North Shore

|

BY CLARICE STETTER: A lifelong resident of the North Shore area

of Cook County, she edits the Illinois

Voter for the League of Women Voters and

has worked part-time for the

Suburban Tribune. She has a master's

degree in journalism from

Northwestern University.

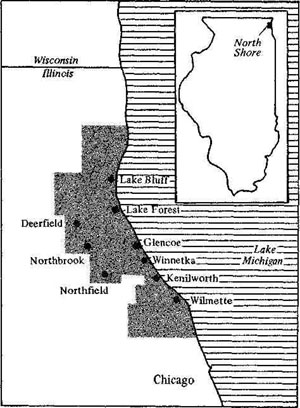

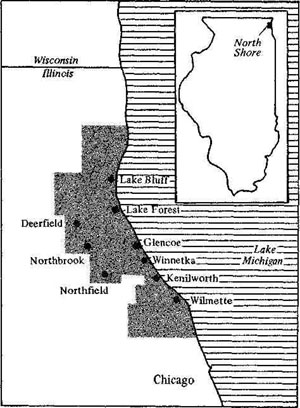

'Caucus system' flourishes on the North Shore

Local officials in eight

Chicago suburbs are

nominated through a

nonpartisan process which

solicits the views of

residents and culminates in

an annual town meeting.

The nominating process

works so well that voter

turnout in elections

is usually poor

OLD-TIME ME party politics, as we ail

know, are alive and well in Illinois. But

coexisting with the old politics is a

nonpartisan method of selecting municipal candidates called the caucus system.

This political system operates successfully in several suburbs along Chicago's

affluent North Shore. The municipal

caucus method, which is based on the

philosophy that "the job seeks the man,"

has been functioning for over 50 years

and its candidates will win many local

elections in April.

The eight suburbs presently using this

system vary in population from North-

brook with 27,681 residents to tiny

Kenilworth with 2,980 residents. Three

of the suburbs, Winnetka, Kenilworth

and Glencoe, are old established villages

whose populations and boundaries have

changed little during the past 20 years.

Lake Bluff and Lake Forest, also old

North Shore communities, still

|

have some land expansion possibilities to the

west. Northfield, Northbrook and

Deerfield, lying inland from Lake

Michigan, are more recently developed

communities and still have both

population and land expansion potential.

The residents of all eight suburbs are

above average in education levels and

per capita income, according to 1970

U.S. Census figures.

Each of the communities has taken

the concept of a nonpartisan caucus

system and adjusted it to fit local needs.

In one form or another, the system has

operated on the North Shore since it

began in Winnetka in 1917. The caucus

idea soon spread to Glencoe, Lake

Forest and Lake Bluff and later, westward to the newer suburbs of Deerfield,

Northbrook and Northfield.

Each year following the local

elections in April, a local caucus begins

anew with different members and a

different name, i.e., "The 1974 Caucus"

or "The 1975 Caucus." The process

consists of interviewing and selecting

candidates, but it does not lead to a

primary election. If a caucus operated as

a continuing political party, a primary

election would be required by state law.

Seven of the eight communities determine

caucus representation on a geographic

basis either by appointment or

election at the precinct level. Individual

precinct representation varies from

three to eight members depending on

the community. Full caucus membership

varies from 27 in Northfield to

more than 70 in Winnetka. Bylaws set

staggered terms and provide for 1/3 to

2/3 of each caucus to be replaced each

year. Kenilworth is the only community

which bases its caucus on organizational

representation. Twenty-three civic

organizations send two delegates to the

Kenilworth caucus. Caucus bylaws also

provide for delegates-at-large if an

individual has obtained signatures from

25 residents.

Preparing for an election

A caucus may have an "on and off

year depending on duties of the caucus

and the election calendar under which

that community operates. Caucus systems

in Kenilworth, Winnetka, Glencoe, Northbrook and Lake Forest are

responsible for the selection of candidates for village (Lake Forest has a city

council), park, library and school

boards. The village caucuses in North-

fieid, Deerfield and Lake Bluff are not

responsible for proposing school board

candidates and were dormant this past

year. The next village election in these

communities is in April 1977.

Caucuses preparing for this April's

local elections began work last summer

by compiling village concerns and

soliciting names of potential candidates

from local residents through villagewide

mailings and public meetings. The

Winnetka Caucus Committee sent a

10 / April 1976 / Illinois Issues

detailed questionnaire to ail residents

asking specific questions with regard to

each elected board in the village. The

caucus then developed a platform based

on a 26 percent response rate to the

questionnaire. Although no other community

has the sophisticated questionnaire method

used by Winneika. caucuses in Glencoe.

Northfield and Northbrook do solicit citizen views on local

issues in preparing a caucus platform,

All caucuses provide for individual

interviews with possible candidates, in

some communities, subcommittees

interview candidates and report

recommendations to the total caucus, in some

cases, the entire caucus commit

interviews each candidate.

