|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

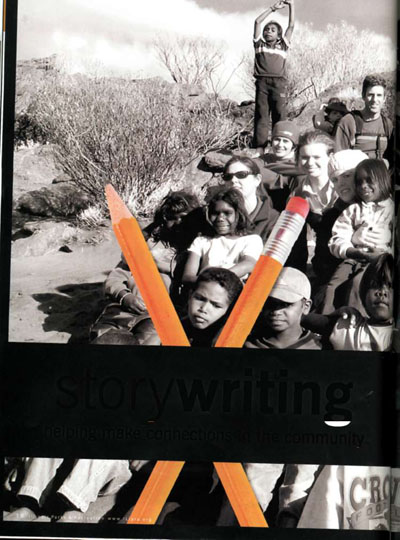

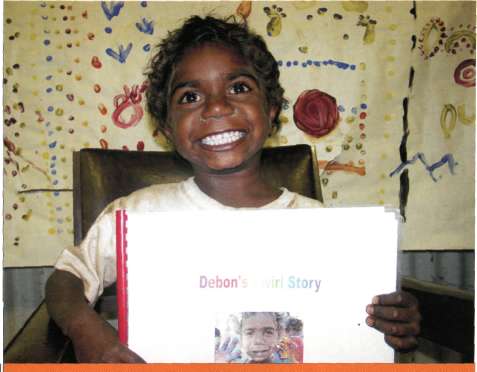

story writing helping make connections in the community by Jo An M. Zimmermann, Ph.D., CPRP, and Lawrence Mahon Many recreation programmers struggle with how to attract participants from the various cultural and ethnic groups in the communities where they work. A program offered in Australia to isolated indigenous communities may hold the key. 18 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org Letting Stories Arise From Cultural Connections SWIRL (Story Writing in Remote Locations) is a month-long day camp program that allows children to take part in activities and then document the experiences in booklets and other media such as video, animation, artwork and photographs. Children take part in activities planned by university student leaders that include traditional camp activities, such as games, crafts and sports, as well as culturally specific activities.  For Australian ethnic groups, these types of activities might include: bush tucker hunting (tracking wild game and searching for edible plants); popular Australian sporting pursuits (Aussie rules football, cricket, basketball, downball and soccer); culturally specific artistic endeavours (painting, dancing and music); and ethnic cooking. The university students take photos during the activity and then work in small groups or one-on-one to write stories in the children's words about what is happening in the pictures. The stories are documented in English and the child's own language, recorded with computer, digital camera, video, audio recording, artwork and clay animation. Each child thus has his or her own story as a printed, laminated and bound book and perhaps has a digital version of the story as well. This can be shared with family and friends. Copies are given to the local school libraries in an effort to increase culturally appropriate and child-friendly literature. SWIRL offers a window onto the daily life and social structure of these remote communities and their inhabitants in a way that would otherwise be impossible. The stories the young indigenous people tell through their creation of digital books introduce them to new media and its possibilities. At the same time, making these stories reinforces the children's sense of belonging to their culture. Debon shares her finished story. In Australia, the indigenous cultures are the ones that are in the minority, and they may be in danger of total assimilation. In Illinois, however, an increase in the number of people from minority cultures can make a story program like SWIRL a viable and socially relevant addition to your agency's programming - especially for those programs aimed to reach out to historically under-served populations. Urban Illinois has long been culturally diverse. But census data show that multicultural layers are covering the entire state. To cite one example, the Hispanic population of Illinois increased 69 percent between the 1990 and 2000 census counts. By 2000, Latinos comprised 8A percent of the total population of McHenry County; 10.5 percent of Will County; 10.8 percent of DuPage County; 16.8 percent of Lake County; 26 percent of Cook County and a hefty 27.8 percent of Kane County. Proportionately, pockets of downstate Illinois have seen even sharper up ticks. In Cass County, the Hispanic population grew from 56 people in 1990 to 1,106 by 2000 (a 2,000 percent increase), as a meat processing plant employing 1,800 people opened in Beardstown. Although Illinois minority children may be much less geographically isolated from the dominant social culture, the children of Illinois immigrants from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba and Central and South America likely have as many tales to tell (and as many customs to keep) as the Aboriginal children of Australia. A story writing program at your agency could be the means of keeping a cultural heritage alive and providing valuable social interaction at the same time. Know the Community and Gain Their Acceptance In Australia, because of the distance involved in working in remote communities (some are up to a seven-hour drive from a regional town), the SWIRL team moves into the community for the duration of the program. This gives the team ample opportunity to get to know the people in the community and build up trust with both children and elders. Programs are generally planned to take place starting at 9:00 or 9:30 until noon and again at 1:00 or 1:30 until 4:00, Monday through Friday, although a timetable is not strictly followed. The program is flexible so that it can accommodate the changing interests of the children and incorporate cultural activities with elders as the opportunity arises. Many of the university students who live a short time in the community continue to interact with the children after the program has ended for the day, joining them in a game of softball or soccer or even attending a community disco in the evening. The university students develop strong bonds with the community and many stay in contact

