|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Love and justice: Marital dissolution in antebellum Illinois,

by Stacy Pratt McDermott In 1838, Maria and George Chapman married in Sangamon County, Illinois. During their thirteen-year marriage, they had five children. In 1851, when Maria discovered George's infidelity, she sued him for divorce on the ground of adultery. George Chapman hired a lawyer and denied his wife's charges. The court, however, found him guilty, granted Maria a divorce, and gave her custody of the children. The court also ordered George Chapman to pay $19.90 in court costs. Abraham Lincoln represented Maria Chapman. Lincoln was not a divorce attorney by today's standards. He didn't specialize in divorce cases and settlements. He didn't actively pursue divorce cases, nor did he particularly care to handle them. Many years after Lincoln's death, William H. Herndon, Lincoln's third law partner, wrote that Lincoln hated divorce practice most of all. However, during his twenty-five-year law 6 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE practice, Lincoln handled 115 divorce cases. He and his three law partners— John Todd Stuart, Stephen T. Logan, and Herndon—handled 145 divorce cases between 1836 and 1860. They handled 88 divorce cases in Sangamon County alone, 40 percent of the 220 divorce cases that appeared on the Sangamon County Circuit Court docket during that time. Fifty-four percent of the divorce litigants they represented were women. Of the divorce cases they handled, female plaintiffs brought 63 percent of the cases. The fact that Lincoln and his partners handled such a high percentage of the divorce cases appearing on the Sangamon County Circuit Court docket might suggest the eagerness with which Lincoln's law firms sought to gain business. It may also be indicative of the respect that Lincoln commanded on a personal and professional level. It could mean that fewer lawyers in Sangamon County were engaged in divorce practice or family-related litigation. Whatever the reason, Lincoln took many divorce cases and his contemporaries may have considered him a divorce lawyer.

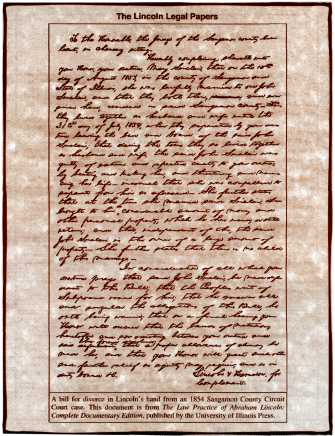

Divorce, Illinois style Lincoln's divorce practice parallels the pattern of all divorce cases in the county and throughout the state. In Lincoln's cases, more women than men filed for divorce. Desertion was the most common of the grounds, cited in 46 percent of all petitions. Petitioners rarely cited the grounds of bigamy, impotence, and felonious conviction. Women were more likely to cite desertion, cruelty, and drunkenness as grounds in their petitions. Male and female plaintiffs cited adultery as grounds in nearly equal proportions. The number of divorce petitions in Illinois increased over time with the largest number appearing in the late 1850s. During Lincoln's law practice, the per capita divorce rate nearly doubled, from an average of 2.10 divorce decrees per 10,000 people in the late 1830s and 1840s to an average of 4.13 divorce decrees per 10,000 people during the 1850s. In 1860, the rate was three divorces per 10,000 people, putting Illinois ahead of the national rate. Family-related cases also became a larger percentage of chancery dockets. Women were taking advantage of their access to divorce in Illinois, indicative of their expanding legal options within the context of their rapidly changing social, legal, and economic roles. Lincoln's practice reflected those changes. Divorce was a viable legal option for antebellum Illinois women. The Illinois legislature provided liberal access to divorce, and many Illinois women chose divorce as a remedy for marital difficulties. By 1850, the number of divorced Americans was rapidly increasing; however, the legal structure of divorce and the occurrence of divorce in Illinois were not typical. Illinois circuit courts liberally enforced divorce laws, and, by 1860, the state was leading the nation in granting divorce decrees. In comparison with other states, the Illinois legislature made divorce more readily available earlier. Illinois gave the circuit courts jurisdiction over divorce in 1819 and completely abandoned the use of divorce by legislative act after 1839. Maryland and Ohio did not relinquish jurisdiction to the lower courts until 1842 and 1843, respectively. Missouri abandoned legislative divorce earlier than Illinois, giving full jurisdiction to the circuits courts in 1818, but the Missouri courts granted a substantially lower percentage of divorce decrees from 1840-1860. Although most antebellum Americans continued to view marriage as a lifetime commitment, many were beginning to recognize that divorce was necessary in some circumstances. As a result, women's access to divorce in many states increased to varying degrees during the period between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Connecticut was leading the way during the 1700s, but by the nineteenth-century, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio were in the forefront of the "easy'' divorce movement. During the period between 1776 and 1850, divorce rates were much higher in western states and territories than in the Northeast and the South. Absolute divorce with the right to remarry, rare in the colonial period, continued to be uncommon or unavailable in some eastern and southern states throughout the antebellum period. Even in states that allowed divorce, like Massachusetts, the legal process was expensive. By comparison, Illinois divorce statutes ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 7  provided for women in dire economic circumstances by exempting them from paying the court costs associated with divorce cases. A changing social climate During the antebellum period, women assumed new economic and social roles that altered and began to transform their familial relationships. Access to