Many residents see community service as

one of their village responsibilities

and volunteer to serve on a local

board. Last fall, the Winnctka caucus

interviewed 40 candidates for four

openings on its village council. The

Glencoe caucus interviewed 17 for its

four village board vacancies. Questions

put to the candidates ranged from

"When did you last attend a village

board meeting?" and "How many hours

do you think the job of trustee entails?"

to asking for specific views on a local

zoning or land use issue. Generally,

caucus interviews consider a candidate's

education, work experience

and background in community service more

thoroughly than his views on a specific

issue. But caucuses have been known to

reject a qualified candidate because he

spoke out strongly on a highly controversial local concern.

After the initial interviewing is completed, the full caucus may accept the

subcommittee's recommendation, or it

may decide to interview the finalists

again before voting. Usually a 2/3 vote

by the full caucus determines the slate

that will be presented for ratification at

a town meeting.

The town meeting, which usually

fakes place in late January or early

February, resembles in spirit the

meetings which have been taking place in

many New England towns for more

than three centuries. However, these

meetings in the North Shore communies

exist by virtue of caucus bylaws;

they are not official bodies and should

not be confused with the statutory

meetings of township governments

which also exist in Cook County outside

Chicago and in 84 other Illinois counties.

Except for Kenilworth, where only

caucus members may vote in the town

meeting, village residents confirm

caucus slater and. in effect, determine

the future course of their village. In an

uneventful year. only a few hundred

residents will attend a town meeting

although all caucus bylaws make

detailed provisions for advanced publicity

of the meeting date. Public interest in

the town rneeting can change in a year

when issues or candidates become

controversial. More than 1,500

residents attended Northbrook's town

meeting in January, some arriving by

chartered bus — quite a change from

previous years when attendance was

four to five hundred. Residents at that

town meeting altered the caucus slate

which they felt had omitted a particularly

able candidate for village trustee.

|

The caucuses and chairmen

Donald Hoover, Jr., chairman

Deerfield Caucus Plan

Ira Weinberg, chairman

Village Nominating Committee,

Glencoe Caucus Plan

Robert Balsley. chairman

Kenilworth Citizen's Advisory Committee

Donald H. MacKey, chairman

Lake Bluff Progressive Party Advisory Committee

Thomas E. Donnelley, II, chairman

Lake Forest Caucus

Jane Staley, chairperson

Northbrook Village Caucus

David Mason, chairman

Northfield Village Caucus

John Clark. chairman

Winnetka Caucus Committee

|

|

Town meetings in other communities

have also. in some instances, rejected a

recommended candidate and slated

someone nominated from the floor,

usually a person interviewed by the

caucus, but not a finalist. Most caucus

communities and town meetings look

with some suspicion on a new candidate

who has not presented himself to the

caucus for interviewing. In Glencoe,

participants at a town meeting can

refuse to ratify the proposed slate and

direct the caucus committee to report

back to another town meeting with a

different slate. Whether a town meeting

is a poorly attended event or a highly

charged meeting lasting until 2 a.m., the

majority of residents at the meeting determine

the caucus party slate to be presented to the

voters at the April elections. The caucus then proceeds with the

legal necessities of circulating and filing

petitions, publicizing candidates and the

upcoming election and, finally,

campaigning for its candidates if the caucus

slate is contested at the polls.

Municipalities are subject to the

Election Code, and the petition, as

provided in Article 10 of the code, is the

usual method of placing candidates'

names on the ballot. The way is left

open, of course, for an opposition group

— and this did happen, as noted below,

in Wilmette several years ago. The

caucus method is not, of course, a true

nonpartisan system because candidates

run under the label of a local party —

although not using the names of existing

statewide parties. It is, correctly, a form

of one-party system, but with a "new"

party name each year to avoid the

primary election required for established parties.

With crises occurring at every level of

partisan politics, caucus supporters

point to definite advantages of the

nonpartisan caucus system. It offers the

opportunity for wide citizen participation

in the nominating process. Caucuses

interview all persons expressing

interest in serving on a local board, and

caucus members take seriously the

responsibility for soliciting names from

the community.

|

Perhaps the most obvious advantage

of the caucus system is that it eliminates

the need for an expensive, time-

consuming and divisive campaign.

When the conscientious delegates of a

broadly based caucus do a good job of

candidate selection, the best available

people can be slated to serve. The

responsibility for publicity and financing

rests with the total caucus and not on

the shoulders of individual candidates.

Caucus supporters believe more qualified

and dedicated people are willing to

volunteer for noncompensatory board

service under these circumstances.

Finally, proponents of the caucus

system say that a nonpartisan, communtywide caucus allows for local issues to

be considered in a rational manner

April 1976 / Illinois Issues / 11

In one recent election for village president only 50 votes

were cast. A resident of that village said, 'Its scary to think

that a carefully concealed write-in campaign could have

easily elected someone else'

— villagewide surveys, early public

meetings or caucus representation.

