|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

H. Roger Grant

Although Illinois could not boast having the first steam-powered railroad in the United States or the Midwest (Maryland in 1828 and Ohio in 1836 claimed those honors), residents could brag of being the home state for some of the earliest American carriers. On November 9,1838, a tiny, wood-burning locomotive, the Rogers, chugged and clanked over the fragile iron-capped rails between the village of Meredosia, located on the Illinois River in Morgan County, and what was then the end of the track at Dickinson Lake, eight miles to the east. The Rogers was the first train in Illinois and the first train to be operated by the Northern Cross Rail Road, a future unit of the Wabash Railroad and today part of the sprawling Norfolk Southern Corporation. Unlike later railroads in Illinois, private entrepreneurs did not develop the Northern Cross. Rather, the state sponsored this project, which was expected to be part of an extensive network of railroads that would connect mostly "inland" communities with usable waterways. Lawmakers realized that their fellow citizens wished to reduce their isolation, and the recently introduced railroad, although hardly perfected, offered a possible remedy. Admittedly, geography blessed portions of the state with several navigable rivers, including the Illinois, Ohio, and Mississippi. Illinois had access to Lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes, and the terrain in some areas favored construction of long-distance canals, which in the 1830s remained popular in parts of the nation, especially nearby Indiana and Ohio. Sailing vessels and better-designed steamboats were doing much to reduce the "tyranny of isolation." Nevertheless, vast sections of Illinois were remote from any natural or possible artificial waterways. By the 1830s and 1840s, good roads remained rare, with many settlers forced to use trails that originally had been fashioned by wild animals or Indians. 2

These public arteries were occasionally improved with broken pieces of rock or crudely cut halves of trees or rough-hewn wooden planks that at times magnified "bumpiness" for users. While travel conditions in the winter might be acceptable when the frozen and snow-covered ground permitted usage of sleds and sleighs, other seasons brought "freshets" and floods, muddy ruts, and choking dust. In 1837 the legislature, encouraged by Governor Joseph Duncan, took action. The body overwhelmingly endorsed "An Act to Establish and Maintain a General System of Internal Improvements." This commitment, startling to some non-residents, prompted the American Railroad Journal to editorialize that it "must surely satisfy those who are still incredulous as to the high destinies of that young State." Part of the legislative response would be better water commerce, which led to the building of the ninety-seven-mile-long Illinois & Michigan Canal between Chicago (Lake Michigan) and La Salle (Illinois River), opening in 1848. Yet, in addition, the railroad would be the capstone of this grand scheme of transportation improvements.

The politicians of Illinois had big plans. Their act of 1837 called for massive and expensive railroad building. If implemented, more than thirteen hundred miles of track would be constructed at a cost exceeding $10 million. Specifically, the Central Rail Road would link Cairo, near the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, with Vandalia, Decatur, and Bloomington to a point at or near the terminus of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and northward to Galena, the center of the lead mining district, with a branch extending from Shelbyville to the Indiana border. The Southern Cross Rail Road would stretch from Alton on the Mississippi River to Mount Carmel on the Indiana border via Edwardsville and Salem with an extension to Shawneetown. Finally, the Northern Cross Railroad would run from Quincy through Meredosia, Jacksonville, Springfield, Decatur, and Danville to Indiana, where it would connect with what would become the nation's longest "ditch," the 468-mile Wabash & Erie Canal (1832-1874). The measure also designated other railroads to crisscross the state, including one from Bloomington to Mackinaw, where the line would diverge to Peoria and Pekin. Even though blatant political logrolling and sectionalism shaped the statute, there would be supervisory controls. The act created as part of an expanded state bureaucracy "fund commissioners," chosen by the legislature, who would raise the necessary investment money through sale of internal-improvement bonds. 3

These three "practical and experienced financier—qualities required by law—would work with seven commissioners of public works, who represented specific state judicial districts. Considerable optimism existed about implementing this 1837 internal improvement measure. Lawmakers and their supporters were well aware of the success of several states, most of all New York, in raising funds and successfully building hundreds of miles of canals. Even though railroads represented a fresh technology, both in Europe and the United States, they knew that South Carolina officials had been able to finance construction of the South Carolina Canal and Rail-Road. Completed in fall 1833, the 136-mile route stretched between the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston and the Savannah River at Hamburg, located opposite Augusta, Georgia. As with New York and South Carolina, Illinois enjoyed a strong credit rating, and outside investors, particularly in England and Holland, appeared eager to acquire the debt of American states. Slowly the Northern Cross expanded. In the fall of 1839 its flimsy rails, wooden with iron caps or "straps," reached Jacksonville. But the prospects of extending this pioneer pike worsened with the onset of hard times that followed the severe Panic of 1837. The depressed economy made it difficult for Illinois to sell bonds for any internal improvement project. By late 1840 railroad construction in the state had largely been suspended. Some residents along the proposed Northern Cross route, though, became lucky. Internal improvement advocates in the legislature argued effectively for the project's completion, at least to Springfield. When that happened, net revenues would surely cover most or all of the construction and operating costs. A majority of lawmakers agreed, and in 1841 a financial package was ready to be implemented. Before the end of the year the iron horse at last arrived in the state capital.