divorce certainly helped to redefine "women's legal relationship to the family and provided women with some form of limited legal relief." Legal issues, like divorce and child custody, were becoming more frequent occurrences in local courts across the country. More and more women became participants in the legal system as society addressed new challenges that the expanding roles of women created. Family law was moving to the forefront of legal discourse and legal practice; in states like Illinois, it was becoming a larger part of the chancery docket. For example, county circuit courts throughout Illinois heard increasing numbers of divorce petitions. Rural as well as urban counties reflected this trend. Although the economic, social, and political nature of Illinois counties and the diverse religious, ethnic, and geographical origins of their inhabitants differed significantly, divorce was a common occurrence in courts throughout Illinois. Circuit courts struggled with complex legal family issues associated with the dissolution of marriages. Between 1837 and 1869, 281 couples divorced in Kane County in northern Illinois. The county's proximity to Chicago attracted a migratory population that experienced the familial disruption associated with westward migration. In the Knox County Circuit Court in Galesburg, plaintiffs filed twenty-three divorce suits during the 1840s. This is particularly interesting considering this rural, frontier community had an 1840 population of only 1,210. By comparison, Sangamon County's population in 1840 was 14,716, and by 1850 the county had grown to 19,228 people. Sangamon County was home to the busy state capitol, while Knox County remained remote and bucolic, and Kane County's population was transitory and, therefore, unstable. Despite their differences, however, the three counties had virtually identical rates of successful divorce petitions. The Kane County Circuit Court granted divorce decrees in 76 percent of divorce petitions filed between 1837 and 1869. The Knox County Circuit Court granted divorces in 70 percent of the cases filed there during the 1840s. Sangamon County divorce petitioners obtained decrees 76 percent of the time. The similar circumstances of divorce cases in these three diverse localities reflect the willingness of antebellum Illinois circuit courts to grant divorces. Full divorce was available in the state of Illinois, but the grounds for divorce were at first narrowly defined but increased in number from 1818 to 1845. Illinois law at statehood in 1818 provided for divorce on the grounds of adultery, bigamy, or impotence. In 1824, Illinois legislators added willful desertion and, in 1827, included fraud and extreme and repeated cruelty for two years and habitual drunkenness for two years. Conviction of a felony became an additional ground in 1845. By 1845, the Illinois legislature provided for a relatively liberal number of grounds for divorce, the most significant ground being that of extreme and repeated cruelty. In Illinois, circuit courts granted divorce decrees solely on the ground of cruelty, whereas historically, cruelty could not stand alone, and petitioners could cite it only in combination with another ground. Even given the two-year stipulation, Illinois' provision for cruelty as a viable stand-alone ground for divorce as early as 1827 placed it ahead of most other states. The Lincoln casebook In Lincoln's practice, the Hampton and Waddell cases illustrate the various uses of adultery as a ground in divorce pleading and practice. Both cases shed light on how individuals viewed their options when marital discord arose. The Hampton case is particularly illustrative. After twenty-one years of marriage, Catherine and Samuel Hampton divorced in 1845. Catherine Hampton had accused her husband of drunkenness, desertion, and adultery. She charged that in his drunkenness he had often "failed to provide for her competent subsistence but wasted his means in drinking'' and that he had abandoned her in 1840. At the time she filed for divorce, Catherine Hampton, who was then living in a household with two of her grown sons, also believed that Samuel Hampton was living in a state of adultery with a woman to whom he professed to be married, but legally was not. After hearing the evidence, the court granted Catherine Hampton her divorce. Regardless of the specific ground or grounds that the court recognized to grant a divorce in the Hampton case, Catherine Hampton's legal representation, the law firm of Stephen T. Logan and Abraham Lincoln, wisely included all of the grounds that applied to her case. The bill for divorce filed in this case carefully focused on Samuel Hampton's guilt, while declaring that Catherine Hampton "discharged all the duties of a wife whilst the said Samuel Hampton lived with her." This strategy of emphasizing the innocence of the complainant was common in actions of divorce as the plaintiff's attorneys worked to ensure a divorce decree based on the guilt of the defendant. In an era long before "no-fault" divorces, assigning blame was necessary to meet the statutory requirements for a divorce, and also contributed to determining the amount of alimony and to the resolution of custody issues. The Hampton case depicts two distinct options in dealing with marital difficulties. The remedy for marital difficulties did not necessarily mean legal divorce. Samuel Hampton extricated himself from an unhappy marriage to Catherine Hampton by physically leaving the household. Following that desertion, he entered into another (Continued on Page 16) 8 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE (Continued from Page 8) relationship with a woman and was apparently content to go on with his life regardless of the adulterous and perhaps bigamous situation. For him, legal separation was unnecessary. Unhappy in his marriage to Catherine