Caucus critics say the caucus method

has drawbacks that are inherent in the

very nature of the system. Heavy

committee work, late meetings and time

commitments extending over a number

of months put demands on a caucus

member that many people refuse to

accept, and therefore, some caucuses are

not at full delegate strength as designated

in local bylaws. In addition, the

possibility always exists that a caucus

may be dominated by a particular

interest group. New residents may be

confused by the system and take longer

to get involved than long-time residents

who are familiar with the caucus system.

Every caucus community also remembers

a year when people "came out of the

woodwork" to serve on the caucus

because they were interested in a single

local issue.

Although a variety of special interests

represented by caucus members may

encourage good discussion at caucus

meetings, critics say once a slate has

been accepted by the caucus, the fact

that it is a single slate may preclude the

discussion of local issues in the wider

community. Sometimes the town meeting

at which candidates are presented

and ratified may be the scene of public

debate, but decisions made at that

meeting end community discussion.

Seldom do candidates debate issues at

candidates' meetings or in the press

before an April election unless that

election is contested. Consequently,

voter turnout in caucus communities is

often poor during an uneventful year.

Communities with registered voters in

the thousands will turn out a couple of

hundred voters to reaffirm the caucus

slate.

In one recent election for village

president only 50 votes were cast. A

resident of that village said, "It's scary to

think that a carefully concealed write-in

campaign 'could have easily elected

someone else." Another resident noted

with some embarrassment that the 50

votes cast were less than the full caucus

delegation, which meant that not even

all caucus members had remembered to

support the slate on election day. But if

there is a choice of candidates or a

controversy, the voters do turn out. In a

1971 election in the small community of

Lake Bluff which had supported a

caucus system for 40 years, 60 per cent

of the 2,500 registered voters turned out

to vote on a contested slate. Previously,

Lake Bluff local elections attracted 10

per cent of the voters. After the 1971

election, residents were sufficiently

concerned about the health of their

caucus that opposing factions worked

out by law changes to the satisfaction of

both sides. Currently, the uncontested

elections in Lake Bluff once again

attract 10 per cent of the potential

voters.

In most other caucus communities a

caucus challenge comes at the town

meeting rather than at the polls. Proponents

and opponents of a candidate

or issue will get their supporters to the

meeting and decisions at the town

meeting will usually settle the matter. If

a candidate recommended by the caucus

is dropped at the town meeting, that

normally ends the matter. Unsupported

candidates usually feel that to file and

run as an independent would threaten

the existence of the caucus. In the few

instances when a candidate has chosen

to ignore the caucus and run outside the

system, he or she is usually defeated at

the polls. On the other hand, if an

"outsider" is elected and the caucus

candidate is defeated at the polls, the

caucus is not seriously damaged.

Instead, the defeat may be used as the

impetus for examination and perhaps

modification of the caucus system to

better deal with the changing needs of

the community.

Wilmette, another North Shore suburb

(population 32,134). is an exception

to the traditional growth and strength

of an established caucus system. In

Wilmette, a 30-year-old caucus blew

apart in 1969 when a serious split

developed in the caucus. In reviewing

the proposed slate for that year, it

appeared to a group of old-time

residents that a younger, possibly more

liberal group, had seized control of the

caucus and ignored certain candidates,

including incumbents. Unlike its sister

suburbs, Wilmette caucus bylaws did

not provide for a town meeting. The

older dissident group withdrew from the

caucus before the final caucus meeting

and presented their own slate to the

electorate.

This contested election resulted in

such an overwhelming voter turnout

that the polls were unable to handle the

volume, and a federal court required an

election rerun due to voter disenfranchisement.

The insurgents' slate won

both elections. If Wilmette caucus rules

had provided for a town meeting this

split might not have occurred. To date,

caucus supporters have been unable to

reestablish the system in Wilmette.

In contrast, heated debates at 1975

Northbrook and Deerfield town meetings

and this past January in Glencoe,

threatened, but did not shatter, local

caucuses.

A venerable tradition

Caucus observers list several reasons

for the durability of the system: (1) these

affluent suburbs have few real problems

causing controversy; (2) the highly

trained administrative village staffs

operate community services efficiently

leaving little for residents to complain

about; (3) the high level of competency

and integrity of the elected officials

negates charges of corruption and

inefficiency; and finally (4) village

residents believe there is not a Republican or Democratic way of street

maintenance and garbage pick-up and

don't want partisan parties "messing

around" in their local government.

Whatever the primary reason, it's

clear that the venerable tradition of a

nonpartisan caucus system for selecting

local office holders has outlasted special

interest groups, local causes and individual candidates and continues to

flourish on the North Shore.

12 / April 1976 / Illinois Issues