|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

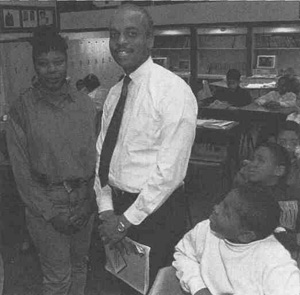

It was a bitter Chicago winter day in late January, and Calvin Gooch could have been watching a school official's nightmare unfold: An afternoon bus driver hadn't shown up, and dozens of grade-school students were stranded at their North Lawndale school.

Cold weather or not, the idea of children's walking home wasn't an option that excited Gooch, especially as the sky began to grow dark. The school sits in a neighborhood populated by gang members all hours of the day. Right across the street, a man was shot recently as he stood on the steps of Manley High School. Still, Gooch wasn't worried. As administrator of the privately funded Corporate/Community School of America, he has several options open in situations that would leave many public school officials wringing their hands and searching for answers through layers of rules and regulations. In this case, Gooch could have kept the kids at the school — it's open until 7 p.m. most evenings anyway. He could have called upon teachers to arrange carpools. Or he could have pulled his own Jeep out and shuttled them home himself.

"Whatever the community needs, we can meet," he says. That's his motto for the Corporate/Community School, which serves 300 students from preschool through eighth grade. "And what it needs is quality education in a safe environment." That means the school is open from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. to work around parents' job schedules. Classes run 11 months of the year. If school officials decide the school should be open until 10 p.m. or midnight 12 months a year, they can make it happen. The school receives no public money, so it sets its own policies. That means selecting or changing classroom curricula whenever necessary. It means hiring teachers the school deems qualified — whether they have state teaching certificates or not. And it means firing teachers without batting an eye over stringent tenure requirements if they aren't meeting expectations. No regulations to follow or circumvent. No duplicative forms to fill out and pass along. No hoops to jump through. These are some reasons the Corporate/Community School is considered by some as a model for charter schools — the most celebrated education reform idea around these days. Already approved in eight states, charter schools receive state funds but are freed from most state restrictions. Supporters tout 20/March 1994/Illinois Issues

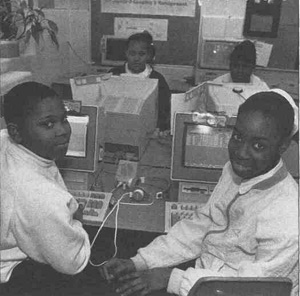

Once the charter is approved — usually by a local school board — the group either converts an existing school or sets up an entirely new one. Charter schools generally receive the same amount of state money per pupil as other public schools in the district. They are held to only the most basic regulations, such as nondiscrimination practices, nonreligious curricula, open enrollment and standard safety codes. In deciding whether to legalize these schools in Illinois, one of the first things state lawmakers will have to sort out is exactly what constitutes a charter school. A wide variety of models exist based on laws enacted in other states. In Massachusetts, the state secretary of education can authorize charters to a range of different groups wishing to start a school, including businesses, two or more certi- March 1994/lllinois Issues/21 fied teachers, or 10 or more parents. This approach varies from the more narrow Georgia law, which allows a school to seek a charter from the state board of education only if it receives approval from the local school board, a two-thirds vote of faculty and instructional staff at the school, and parental support. And the philosophies driving existing charter schools vary as well, even in a single state. Cedar Riverside in Minneapolis, which serves 85 children from low-income families, was started to target students at risk of dropping out of school. Toivola-Meadowlands in rural northern Minnesota had a different mission: It was formed to avoid consolidation with another school, and now is a multi-age classroom school with an environmental theme. Another proposal in Minnesota would establish a school where students from ages 12 to 20 would design, build, market and sell wooden toys and crafts, learning basic and business skills in the process. "See, this is the kind of thing I'm talking about when I wonder whether these can be applied to all students," says Michael Skarr, who chairs the Illinois State Board of Education. On the other hand, if the state tries to avoid offbeat proposals and steer charter schools toward more mainstream curricula, it could find itself in a Catch-22; the whole point of charter schools, he says, is to strip away state involvement and limitations. This freedom from state regulations is key to fostering creativity in education, says Gooch. 'The best thing I've found about the Corporate/Community School is that we have the autonomy to make decisions without ever going outside the building," he says. "We don't have to get approval from different bureaucratic levels or teachers' unions. We can reevaluate and change curriculum as we see fit; we just consult with teachers and parents." Maxine Duster, the school's principal and a former teacher in the Chicago Public Schools, agrees. "We give our individual teachers freedom to choose their own materials, in essence so they can give their individual classes the specific kind of instruction they feel they need." There is reason to listen to what Gooch and Duster have to say. That's because the Corporate/Community School is about the best model for an urban charter school that's up and running in Illinois. It is funded largely by hefty gifts from wealthy sponsors (ranging from huge corporations to talk-show diva Oprah Winfrey), and spends nearly $6,000 per pupil — roughly the same as Chicago public schools, which is what a charter school in the city would receive for each student. Reflecting the make-up of the neighborhood in which it sits, the student population at Corporate/Community School is 99 percent African-American, one percent Latino, and almost entirely from low-income families. Students must live within certain geographical boundaries to attend, but otherwise there are no admission requirements. And no tuition is charged. Standardized tests were started only last year to track student achievement at the school, so no progress — or decline — has been documented so far. But one hint of success, Gooch says, is that all 16 members of the school's first graduating class were accepted into public academy-type high schools that offer specialized programs in various subjects, such as math and science, and have stringent admission requirements. Converted from a Catholic school no longer in use, Corporate/Community School doesn't look too different from other elementary schools in the city. True, it doesn't have the gang graffiti that decorates so many walls of the Lawndale community. But it doesn't have multitudes of high-tech capabilities in every classroom either. There is one computer in each class, plus two computer labs in the school, where neat rows of cream-colored terminals await students each day. Classrooms basically look unremarkable, equipped with the standard bulletin boards and bookshelves. What is remarkable is that students and parents are highly engaged in the education process there. Parents are required to volunteer five hours of time to the school each year in any of a number of ways — helping out in the classroom, in the after-school program (where participating students get most or all of their homework done) or doing something at home, such as sewing costumes for a school production. "This is the classic model of a charter school," says state Sen. John Cullerton (D-6, Chicago), an advocate of charter schools, who toured the Corporate/Community School recently. "They open enrollment for everyone, the teachers are paid well, and the [nearly $6,000 spent per pupil] is less than the state spends on Chicago students. The only problem is the teachers don't have a pension there." Even with the Corporate/Community School — or other school success stories — as models, some people wonder whether charter schools actually can be used to reform an entire school system. Skarr is skeptical. "It's tough to be against charter schools in concept — even for me," he says. "They're flashy, they're contemporary, they've got a lot of public relations appeal. But the jury is still out in terms of their value. The question is, are all of the students in Illinois going to be better off? I'm worried about the kids who are not going to be in charter schools. I want more widespread change." Ted Kolderie, one of the originators of Minnesota's charter school plan, understands the desire for formal large-scale reforms in education. But he thinks such efforts have almost become futile. "For a long time we've had a lot of people advocate general or systemic reform, saying that we've got to work with all fronts at once, help all students at once," says Kolderie, senior associate with the nonprofit Center for Policy Studies in St. Paul. "That obviously hasn't worked. If that argument were right, we'd be farther along with reforms than we are now." That's probably true. But then Skarr's state board colleague 22/March 1994/Illinois Issues