Although the Northern Cross had developed into a somewhat strategic railroad linking the Illinois and occasionally navigable Sangamon rivers and connecting Jacksonville and Springfield with steamboat connections at Meredosia for St. Louis and other Mississippi River destinations, the publicly owned property failed financially. To solve these money woes the state initially leased the railroad and then sold the line for a pittance. No longer did public sentiment exist for state-sponsored railroads. In time the Great Western Rail Road Company of Illinois used the old Northern Cross, reaching Decatur, Danville, and the Indiana state line. Later the road became part of the Toledo, Wabash & Western Railway, which by the Civil War had created a direct, through ironway between Toledo, Ohio, and the Mississippi River at Quincy, Illinois, and Keokuk, Iowa. 4

Even with the disappointment of the Northern Cross and other publicly proposed arteries, railroad fever resumed during the latter part of the 1840s with the return of a more robust national and regional economy. Residents of Chicago had

What became the first carrier in Chicago, the Galena & Chicago Union Railroad (Galena Road), started to take shape in the mid-1830s. But the scheme to link the lakeside community to the lead-mining region around Galena became only a "hot-air" proposition, adversely affected by the hard times triggered by the Panic of 1837. Then a decade or so later the dream began to become a reality when William Butler Ogden, Chicago's first mayor and a successful entrepreneur, and other business associates assembled adequate financing for construction of their privately owned Galena Road. In June 1848 the building process began when 5

workers drove the first "grade pegs" near the corner of Kinzie and Halsted streets on the outskirts of Chicago. It was not long before cheap strap-rail track appeared, extending by that autumn to the Des Plaines River, near presentday Maywood. Even though the railroad never reached Galena, by the early 1850s track linked Chicago with Elgin and Rockford. Unlike the state-sponsored Northern Cross, the Galena Road became a solid money-maker and attracted ample investment funds to the company and, after 1859, to its expanded system, the Chicago & North Western Railway (C&NW). By the 1860s the C&NW sported state-of-the-art equipment, solid iron rails, and even sections of double-track. An image emerged in the 1850s (at least prior to the serious, albeit brief Panic of 1857) that Illinois would be a smart place to promote railroad projects. Also, railroads had become attractive investments. The "demonstration period" of the 1830s and 1840s had given way to a proven technology capable of serving most places with dependable, all-weather service. By the eve of the Civil War railroad mileage in Illinois had increased enormously. In 1850 there had been only 111 route miles; a decade later residents enjoyed a network, although somewhat unconnected, of 2,790 miles, representing a whopping increase of 2,413 percent. Instead of a single carrier—the Galena Road that served Chicago—there were now eleven, and the rapidly growing city was well on its way to becoming the nation's railroad Mecca. The accomplishments were remarkable. Boston capitalists had pieced together the more than two-hundred mile Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), and another group of promoters had built the largely parallel Chicago & Rock Island Railroad, a road remembered for installing the first railroad bridge across the Mississippi River in 1856. Indeed, a famous controversy arose between the Rock Island Railroad and steamboat interests over obstructing river navigation, which led to a lawsuit won by the railroad with the legal assistance of lawyer Abraham Lincoln. But the grandest project in the state was the Illinois Central (IC). During the pre-Civil War years the longest and arguably the most important railroad in the Midwest was the IC. Unlike the gestating Galena Road, CB&Q and Rock Island, the 705-mile IC was a north-south line that extended the length of the state, connecting Dunleith (opposite Dubuque, Iowa) on the Mississippi River with Cairo on the Ohio River near the stream's mouth. The company also installed a 252-mile "branch" that connected Centralia, approximately one hundred miles north of Cairo, with Chicago, and in time this trackage became the principal route of the IC. An important factor in explaining the rapid and exceptional growth of the IC was that U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois helped to push through Congress the first major land-grant act that directly aided railroad construction. The law, passed in 1850, gave to the IC six alternate sections of land for each mile of line built, and soon the company was selling at a good price this often incredibly rich prairie land to an array of new settlers. "Illinois is known throughout the United States as the Garden State of the Union, and from the extraordinary fertility of its soil, is justly entitled to the name," proclaimed an 1856 promotional booklet, The Illinois Central Rail-Road Company Offers for Sale Over 2,000,000 Acres Selected Farming and Wood Lands ... On Long Credits and at Low Rates of Interest. Differing dramatically from the Northern Cross, ample funds flowed into IC coffers for construction and operations. By 1860 even the casual observer sensed that the railroad had become a modern "magic carpet." Chicago was becoming the greatest city of the Midwest, surpassing the older and largely river-dependent Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis. Chicago was a bustling metropolis of 109,000 residents with more than one hundred passenger trains arriving and departing daily, and it was a place cluttered with factories, granaries, warehouses, and businesses of all sorts. Much to the sorrow of urban rivals, Chicago had established itself as the major western terminal of the East and had in the words of Horace Greeley its "long iron arms extending far into the productive West." Although Ilinois had been in the union since 1818, railroads did much to stimulate statewide town-making and agricultural development. Scores of communities from Turner Junction (later renamed West Chicago) to Centralia owed their existence to the coming of the iron horse. Farmers now could become oriented toward commercial markets, abandoning the earlier practice of semi-subsistence agriculture. And the population of Illinois reflected these dramatic changes: 476,202 in 1840; 851,470 in 1850; and 1,711,871 in 1860. The state was well on its way to greatness.