Hampton, he left and effectively married a new wife. In contrast, Catherine Hampton used a suit for divorce to dissolve her relationship with her husband. For her, legal divorce was apparently necessary in severing the ties to her errant husband. Rebecca Waddell also dealt with an unhappy marriage through extra-legal means. In 1847, at the age of seventeen, Rebecca Johnson married twenty-two-year-old Squire Waddell, a struggling young farmer. They had two children over the next few years. In 1851, Squire Waddell left on a trip to California to make his fortune. When he returned in September 1853, after an absence of at least a year, he discovered that Rebecca Waddell was involved in an adulterous affair with William Welles. In 1853, Squire Waddell retained the law firm of Abraham Lincoln and William H. Herndon and filed for divorce on the ground of adultery. Rebecca Waddell failed to answer the charges. Numerous witnesses then testified to her adulterous activities, and the court granted Squire Waddell a divorce and custody of the children. After the divorce, Rebecca Waddell disappeared from Sangamon County, perhaps having left with her lover. Squire Waddell remained in Sangamon County, prospered as a farmer, and raised his and Rebecca Waddell's two children with his new wife. During Squire Waddell's long absence from the family, the wife he left behind pursued another relationship and did not wait for her husband's return. Squire Waddell claimed that he had left financial support for his family during his absence, but the support may have been insufficient or perhaps loneliness motivated Rebecca Waddell. Many "49er widows" like Rebecca Waddell experienced financial and emotional voids during prolonged absences of husbands. The Waddell case is a gender reversal of the Hampton divorce. In this case, the husband was the one who attached importance to the legal dissolution of the marriage. Squire Waddell did not leave the marriage as Samuel Hampton had. Perhaps his interest in his children kept him from desertion, but certainly Rebecca Waddell's adultery gave him incentive to pursue a legal separation. Although it is possible that Squire Waddell forced his wife into a situation that led to her eventual abandonment of her own children, it appears from the evidence that she chose another man over Squire Waddell and willingly allowed the divorce and relinquished her children to him. Perspectives of marriage and divorce in antebellum America were not necessarily gender specific. Separated but not equal Legal, social, and political discussion on marriage and divorce in antebellum America represented a lifting of past prohibitions on public discourse of private matters and ushered in new attitudes and ideals. As couples began to view marriage within a romantic context, they felt more cheated by unhappy unions than the generation before them had. In turn, divorce became more attractive to people experiencing marital difficulties. One scholar has argued that during the nineteenth century, familial relationships were becoming increasingly companionate rather than patriarchal in nature, which fostered higher marital expectations. The legal, religious, and social implications of marital perceptions and the commitment to the institution of marriage itself did not affect all women or men the same way. However, more and more women and men who experienced unhappy marriages chose legal and extralegal separations. Regardless of their economic circumstances, Illinois women had a variety of reasons for pursuing divorce. Economic, social, religious, and personal considerations no doubt contributed to the way they coped with difficult marriages. However, their gender did not necessarily dictate the course of action they eventually pursued. Neither did social pressures yield predictable choices. Women's motivation to pursue divorce decrees is not immediately obvious in most cases. What is certain, however, is that once they decided to pursue divorce, women in Illinois experienced few legal problems in obtaining a divorce. Access to divorce was more limited in most other states. The most extreme example was in South Carolina where there was no provision for divorce until 1868. Antebellum women in Illinois benefited from those sweeping changes. Although the paternalistic structure of the law of divorce in Illinois prevented equal legal status for women, women did benefit from the willingness of Illinois courts to grant them divorces. Few places in the country allowed women or men as many different reasons for which they could end a marriage than Illinois. Maria Chapman had benefited from liberal divorce provisions when she chose to leave her adulterous husband in 1851. Illinois women of all economic backgrounds had more access to divorce in the antebellum period than ever before. While many circumstances of divorce came with initial embarrassment and shame to the families facing it, the legal process of divorce in Illinois was relatively simple. Many women in Illinois chose that legal remedy and applied it to their unique economic, social, and familial situations. In exercising their legal option of dissolving the bonds of matrimony, women accepted responsibility for themselves and their children, despite the ever-present possibility of great difficulty. And, in some significant way, Lincoln contributed to the efforts of his female clients to remove themselves from difficult marriages and assert their independence in the context of rapidly changing roles and expectations for women in the mid-nineteenth century. Stacy Pratt McDermott is an assistant editor with the Papers of Abraham Lincoln and is the author of two chapters on women and law in Tender Considerations: Women, Family, and law in Abraham Lincoln's Illinois (University of Illinois Press, 2002.) 16 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois Heritage 2003|

|