over an entire paved site is the upfront cost. While they can save money over the life of a project by reducing or eliminating infrastructure, permeable pavers and their installation cost considerably more at the outset than traditional concrete and asphalt paving. A combination of traditional paving and permeable pavers, coupled with bioswales and naturalistic "rain gardens," is a new cost-effective, environmentally friendly approach to stormwater management. With this new system, a parking lot, for instance, consists primarily of asphalt or concrete paving that extends up to the parking bumpers at the peripheries. Roughly five to ten feet beyond the parking bumpers is a "filter strip" made of permeable pavers. The filter strip serves to slow down the stormwater running off of the pavement, giving it time to percolate down between the pavers to a sub-base reservoir. As the water drains through the permeable pavers, pollutants begin to filter out. From the underground reservoir, the water seeps into a nearby bioswale. Linear depressions lined with plants that tolerate wet soil conditions, bioswales continue the functions of the www.ILparks.org November/December 2006 22

filter strip and channel the water away from the area, taking the place of pipes. The plants help to further slow down the stormwater and absorb it, reducing the amount of stormwater that flows out of the bioswale. The plants also continue to filter out pollutants and sediment from the water, picking up where the filter strip left off. Stormwater that is not absorbed by the bioswale continues on to a rain garden. Like a bioswale, a rain garden is filled with plants that can handle wet conditions, most of them being native plants. Unlike a bioswale that is intended to direct water elsewhere, a rain garden is a destination of sorts. Water that collects there pauses until it eventually drains into the soil or evaporates. A properly designed and constructed rain garden will usually drain within an hour or two, and certainly within 24 hours. This natural approach to stormwater management is not only useful for paved areas, but it can also apply to other district facilities. Baseball fields, soccer fields and golf courses are big contributors to stormwater runoff and pollution. Rainwater runs off of turf nearly as quickly as it does pavement -- picking up chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides along the way. For turf areas, you would not use permeable paver filter strips, but you could certainly use bioswales and rain gardens to slow down and clean the stormwater and to keep more of it from running off site. You can even use this approach to manage rainwater that runs off of the roofs of buildings and structures, which also contribute greatly to community stormwater problems. Much to Gain In addition to helping to reduce local flooding and increase water quality, there are a wealth of benefits to this new approach to stormwater management. They include the following. www.ILparks.org November/December 2006 23 your investment in sewer infrastructure will be reduced, possibly eliminated. Filter strips, underground reservoirs, bioswales and rain gardens can take the place of costly curbs and gutters, catch basins and sewer pipes. You also save on maintenance costs over the long term. Native plants -- the prairie, wetland and woodland plants that are original to the Illinois landscape -- are particularly adapted to the growing conditions here. That means, once they are established, they require considerably less overall maintenance than other planted areas. What to Consider There are a few things to keep in mind if your agency is considering incorporating a more environmentally friendly approach to stormwater management. Remember that this approach is a departure from traditional ways of managing stormwater. While the basic engineering principle is the same -- water is channeled away from an impervious area and detained to keep a certain amount of stormwater on site -- the tools are different. Permeable pavers, underground reservoirs, bioswales and rain gardens replace catch basins, pipes, curbs and gutters. The more agency personnel can commit to using a naturalistic philosophy, the more successful the project will be. Such a commitment may ultimately spread to other practices in your agency, such as whether you use standard (chloride-based) salt in winter to de-ice paved areas or more environmentally friendly alternatives like potassium-or corn-based de-icers. Along those lines, be sure to engage your entire planning team from the outset of your project. Bringing personnel who will be involved in the project -- your architect, landscape architect, civil engineer, contractors and even community representatives -- to your pre-design meetings can only further the project's financial and functional success. Whether you use a more environmentally friendly approach to stormwater management or a traditional one, you still need to meet the same building code mandates. Your project will benefit when officials understand early on that you are meeting or exceeding water retention requirements. It is also helpful for them to become familiar with

www.ILparks.org November/December 2006 24

your new system -- and be able to provide input into its design early -- to facilitate approvals later on. Lastly, there are maintenance considerations. Once plants in the bioswales and rain gardens are established, they will be virtually maintenance free. This usually takes about three years. Until then, they will require weeding, the use of spot herbicides and possibly watering to help establish healthy root systems and to keep non-native plants from invading. From ephemeral streams to human-made bioswales and rain gardens, modern engineering imitates nature in stormwater management -- with notable results. Geoff Deigan is president of WRD Environmental, a Chicago-based ecological consulting firm that designs, installs, manages and consults on landscape projects and programs that conserve natural resources, promote sustainability, cultivate biodiversity and restore nature's balance. Visit www.wrdenvironmental.com. You can reach Geoff at 773.722.9870. www.ILparks.org November/December 2006 25 |

|

|