Overview Main Ideas 6 emergence as one of the most important cities in the United States in the latter half of the nineteenth century, was due to the railroad. Chicago was the city at which almost all trains traveling from the East would need to stop. Chicago, consequently, became an industrial and agricultural center, its trains laden with goods from across Illinois and the Midwest, bound for locales all over the burgeoning United States. But railroad growth in Illinois was sporadic and suffered from a very slow start. By 1848, there were only two railroads in the

One man was most responsible for this growth: Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Not only did he convince Congress to transfer lands in the state for railroad building, his efforts resulted in the building of the Illinois Central Railroad, which was the world's longest railroad at the time. By 1856, the Illinois Central Railroad traversed the length of the entire state, from the northwest corner all the way to the banks of the Ohio River. A line of the Illinois Central also extended to Chicago. Eventually, the Illinois Central Railroad grew beyond the borders of Illinois and connected to New Orleans (Louisiana) in the South and Omaha (Nebraska) to the West. The railroad transformed Illinois. The railroads' presence not only aided the growth of industry, but agriculture in this state grew as well with development of the railroad. Land was cheap, and the ability to quickly transfer grain and livestock to market proved to be a great incentive for farmers wishing to take advantage of the rich prairie soil. By the turn of the twentieth century, Illinois had one of the most complete railroad networks and perhaps the best service in the entire country. Connection with the Curriculum Teaching Level Materials for Each Student Objectives for Each Student

Opening the Lesson Developing the Lesson

7

Activity Two: Students can work individually on the assignment or in small groups. This activity highlights the Effie Afton case. In 1856 a steamer,

Concluding the Lesson Extending the Lesson Assessing the Lesson

Accuracy of the answers for each activity.

8

1. On your blank map, identify the following cities:

2. On your blank map, identify the following rivers:

a. Northern Cross Railroad. This was the first railroad in Illinois. Although it initially was only some twelve miles long, eventually it

b. Galena & Chicago Union Railroad. Although this railroad never made it to Galena, it was a very popular railroad that

c. Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad. This railroad began operation in 1849 and became only the second railroad

d. Alton and Chicago Railroad. This railroad was originally chartered to connect Springfield to the Mississippi River via Alton, Illinois.

e. Chicago & Rock Island Railroad. The first train traveled this rail in 1852. Connect Rock Island to Bureau/Peru. Then continue the line to Joliet

f. The Illinois Central Railroad. After its completion, the Illinois Central Railroad was the longest railroad in the world. It not only connected the northern and 9

10

Read each newspaper excerpt below and then answer the questions.

11

12

Answer the following questions: 1. When was the railroad bridge completed? 2. According to the first article, why is this bridge so important? 3. How much space does a boat have to navigate in the main channel under the bridge? 4. What was the Effie Afton? 5. What happened to her? 6. Why was a lawsuit brought by Effie Alton's owners? 7. What notable person helped in the defense? 8. Summarize the arguments of the Plaintiffs. 9. Summarize the arguments of the Defendants. 10. What economic issues were represented by this case? 11. Based on the limited information presented here, who do you think should win this court case? Explain. 13

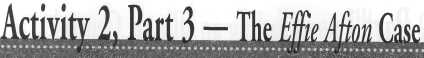

Reading an Illinois Central Train Schedule. Examine the following schedule very carefully and answer the following questions.

14

Reading an Illinois Central Train Schedule. Using the timetable, answer the following questions. 1. How many miles is it between Chicago and Cairo? 2. Where does this branch of the Illinois Central Railway connect with the main branch of the line? 3. How far do the passenger trains travel on the line? 4. If you left Cairo at 4:15 A. M., what time would you reach Chicago? 5. If you took the 9:20 train out of Chicago, where would you be around noon the next day? 6. How many miles is it from Cairo to Champaign? 7. How many hours is it from Chicago to Cairo via the Mail train? 8. At this time in the railway's history, if you wanted to get to Mississippi or Alabama, what would you have to do? 9. How many stops are on this line? 10. How much is it to travel the entire length of this line? 11. Based on the mileage, approximately how much would it cost for a ticket from Chicago to Champaign? 15

16

Activity 2, Part 3

1. April1856 Activity 3, Part 2

1. 365 miles 17 |

|

|