20 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org via e-mail for a long time after the program ends, with approximately 10 percent of all the university student participants returning to teach in the community they attended as soon as they graduate. In Illinois, traditional park agency users (teenagers, college students or interns) can become facilitators for your program and serve the same functions that the university students serve for the SWIRL program in Australia. Of course, in Illinois the physical distances between the facilitators and the potential child storytellers may be a matter of a few blocks, so total emersion in the minority culture is impractical. But the facilitators should be people who can bridge gaps. Obviously, the facilitators must be adept at using whatever media you are choosing to use to record the children's stories. They must be able to help the children learn to use audio, video, computer graphics, or even be able to help them construct sentences. But technical skills are only part of the package. Your facilitators need to be able to (and worthy enough to) gain the trust of the children and their guardians. If you are seeking to work with a minority population that speaks another language, bilingual facilitators may be valuable but certainly not necessary. A facilitator who is willing to show give and take by allowing the children to teach her (and watch her struggle with) phrases from another language and culturally diverse games and activities may be one who is able to connect with the students and draw out their stories in a meaningful way. The most important attributes are an open mind, a willingness to learn about another culture, to try new things, to go outside their comfort zone, and to be able to work in multidisciplinary teams comprised of, for example, educators, social workers, recreation leaders, technology specialists and others. Tips For Getting Started Remote Indigenous communities in Australia may be a long way from where you live and work, but the program itself and the lessons learned may be helpful for programming in multi-cultural and minority group environments. There are several key lessons to consider: 1. Take time to build relationships. The leaders within the community may not know whether the agency and the program can be trusted. You must reach out and develop those links - not expect them to come to you. 2. Consider partnering with a school or church. By choosing a site that children and families are already familiar with, you will lessen the fear of a new experience. Make plans with the partner organization to use space and also celebrate the successful writing of stories. Have a sharing night or a display or some other type of activity. You may also want to arrange to have copies of the stories given to the partner organization, but you may need to follow strict community protocols, which, in the case of SWIRL, includes acknowledging that ownership of all products of the program belong to the community. 3. Involve the entire community. The SWIRL program is open to people of any age who wish to be involved. By encouraging parents, siblings, grandparents etc., you will be demonstrating that you are responding openly to community interests. 4. Ask leaders of the community to contribute to the program. At SWIRL, the elders are encouraged to join the program and share their culture with the university students, as well as with the children. By seeking this type of involvement, you are showing respect for the culture. You may also be providing additional ways for children to learn more about their culture and/or share it with others. The sharing experience can lead to children taking pride in their culture. 5. Be flexible. Realize that everything does not need to be planned to the minute. Be ready to take advantage of sharing as the opportunity presents itself. 6. Allow the writing of stories to promote learning and sharing. One of the reasons SWIRL was developed was to help with poor literacy skills among the children in remote communities. Over eleven years, SWIRL has built up a collection of many hundreds of indigenous children's stories. These can be used as teaching aids for local schools. And as the children are learning language, they are also learning about their own cultural stories and processes that might otherwise have been lost. There may be children in your community who have English as a second language and therefore may struggle in school. By helping them to write stories in their words, you help them connect their culture with the community they now live in. The product - their book, video or Web site - also provides something they can share at home and school that demonstrates new knowledge and helps promote pride in accomplishment. 7. Remember that the program doesn't need to be expensive. You will need staff members who are enthusiastic about working with all ages and about learning a new culture. The students who went on SWIRL all volunteered their time. They were given transportation and accommodation, but paid for their own food. You need a space to hold the program and equipment. SWIRL had  Zowie, a university student, assists Cathryn with creating her story on the computer. 21 www.ILparks.org July/August 2007 two or three computers at each site with PowerPoint capabilities, the ability to download and manipulate digital photos and a microphone to make talking books; a printer; a laminator; scissors or a paper cutter; and a hole puncher. Each staff person was asked to bring his or her own digital camera, and photos were downloaded regularly for use in the books. We also had typical arts and craft supplies and sports equipment. Food for cooking projects was purchased locally as it was needed. 8. Start with what the children know. The very fact that SWIRL recognizes the value in children's diverse day-to-day activities as a vehicle for learning literacy skills helps us all gain deeper inter-cultural awareness. No one seems to return from a SWIRL experience the same as they left. Make the Connection A story writing program might offer your agency another method for connecting with people in your community. It promotes sharing, learning and, most of all, trust. If you develop trust with a new sector of your community, they more likely will be willing to participate in other programs offered by your agency. As they say down under, "Give it a go." The results will be awesome. Dr. Jo An M, Zimmermann, CPRP, is an associate professor in the Health, Physical Education, and Recreation Department at Texas State University-San Marcos. She has a bachelor's degree from Western Illinois University, an MBA from Olivet Nazarene University and a PhD from Clemson University. She has worked at Victoria University in Melbourne, Australia for four years and was an academic advisor at one of the SWIRL locations in 2006. Lawrence Mahon has been the coordinator of the SWIRL program since it's inception in 1996. He began the program as a way to address poor literacy skills among Indigenous Australians in remote regions. He teaches in the School of Education at Victoria University. About SWIRL SWIRL operates in partnership with Victoria University and a number of key stakeholders that include the Aboriginal communities; IBM; the Northern Territory Government, including the Department of Education; and local teachers and schools in Australia's Northern Territory. The SWIRL team ensures that community elders are involved in overseeing the programs, and their attendance on bush trips is encouraged. In this way, local elders feel connected to the aims of the program and also feel valued for the knowledge that they contribute to the program. For more information on the SWIRL program, contact the program coordinator Lawrence Mahon at: Lawry Mahon 22 Illinois Parks & Recreation www.ILipra.org |

|

|