"Even if you do just fill charter schools with more motivated kids," he says, "you've got to have an affordable or free way to let low-income parents send their kids to better schools. That's what would be good about charter schools." What's more, says Kolderie, charter schools actually can move toward widespread change if they work as intended. "This is a way to get some dynamics going," he says of the schools. "It's not a pilot project in the old sense. Yes, we've had pilot stuff. But those don't push districts to change. The only thing that pushes them to change is seeing someone else doing it better with the same amount of money. "We had a standing offer in Minnesota for schools to seek waivers from state regulations, but no one comes in to ask for them," Kolderie says. "You need more than just the state's willingness to offer this. School districts just don't do much without a push from others — such as charter schools. As soon as charter schools were implemented, we started hearing: Why not charter districts? Why not charter all schools? Well, legislatures may be willing to do this, but that's because of the few that got the ball rolling." And now it's rolling in Illinois. But how fast this ball continues to roll here remains to be seen. There are significant political obstacles standing in its way. For one thing, in calling for creation of just a dozen charter schools, Gov. Edgar signaled he favors a cautious approach to the idea. Establishing a dozen charter schools would mean setting up a dozen more models of programs that have already shown they can work. Students who would attend those 12 schools undoubtedly would benefit from the academic freedoms and new ideas implemented there. But such a modest reform would leave untouched the vast majority of the more than 1.8 million students enrolled in Illinois public schools. They, instead, would continue to endure the educational status quo. Another barrier is the attitude of the state's education establishment, which has voiced some reluctance about charter schools. Some members of the state board, as Skarr and Gallagher suggest, are wary of the idea. And Bob Haisman, president of the Illinois Education Association, says his group is "somewhat fluid" on the concept of charter schools. "If we're talking about relieving teachers of burdensome bureaucracy and paperwork, we're going to be inclined to take a strong look at it," he says. But the union is steadfast on some key elements of the idea. "If we're talking about doing away with teacher certification requirements," adds Haisman, "we're against that. We'd like to see some things, like protections for teachers' jobs, written into the law. It makes us nervous to leave a lot of things up to individual charters." This sentiment, in a nutshell, may doom the idea of charter schools. The key to their success lies in the ability to make individual decisions, Gooch says. "The interesting thing is that our school is successful not because of legislation but because of its inhabitants — what we've decided to do here. I could take this group and these ideas and take it anyplace and be successful — as long as there are no restrictions," he says. This independence and grass-roots decision-making is essential if charter schools are to work in Illinois. Those who have tried it say the best thing for meddling politicians and hidebound education bureaucrats to do to keep the charter school ball rolling in Illinois is to step back and get out of the way. March 1994/Illinois Issues/23

|